In this blog post I’ll be investigating a story about a man who was reported to have had 30 children, and sharing some methods for finding children who were born in England in the 1800s to early 1900s. If you are looking for a ‘missing’ child or simply to add another generation of offspring to your tree, I hope that you’ll find this helpful.

While researching for a client recently, I discovered a remarkable story about their ancestor, William Wilson (b. 1808). I’d already established that William had married twice, and censuses included the names of 15 children. So, this was already a large family. However, I was taken aback to find a newspaper article from 1866 that announced the birth of William’s 30th child! He’d reportedly had 22 with his first wife and eight with his second. And since I knew of three more children who were born to William after the date of this article, it meant that he might have had 33 children (or more)! I was delighted that my client encouraged me to spend some time searching for his other children in online sources. Could I track down the ‘missing’ boys and girls?

Evidence from the censuses

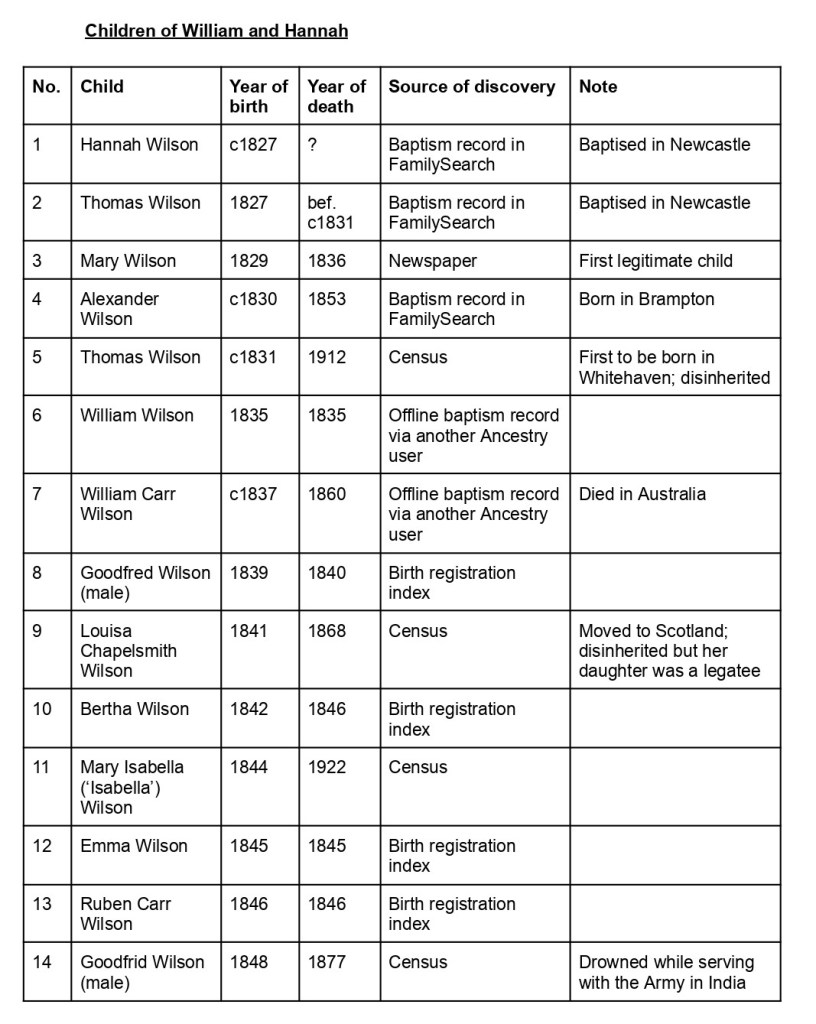

Many of us start to build a new generation of our family tree using census records. And this was my starting point for recording the children of William Wilson with his first wife, Hannah, and second wife, Dinah.

William was born in Whitehaven, Cumberland on 21 April 1808 and he was the second in what would become a four-generation printing/book-selling/stationer’s business in that town. He married Hannah CARR (b. c1807, Hull) in Liverpool on 3 January 1828.

