Tracing an ancestor with an alias

Several recent episodes of The Family Histories Podcast have featured stories of men who had an alias, i.e., an alternative name or identity. In ‘The Marine‘ (series 8 episode 5), Richard Holt told the story of his naval ancestor, who was baptised Matthew Buyrn but later used the name John Dunmore. And in ‘The Secretive‘ (series 9 episode 1), Ron Williams introduced the tantalising tale of his grandfather, Alfred Victor Williams, who also went by Roy Hammond (a story so full of twists and turns that it inspired him to research and write a book in 2024). Genealogist Judith Batchelor (‘Genealogy Jude’) has an excellent 2-part blog about ‘chameleon ancestors‘, looking at some of the reasons why people changed their names or used multiple names, including illegitimacy, nicknames and adoption, or deliberate identity changes, whether for legitimate or nefarious purposes! Whatever the reasons our ancestors had for these choices, it can make it much harder to trace them.

My 2x great grandfather, William Taylor, was a bricklayer, and also a family history ‘brick wall’! A few years ago I finally broke down the wall, when I discovered that he had used more than one name. In this blog I share my research into his origins and alternative identities and uncover the real life story behind a puzzling paper trail. This is also the first of two case studies that look at remarkably similar family history mysteries, but with very different truths behind them …

My maternal grandfather’s mother had an surprisingly grand name for the daughter of a bricklayer: Dorothy Georgina Alexandria Taylor (known as ‘Georgina’). Born in 1905, Georgina’s birth certificate names her parents as William TAYLOR and Edith Matilda Taylor (née LANKFORD). (Edith’s maiden name was occasionally written ‘Langford’).

Despite the information in the birth certificate, William and Edith weren’t actually married. If my great grandmother didn’t know as a child that she was illegitimate, she would certainly have found out when she got married in 1925. Although she signed her name in the register with the surname ‘Taylor’, the vicar who completed the register entered her name as ‘Dorothy Georgina Alexandria Langford (known as Taylor)’. Furthermore, in the space where her father’s name and occupation should have been entered, he wrote ‘Edith Matilda Langford (mother) known as Taylor’. Georgina’s father William Taylor had died the previous year; perhaps his death had brought his unmarried status to light, and the vicar disapproved!

In 1911, aged 6, Georgina (recorded as ‘Dorothy’) appeared on her first census, in Aylesbury, Buckinghamshire, with her parents William Taylor (b. c 1867, Waddesdon), a bricklayer, and Edith Taylor (b. c1878, Hatfield). Georgina was one of five Taylor children, all born in Aylesbury. However, the family also included John, Ada and Elsie Clara HOMAN — aged between 16-21 and all born in Waddesdon — who were also stated to be William Taylor’s children.

William and Edith appeared to be married but the marriage was stated to have lasted 23 years, and as Edith was reported to be 33 years old, this would have meant she’d got married at about the age of 10. She was also reported to have had 8 children, all still living, which matched the number of children in the household, though clearly, the ages of the older children meant they could not have been hers.

The National Archives RG 14/ 7932, Sch 205

It’s not uncommon for the marriage and children columns to have been completed incorrectly, as many people found them confusing, so I thought it likely that the 23 years of marriage and 8 children applied to William, not Edith, and that she was probably only the mother of the Taylor children — starting with Gladys, born in about 1898. But my interest in the Homan children was immediately piqued!