In the 1841 census, we find William living in Whitehaven with Thomas Wilson, age 8 and William Wilson, age 3. Hannah’s whereabouts are unknown. In 1851 William and Hannah were in Whitehaven with Thomas and William (now stated to be William’s sons) and three more children: Luisa [sic] Wilson, Isabella Wilson and Goodfrid Wilson. I noted that Hannah was not only a mother of five but also a straw bonnet maker (she actually had her own shop!)

TIP:

The 1841 census does not record relationships within a household. So additional evidence is needed to be confirm a parent-child relationship. From the 1851 to the 1921 censuses, relationships were recorded between each household member and the head of the household — typically a working, married man. Although his wife was usually the biological mother of any children in the household, this might not be the case; for example, they might be the children of a previous wife. A family historian still needs confirmation from another source.

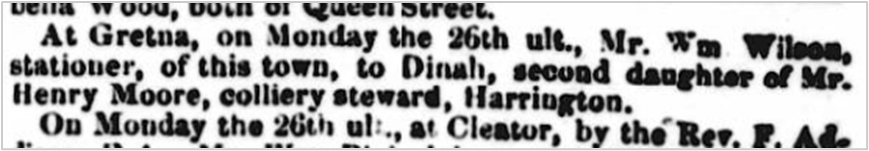

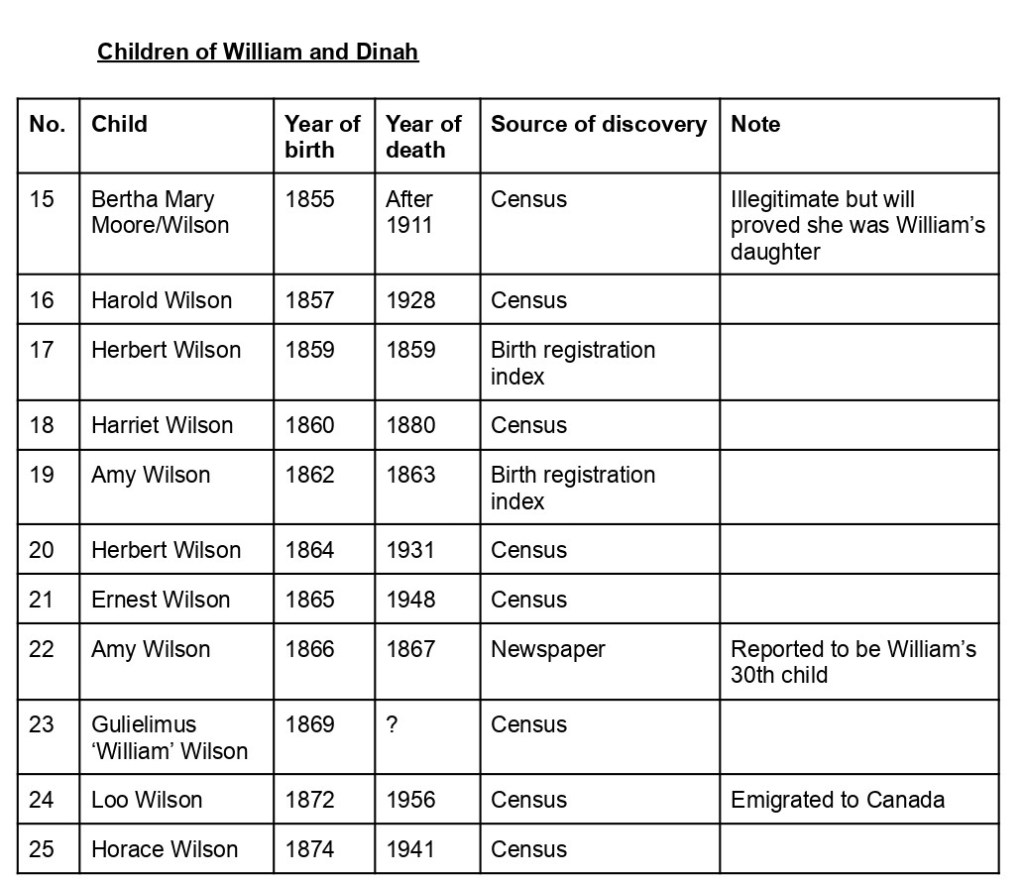

Hannah died on 2 March 1856, and within a few weeks William had remarried to Dinah MOORE (b. c1833, Distington, Cumberland).

In the 1861 census, we find William and Dinah in Distington (next to Whitehaven) with four children. The oldest child, John Moore, is described as ‘wife’s son’ and the rest, Martha Wilson, Harold Wilson and Harriet Wilson, are William’s son and daughters. In 1871, the family, still in Distington, had six children, including a girl called Bertha Wilson, aged 15, and three born since 1861 — Herbert Wilson, Ernest Wilson and the unusually named Gulielimus Wilson. Gulielimus is a Latin form of William, so it seems that William Sr. was already running out of names for his children!

William died on 21 January 1878, and in the 1881 census, Dinah was living with four children, two of whom had been born between the 1871 census and William’s death (Loo Wilson and Horace Wilson).

Getting my ducks in a row

It was tempting to get stuck in right away chasing after the missing children. But I knew that I would be able to do this more efficiently and accurately if I first spent some time gathering more evidence about the 15 children I already knew about, starting with the censuses, and then civil registration (births/deaths) and parish registers (baptisms/burials).

TIP:

Summarising ages and places of birth across the censuses will help to locate birth and baptism records (or, sadly, death/burial records), and makes it easier to spot any discrepencies. For example, if there’s a John aged 1 in 1851, and a John aged 8 in 1861, that might mean that the first John died in about 1852, and another baby was born and given the same name soon afterwards. I only compiled information on William’s children while they were living in his household (or with Dinah after his death) but to be more thorough I could have also inputted census data from his children when they lived elsewhere.

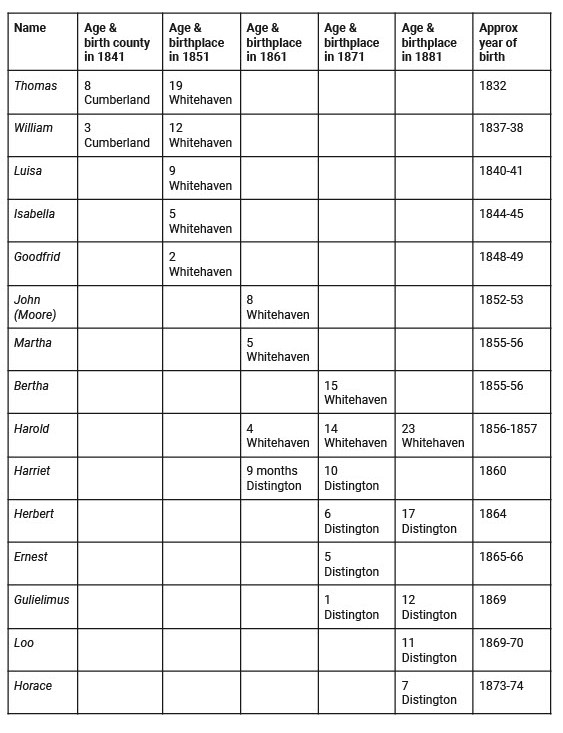

Children of William Wilson living with him in the 1841-1871 censuses, or with his widow in the 1881 census

Observations and questions:

- I noticed that Martha and Bertha appeared in subsequent censuses (Martha only in 1861 and Bertha only in 1871) but they were both estimated to have been born in 1855-56, in Whitehaven. It was probable that they were one and the same child. (and if so, my count of children would decrease, not increase!)

- John Moore had a different surname than William and was said to be his ‘wife’s son’. However, it was possible that he could have been an illegitimate child of William and Dinah.

- Martha/Bertha and Harold could have been born to either mother. Since the newspaper article stated how many children were born to each of William’s wives, I would need to establish who the mother of these children was.

- Loo was said to be 11 in 1881, so she should have been a baby in the 1871 census. It’s possible that she was staying elsewhere when the census was taken, though it would have been unusual for an infant not to be at home with her mother.

- None of these children match the details of William’s 30th child — a daughter whose birth on 11 October 1866 was celebrated in the local news. So, who was she?

- I noted that there were gaps between many of these children long enough for other children to have been born in between.