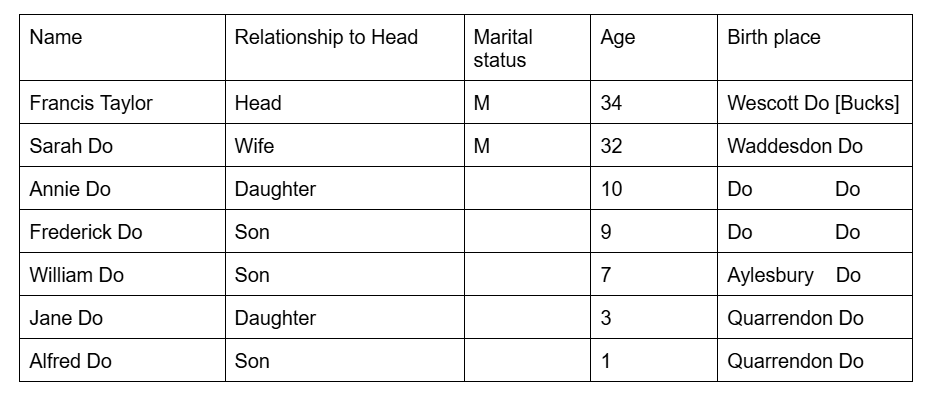

I located the family a decade earlier, in Aylesbury. This time, the family had six children, all with the surname Taylor. However, John, Ada and Clara (2nd, 4th and 5th children — shaded in the transcription below) matched the three children who’d been enumerated with the surname Homan in 1911. Another discrepency was Edith’s age. She had been 33 in 1911 but was said to be 27 in 1901. As I had observed in 1911, the older children’s ages meant it was unlikely that she was the mother of all of them.

The possibility of William having a previous wife who’d died, sadly, wasn’t uncommon. And if she had been a widow who’d already had children with a Mr Homan, it wouldn’t have been unusual for them to adopt their step-father’s surname. But why would they have used ‘Taylor’ in 1901 and ‘Homan’ in 1911?

The National Archives RG 13/1355, Folio 183, Page 32

(Note that their boarder, Victor Lankford, will pop up again later in this blog!)

Going back in time again to 1891, things started to get rather strange. I was unable to find William Taylor but I was able to locate two of his older children: John Homan (who had been John Taylor in 1901 and John Homan in 1911) and Pollie Homan (who had been Polly Taylor in 1901) — shaded in the transcription below. They were living in Waddesdon but their parents’ names were Frederick (an agricultural labourer) and Sarah Homan. They also had an older sister, Lizzie Homan.

The National Archives, RG 12/1147, Folio 76, Page 17

At this stage, before searching for the children’s birth records, my theory was that William and Edith Taylor had adopted the children from Frederick and Sarah Homan, perhaps relations. I found a death for Sarah Ann Homan in Waddesdon, 1896, aged 29, so the idea that some or all of her children were then taken in by another couple seemed plausible.

However, when I researched the Homan children’s births, I found that it wasn’t possible to draw a clear line between them and the Taylors. There were five children who had been given the name Homan in at least one census — Annie Elizabeth (‘Lizzie’), John, Mary (‘Polly’), Ada, and Elsie Clara. All of their births were registered with the mother’s maiden name of ‘Haines’. However, whereas the three oldest were registered at birth with the surname ‘Homan’, Ada (the fourth) was registered with the surname ‘Taylor’ and the fifth child, Clara, was registered with the surname ‘Homan’.

Researching their parents uncovered yet more inconsistencies. I obtained a marriage certificate for Frederick Homan and ‘Ann Hains’ in Aylesbury reg. district in 1887. However, a newspaper announcement of the marriage gave the groom’s name as ‘William Homan’. I also found newspaper articles about the inquest into Sarah Ann’s sudden and untimely death. Although in the 1891 census her husband was Frederick Homan, an Ag Lab, the newspapers in 1896 named her as the wife of ‘William Homan, a bricklayer’.

Digitised image from the British Newspaper Archive

Digitised image from the British Newspaper Archive

The mystery deepened when a search for later evidence of Frederick Homan (e.g. censuses or a death) drew a blank. Likewise, I had been unable to locate a birth record for William Taylor, and searching for him in earlier censuses was also proving a challenge. His ages in later censuses varied, putting his birth between 1865 and 1870.