Tracing birth registrations

Thomas, the oldest child in census records, was born about five years before Civil Registration began in 1837. The next oldest, William, was born just as Civil Registration came into law (b. 1837-8), and his birth might have been registered. Their younger siblings should all have birth registrations. So, I set out to locate birth registrations for as many of them as possible.

TIP:

Two of the best online databases to help with finding birth registrations are the GRO Online Index (gro.gov.uk) and FreeBMD (freebmd.org.uk). Each has its pros and cons. GRO enables you to directly search the official government index to birth registrations. One major advantage is the ability to view and search by maiden name (this is only available in FreeBMD for records from 1911 onwards). However, each search is limited to a time period of just five years and you must select male or female for each search, so it can be time-consuming. In contrast, FreeBMD enables a search of a much broader time period (for an uncommon name, a single search can cover 1837 to the present day) and does not require a sex to be entered. FreeBMD also has better functionality for non-exact and wildcard name searches.

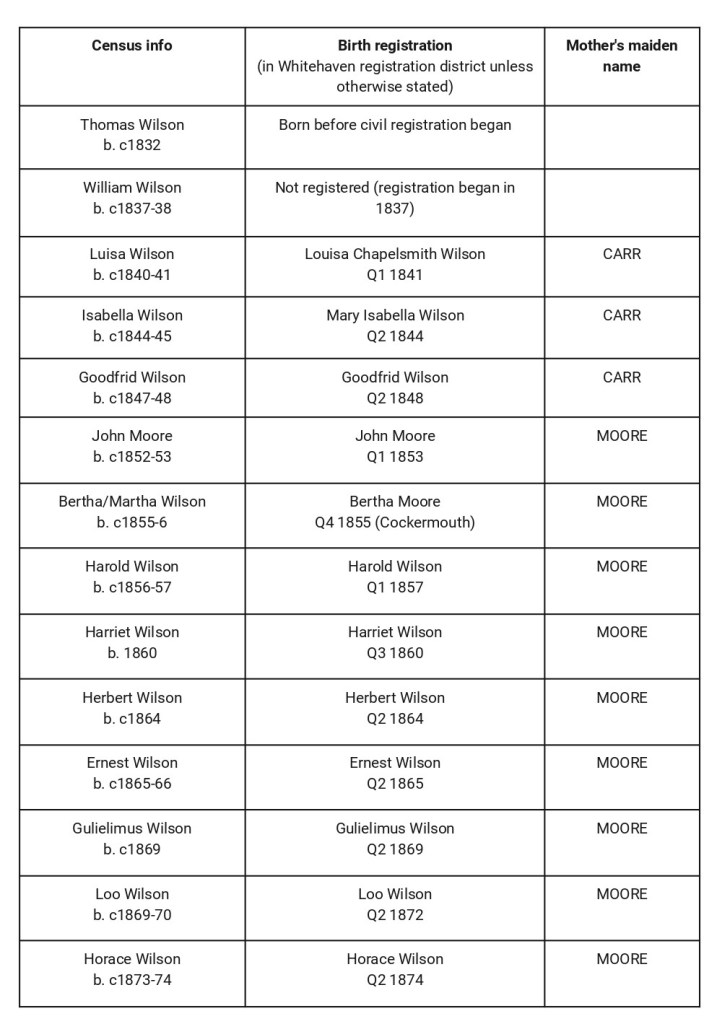

By using the GRO and FreeBMD databases I was able to find birth registrations for 12 of the children listed in censuses:

Observations:

- Loo Wilson’s birth year was later than expected. However, given that she was not listed in the 1871 census, and the lack of any other registrations with her unusual name, I believe that her reported age in the 1881 census was wrong, and have confidence that this is the correct birth registation.

- I found that John Moore was illegitimate, and ordered a digital download of the certificate. Although he was indeed the son of Dinah Moore, no father was named.

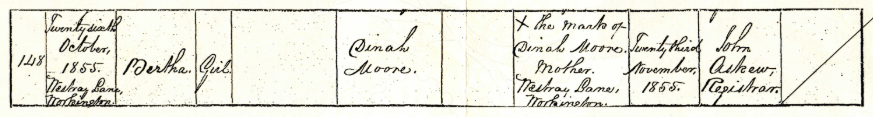

- I was able to confirm that Harold was Dinah’s son, but I couldn’t find a birth for Martha or Bertha Wilson. However, I found a registration for an illegitimate child, Bertha Moore, in Cockermouth (not far from Whitehaven) in Q4 1855 and downloaded the certificate. The mother’s name was Dinah Moore, so I knew that Bertha had been born illegitimately to Dinah Moore prior to her marriage to William Wilson. With no records for a Martha Wilson (or Moore), I also felt confident that her name was Bertha, and that the name ‘Martha’ had been a one-time entry error.

The first additional child is found!

Using the GRO search, I was able to identify William’s 30th child (whose birth was announced in the newspaper). Her name was Amy Wilson, and her birth was registered in Q4 1866. Sadly, Amy died in Q4 1867, which is why she didn’t appear in any censuses.

The search for more children

After building on the details from censuses and the newspaper clipping, I could attribute 13 children to William with confidence. There were still question marks over the paternity of Bertha Moore and John Moore, and about half of William’s children were still unaccounted for. It was time to don my detective’s hat and use a variety of sources to track down as many more of them as possible …

- Birth indexes

As well as using birth indexes to help find the births of known children, we can use them to look for other children born to a particular set of parents. As mentioned above, for children born after 1911, FreeBMD is an excellent resource for a single search for children based on the surname and mother’s maiden name. However, since William Wilson’s children were born in the 1800s, I needed to use the GRO database to search by maiden name, and this meant performing multiple searches for both female and male children over the relevant period of time: from 1837, when civil registration began, until 1879, a year after his death. Since William and Hannah were married nine years before civil registration there was no way to do this search for that first phase of their marriage.

TIP:

The GRO search form requires you to enter a single year between 1837 and 2022 (excluding 1935-1983) and you can choose to include matches for up to two years before and two years after that year. So, each search covers five years. That means that if you’re searching over a longer period, you can skip forward or back five years in each search. For example, a search of 1885 +/- 2 years covers 1883-1887. The next search of 1890 +/- 2 covers the years 1888-1892.

For a common combination of surname and mother’s maiden name, narrow the search by selecting the county or registration district. To allow for spelling variations, especially with names that were likely to be mispelled, try searching with phonetically similar or similar sounding names, or searching with the surname and registration district but no mother’s maiden name.

A thorough search of the GRO birth index added six more Wilson children to my list. A search of the death index found that all had died as infants before the 1841 census or between later censuses:

- Goodfred Wilson b. Q2 1839 d. Q1 1840 (MMN CARR)

- Bertha Wilson b. Q2 1842 d. Q1 1846 (MMN CARR)

- Emma Wilson b. Q3 1845 d. Q4 1845 (MMN CARR)

- Ruben Carr Wilson b. Q4 1846 d. Q4 1846 (MMN CARR)

- Herbert Wilson b. Q1 1859 d. Q4 1859 (MMN MOORE)

- Amy Wilson b. Q2 1862 d. Q1 1863 (MMN MOORE)

(all births and deaths registered in Whitehaven)

Unfortunately, extremely high child mortality in the 1800s mean that many of us researching our family history in this period will find evidence for children who lived for just a short time between censuses. The child mortality rate dropped by a half from 1800 to 1900, but it was still all too common into the 20th century.

TIP:

For those of us researching into the Edwardian era, the 1911 census provides a unique source of information on families; it asks married women how many children had been born alive to that marriage, and how many of those children were still living, or had died. If the mother was an older woman, she may have had adult children who had died, but in a younger family, this can provide a vital clue to look for missing children from your tree.

2. Baptism and burial registers

Unfortunately, there are no digitised or indexed parish registers for Whitehaven available online. The registers are held at Whitehaven Archive and Local Studies Centre, and I was unable to travel to see them. However, thanks to an Ancestry user researching the Wilsons, who is local to Whitehaven, I know of another child baptised there to William and Hannah prior to civil registration and the censuses: William Wilson, bp. 1 Feb 1835; the National Burial Index showed that he was buried as in infant in Whitehaven on 25 Feb 1835.