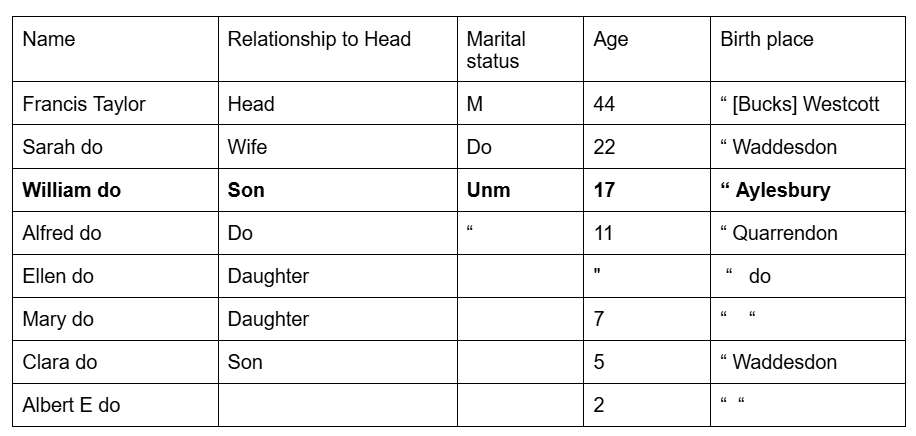

I was unable to find him in 1891 but in 1881 I found a close match in Waddesdon — William Taylor, age 17 (born about 1863). He was living with parents Francis and Sarah Taylor and five younger siblings. Was this my William?

The National Archives, RG 11/1475, Folio 106, Page 18

I was able to find a marriage registration in 1865 for Francis TAYLOR and Sarah HOMAN. Sarah’s maiden name pointed to this being my family. But Francis and Sarah had married two years after William was born, so was he an illegitimate child whose birth was registered with the surname of his mother? I searched birth indexes and found no records for William Homan, but I did find a record for Fred Clark Homan, and his birth certificate showed he had born on 12 June 1863 at Aylesbury Workhouse — the son of Sarah Homan. Bingo. Although censuses from 1891 onwards gave William’s birthplace as Waddesdon, rather than Aylesbury, William grew up in Waddesdon, and may simply have believed that is where he had been born as well.

The middle name, ‘Clark’, suggests that Francis Taylor was not his biological father, and this is supported by DNA evidence that I’ll get to a little later in this blog. I wrote about some potential candidates for his father (with surname Clark) in my blog, ‘Five reasons why ancestors used surnames as middle names‘, but I have also considered the possibility that ‘Fred Clark’ was a mistranscription of ‘Frederick’. ‘Fred’ was usually a nickname rather than a birth name, and there are no examples of him using that shortened form later in life. Furthermore, I have not come across any examples of him using the middle name Clark. It would be interesting to examine the original birth certificate from Buckinghamshire Archives in the future.

By now I was convinced that William Taylor, Frederick Homan, William Homan and Fred Clark Homan were all the same person. It wasn’t at all uncommon for someone born outside of wedlock to use more than one surname, including their mother’s surname, biological father’s surname, and step-father’s surname. So it made sense to me that he used both his birth surname (Homan) and the surname of the man who raised him (Taylor).

But what about the first name? If he had been born with the name Fred (or Frederick) why did he also use the name William? And when did he start to use that name?

The likely answer came from the first census to document William — 1871.

When the 1871 census was taken, Francis and Sarah Taylor lived in Quarrendon, between Waddesdon and Aylesbury. William Taylor’s age (7) and birthplace (Aylesbury) matched the birth for Fred Clark Homan, but confusingly they also had a 9-year-old son called Frederick Taylor, b. Waddesdon. William also had an older sister, Annie Taylor, aged 10. All three of these children were born prior to Francis and Sarah’s marriage in 1865.

The National Archives, RG 10/1414, Folio 77, Page 3

It turned out that Annie (Ann Homan) was another illegitimate child of Sarah Homan. However, Frederick John Taylor was the legitimate son of Francis Taylor, through a previous marriage; Francis had previously been married to Louisa BECK, and she had died just two months before his marriage to Sarah. Francis and Louisa had three children, but two had sadly died earlier that year, and only Frederick had survived.