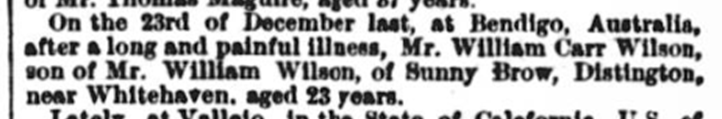

Nearly three years after baby William’s death, William and Hannah baptised another William at Whitehaven: William Carr Wilson, on 10 December 1837. This is the William who appeared on the 1841 and 1851 censuses (and thanks to his middle name I know that he died in Bendigo, Australia in 1860, possibly while pursuing the gold rush that began there in 1851).

If I was able to extend my research, I would have gone to the Whitehaven Archives to peruse the baptism and burial registers for other potential children.

3. Other databases

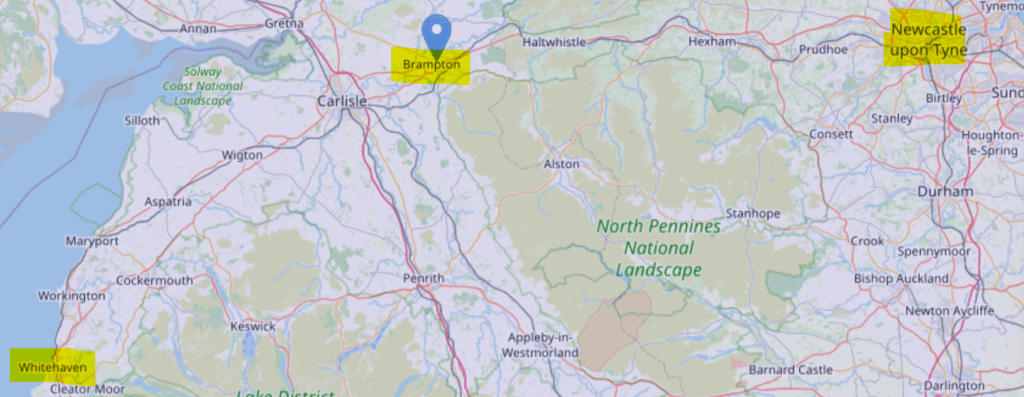

If you’re like me, you have a preferred primary commercial database that you usually turn to first for basic searches. However, it’s always a good idea to search in multiple free and subscription-based databases, since many contain unique data. FreeReg and FamilySearch are both free databases that include a wealth of English parish register entries. In this case, FreeReg didn’t produce any more children, but in FamilySearch, I found a baptism record for Alexander Wilson, son of William and Hannah, at Brampton, Cumberland, 14 September 1830. Brampton is nearly 50 miles from Whitehaven. However, other evidence confirmed that this was the same family. Alexander was living in Whitehaven with his Wilson grandparents in 1841 and 1851. In his teens he joined the family bookselling business, but he died from consumption at the age of 20 in 1853. His death was announced in newspapers, where he was stated to be the ‘son of Mr Wilson of King Street, Whitehaven’.

I was also surprised that my search results included indexed records of two baptisms that took place on same day in Newcastle. Hannah Wilson and Thomas Wilson were christened on 9 April 1827 to William Wilson and Hannah Carr. Perhaps they were twins. Newcastle may sound too far, but I knew that William and Hannah had married in Liverpool and that Hannah came from Hull, so this family certainly moved around considerably. Moreover, from looking at a map I could see that Brampton, where they had baptised Alexander, was almost exactly halfway between Whitehaven and Newcastle. It also made sense that William would name his first child Thomas, since that was his father’s name.

So, it is perfectly plausible that William and Hannah baptised two children in Newcastle prior to their marriage in January 1828. It might be that they lived in Brampton but chose to baptise their children at a distance due to being unmarried. Or they may have been living in Newcastle in the late 1820s; if so, what took William there? William’s father Thomas was a bookseller, and later in life William followed in his footsteps. But he started out as a printer, and by the time of his marriage, when he was about 21, he was a printer residing in Liverpool. Perhaps prior to working in Liverpool, he had served an apprenticeship in Newcastle. It would be interesting to look at some trade directories or at Newcastle’s freeman or guild records..