Therefore, when Francis married Sarah, he was a widower with a child, Frederick Taylor (aged about 3), and Sarah was a single woman with a son, Fred Homan (aged 2), and a daughter, Annie. The 1871 census shows that Annie and Fred took on the Taylor family name*, but Francis already had a son called Frederick (another indicator that Fred Homan was probably not his biological son), and I believe that is why Fred Homan was given a different first name: William. Nevertheless, although he was only a small boy at that time, he didn’t forget his birth name, and continued to use both names at different times in his life.

*It is possible that the census enumerator simply assumed that all children in the household were Taylors, just as they assumed they were all ‘son’ or daughter’ rather than ‘step-son’ or ‘step-daughter’, but since Annie and William continued to use the name Taylor into adulthood, it suggests that they were in effect adopted by their step-father and used his surname from an early age.

DNA Evidence

Despite the many pieces of evidence from birth and marriage records, censuses and newspapers, which together make a strong case, I have not found a single record that definitively states that Frederick Homan and William Taylor were the same man. However, as well as traditional research, DNA offers the potential to provide unequivocal evidence that links me to the Homan family. Sarah Homan was born nearly 200 years ago, five generations before me, and the amount of shared DNA between myself and another descendant of Sarah, or of her siblings, would have to be small. Nevertheless, there are genetic matches to myself and my mother that support my theoretical paper trail!

Most significantly, my mum shares 36 cM with a grandson of Sarah Ellen Taylor — a daughter of Sarah Homan and Frederick Taylor (she is listed as Ellen in the 1881 census transcription above). Sarah Taylor would have been Fred Homan/William Taylor’s half sister, so Ancestry’s prediction that the relationship of this match to my mum is ‘half second cousin 1x removed’ is spot on. My mum is also related to a descendant of a Homan born in Waddesdon the 1700s. And I match a descendant of the wonderfully named Herodias Homan, born in Waddesdon in 1813.

Now that I’ve worked backwards in time, and put the pieces of the jigsaw back into place, I’d like to briefly tell my 2x great grandfather’s life story from beginning to end, this time going beyond mere names and dates.

Fred Homan/William Taylor — a Biography

Fred Clark Homan, born in 1863, was the second child of single mother Sarah Homan, who also had a daughter called Annie. Sarah was the daughter of John Homan, a labourer and a pauper. As a child she lived with her grandparents and worked as a lace maker. Sarah had two sisters, both of whom also had illegitimate children.

Sarah married widower Francis Taylor on Christmas Day 1865, becoming step-mother to his son Frederick Taylor, and by 1871, her son Fred Homan was using the name ‘William Taylor’. (Annie also took on the surname Taylor, but in 1890 she married her cousin, Tom Homan, an illegitimate son of Sarah’s sister, so she became Annie Homan again!)

Fred/William married Sarah Ann Haines in 1887 using the name ‘Frederick Homan’, which suggests that he still considered that his legal name. Their marriage certificate is very unusual, because both of them were illegitimate, so rather than the names and occupations of their two fathers, we have the details of two mothers who were both ‘single women’ when their children were born! If I had ordered a copy of the certificate sooner I would have spotted that Frederick Homan’s mother’s name was ‘Sarah Taylor’ (her married name) but there was no clue to that in the index.

At some point between 1891 and 1896 Fred/William changed occupation from agricultural labourer to bricklayer. I have wondered if this change of career was prompted by the construction of magnificent Waddesdon Manor, which was built on a bare hillside by Baron Ferdinand de Rothschild between 1874 and 1889. In the 1890s Queen Victoria paid a visit and in the following years several new buildings were erected in the town. The church tower was also rebuilt in 1891/2.

In 1895 Fred/William’s mother Sarah died, and the following year, his wife Sarah Ann died suddenly, collapsing on the floor of her home. She had suffered a uterine hemorrhage and had a weak heart. My 2x great grandfather was left a widower with five young children, from 18 months to five years old. From about this time he began to use the name ‘William Taylor’ much more than ‘Frederick Homan’. Perhaps it reflects an increased closeness to his step-father Francis Taylor and his step- and half-siblings at that difficult time.

In the aftermath of this family tragedy, Edith Lankford first came into the household to help look after the children. She would have been just 16-17 years old. Edith came from Hatfield, more than 30 miles away. Her grandfather had been an auctioneer but the family’s fortunes had declined and her father, the youngest of nine, was a pheasant breeder-turned-beerhouse keeper. At some point, she began a relationship with William, and became his commonlore wife. She gave birth to their first child in 1899, ten days after her 20th birthday. By 1901 the family had moved to the nearby, much larger town of Aylesbury, so it might have been easier there for William to let go of the Homan name and also to convince everyone that they were a lawfully married couple. I don’t know why William didn’t marry Edith, but perhaps she was unable to obtain her parents’ consent to marry him (which she would have needed due to her young age), and as time went on, it was far easier to act as if they had always been married. They went on to have nine of their own children (two died in childhood).

The Taylor family was large, and it can’t have been easy for William and Edith to support so many children. Newspapers reveal that they were often in trouble with the authorities. Throughout the Great War William was repeatedly called to Aylesbury Petty Sessions due to his children’s non-attendance at school. It was unfortunate for William that a school attendance officer, Victor Kerr, lived just a few doors away! In 1918, the court heard that one of his children had only attended school on 22 out of 104 days, and that he had been summoned for the same offence on seven previous occasions. He was fined £1. I haven’t found any further charges for non-attendance after 1918, but perhaps that is because the school attendance officer sadly died of war wounds in 1919. In March 1922 Edith was one of several children and adults in trouble for stealing wood. In fact, they had simply found some branches lopped from trees along the canal path. The pompous Chairman said that ‘grown up people should certainly have known that people did not have trees cut down for the purpose of giving the wood away, especially such large pieces.’ Edith was fined 10s for this ‘theft’.

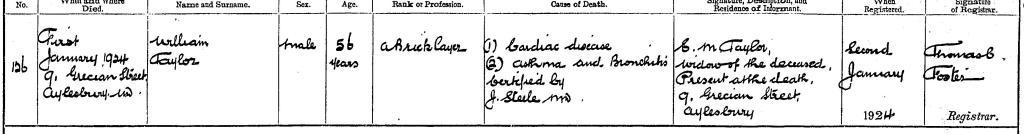

The 1921 census shows that William Taylor was still working as a bricklayer in his late 50s, and living with 7 of his children (in total, he had 14). He died at his home, 9 Grecian Street, Aylesbury, on New Year’s Day 1924, from cardiac disease, asthma and bronchitis. His lung problems were probably caused by his work, which had exposed him to brick dust and other chemicals for about 25 years. William’s ages were rarely consistent in official records (whether due to genuine confusion or evasion), and in typical style, his age at death was given as 56, though he was actually 60. The death certificate names him William Taylor.

Edith was present at his death, and was described on the certificate as his widow. 15 years later, in the 1939 register, she was still ‘Edith Taylor’ but was a ‘single woman’. According to family stories, in the ‘Thirties she had a ‘fancy man’.

For the last 20+ years of his life my great great grandfather had favoured the name William Taylor, but he was clearly comfortable using the name Homan when appropriate. His children with Sarah Ann continued to use the name Homan into adult life, and this led to the unusual 1911 census return, with William having both Homan and Taylor children in the same household. When his Homan children married, they named their father as ‘William Homan, Bricklayer’. The first was Lizzie, who in 1909, rather unconventionally, married her step-mother’s younger brother, Victor Lankford (he’d been boarding with them in the 1901 census), and the last was Elsie, who in 1923 married … a Taylor! (not a relation as far as I can tell, but certainly confusing).

John Homan was the only one of William’s sons with that surname. After marrying in 1916, he had a son, Charles Arthur Homan, born the following year. Tragically, John died of Influenza in 1918, just four days before the end of the War, and the Homan name ended with Charles, who was childless by his death in 1991. My mum, William’s great granddaughter, knew many of her Taylor relatives in her youth, but had never heard the name Homan in connection with her family.