I noted that one of the Newcastle baptism records was catalogued as non-conformist; since the two children were baptised on the same day it is very likely that both were baptised in the same non-conformist chapel. Frustratingly, the transcribed records did not state the name of the place of worship where the baptisms took place. In 1827, Newcastle had a great many chapels of many denominations, including Presbyterian, Baptist, Methodist, Unitarian, Swedenborgian, Congregational and Independent, as well as a Quaker meeting house. Since some non-conformist baptism registers provide rich family history information, a trawl through surviving baptism registers, as well as other records, such as minutes, would be worthwhile (but was not possible in this project).

TIP:

Although it’s a commonly held trope that people in the past rarely left their village, it’s also well-known that the industrial revolution triggered mass migration across the British Isles, especially to larger towns and cities. Building comprehensive timelines, creating visual maps of our ancestors’ known whereabouts, and studying trades in different towns and regions can help us to understand the journeys they might have taken. And in turn, this can help verify possible children born in unexpected places.

4. Newspapers

Newspapers are a great source for simple announcements of births, marriages and deaths, but they can also lead to some fascinating discoveries, just like the article about William’s 30th child that set me off on this research project. Earlier in this blog we looked at whether Bertha Moore, who was described in censuses as Dinah’s daughter, was also William’s daughter. I had found a birth registration in Cockermouth and was able to confirm that this was the right child. Bertha had been baptised in Workington on 11 November 1855. But both her birth and baptism records only named her mother, Dinah Moore. I considered ordering her marriage certificate, but since she had grown up in William’s home, it was likely she would name him as her father even if she wasn’t his biological daughter. I wasn’t expecting to be able to confirm her paternity, so I was surprised when the truth about Bertha was uncovered as a result of a family scandal that made it into the local news.

After Hannah’s death from tuberculosis in March 1856, William had rapidly remarried to Dinah Moore, a miner’s daughter and agricultural labourer, who was 25 years his junior. They married at Gretna Green in May, and a week later their marriage was announced in the Whitehaven Advertiser.

Their decision to go to Gretna Green points to disapproval from their family or community, and three weeks later, the same newspaper that had announced the marriage reported on ‘A Family Fracas’. Two of William’s oldest children, Thomas and Louisa, by then older than their new step-mother, had strongly objected to the marriage, and the disagreement had led to a violent physical altercation between the adult children and their father. Crucially, the report stated that ‘his present wife had one child by him before his first wife died.’ Given that Bertha had been born in late 1855, a few months before Hannah’s death, everything fitted. And then finally, William’s will (see below) removed the last element of doubt; I could add one Moore child (😉), Bertha Moore/Wilson, to our list.

I had also hoped to find an obituary to William printed in newspapers, as surely, I thought, that would have provided some details of his life and a final count of his children. However, the British Newspaper Archives was missing the relevant issues of the Cumberland Pacquet for 1878, so I contacted Cumbria Archives. They consulted the papers on my behalf and let me know that a notice of William’s death did appear in that paper and in the Whitehaven News, but unfortunately, it only included his name, age and abode.