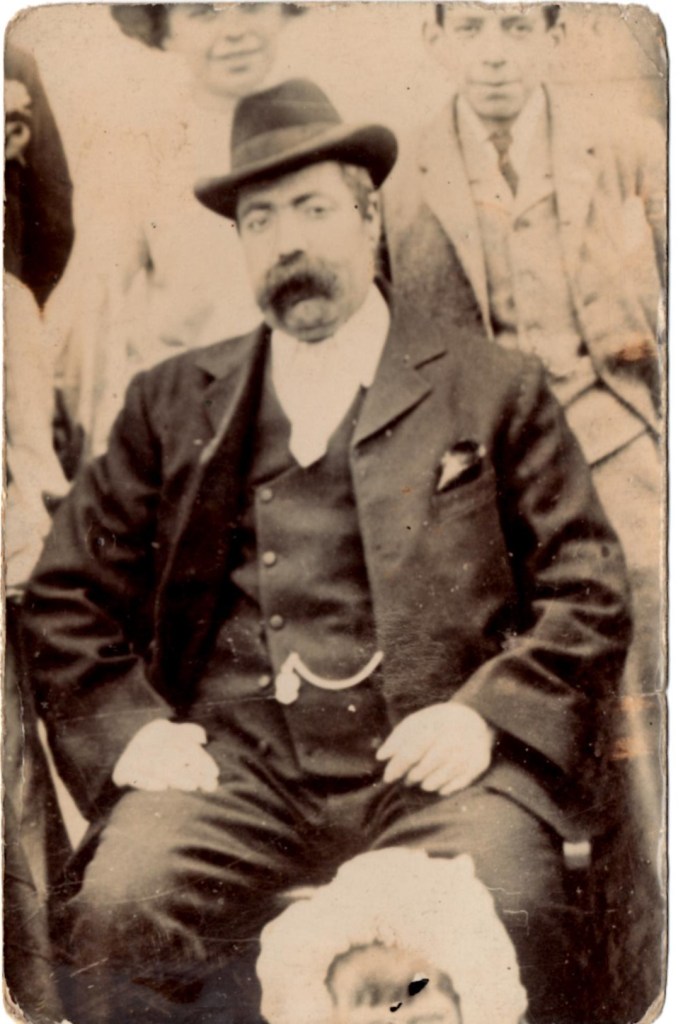

In 2020, I was able to connect with another of William’s descendants (my mum’s second cousin), Jane, who generously shared her excellent research report with me (it was very reassuring to find we had found the same key evidence and come to the same conclusions). Jane also kindly provided me with a photograph of our elusive ancestor, William Taylor aka Frederick Homan; he was a rather solid man wearing a bowler hat and sporting a thick mustache. Presumably he’s surrounded by some of his children. I also have one picture of Edith in my own collection. She lived until 1968, and reached the age of 88.

My sincere thanks to Jane, my second cousin once removed and a great granddaughter of William and Edith, for her research, stories and photograph.

Thank you also to genealogist and civil registration expert Antony Marr for his insights into my great grandmother’s marriage certificate.

CASE 2 Preview

In Case 2 I’ll be sharing the search for my husband’s 2x great grandfather, born around the same time as William Taylor/Frederick Homan. In a bizarre coincidence, the records for this mysterious ancestor also feature the names Frederick and William and two different surnames. Was his name Frederick William CARTER, William CROSS or Frederick Cross? And was this another case of an ancestor with an alias?

Find out more in William and Frederick: Case 2, coming soon …

I really enjoyed this story Clare. There were so many inconsistencies that needed to be ironed out and analysed. I’m always particularly interested in the motivations behind an ancestor’s behaviour.

LikeLike

Thank you, Jude. I agree – as well as establishing the facts it is really interesting to try to understand their possible motivations.

LikeLiked by 1 person