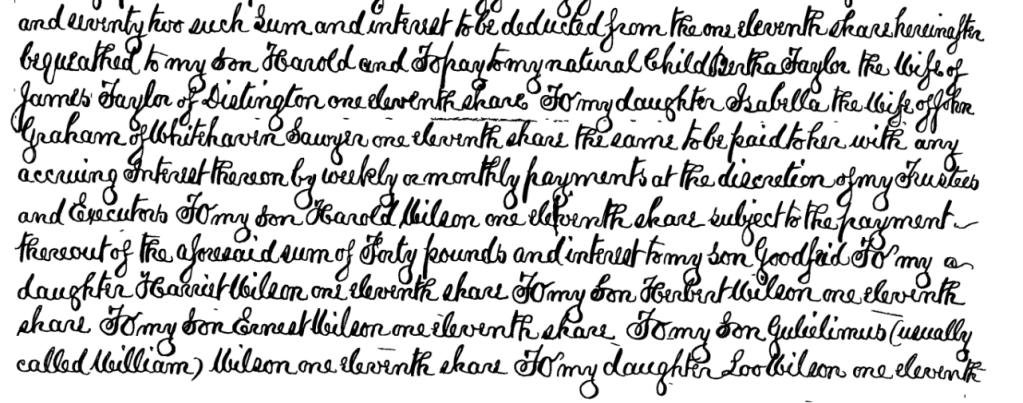

5. Wills

A will made after civil registration began in 1837 is unlikely to reveal previously unknown legitimate children. However, William’s will of 1876 did confirm that he was the father of Bertha. An equal share of his estate, split 11 ways, was to go to his ‘”natural daughter” [i.e., illegitimate daughter] Bertha Taylor, the wife of James Taylor of Distington’. Furthermore, although Bertha was not a beneficiary of his mother’s will, he directed that the other children arrange for her to receive an equal share.

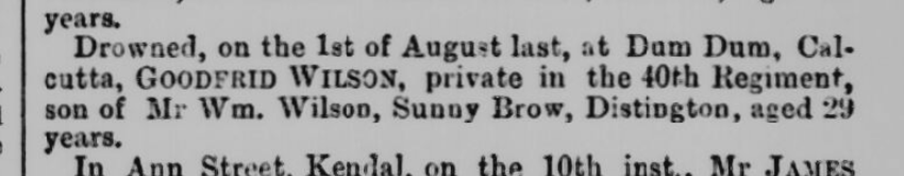

William’s will also provided useful information about nine of his surviving children who were his legatees, as well as two glaring omissions: Thomas and Louisa, who had fought with him after his re-marriage (though Louisa’s daughter was a beneficiary). It was poignant to note that a codicil mentioning his son Goodfrid was written without the knowledge that Goodfrid, a Private in the 40th Regiment, had actually drowned in India just nine days earlier.

6. Other family trees

We should always carry out as much of our own independent research as possible, finding and recording evidence from primary sources. However, occasionally, another researcher might have some knowledge or records that can be illuminating.

I’ve mentioned above that I was grateful to another researcher for the work he had done searching for William’s children in the parish registers of St Nicholas’s, Whitehaven. This same Ancestry user also had evidence of another child, Mary Wilson, who died in Whitehaven on 20 June 1836. Although he could not recall the source of this information, a search for the name in the British Newspaper Archive led me to a notice of her death in the Cumberland Pacquet, and Ware’s Whitehaven Advertiser. She was the ‘eldest daughter of Mr William Wilson, printer’ and sadly died at the age of 7. I had not found this in previous newspaper searches (based on the father’s name, surname and place), and without browsing the trees of other researchers interested in the same family, I would not have known about Mary’s existence.

After hunting for children in birth indexes, baptism registers, newspapers and wills, I had been able to identify 13 further children — 10 more born to Hannah (including the two illegitimate children baptised in Newcastle that were very likely to be hers) and three to Dinah (including her illegitimate daughter Bertha). Of the 22 children that Hannah was said to have had, I had found 14. And I had found all of Dinah’s eight, in addition to the three she had after the newspaper report. In total, I have been able to find 25 children born to William Wilson, spanning nearly 50 years.

Where were the other children?

My search was not comprehensive — there are other sources I could have looked at, many of which are mentioned above — so it’s certainly possible that there is evidence of other children of William Wilson and his two wives that I have not been able to find.

It’s also possible that the news story that started this project is wrong. Perhaps William was simply exaggerating his virility!

However, it is most likely that the missing children were not recorded in official records because they didn’t live long enough, or at all.

The newspaper article about William’s 30 children stated that they had ‘been born’ or that his wife ‘bore’ them. However, it does not say that all of the children were born alive, or at full term. The average total fertility rate for a woman in the UK between 1825 and 1875 ranged from 4.76 to 5.52. But that underrepresents the actual figures for pregnancy/birth. As Dr Sophie Kay says in her excellent and very personal blog, The pitter patter of ghostly feet, ‘officially speaking, stillbirths generally represent a partial blind spot in the official record until we reach 1927 in England and Wales, when the civil registration of stillborn children was legally enacted.’ Sophie shares testimonies of mothers of large families in the early 20th century who had also experienced pregnancy loss; it is a reminder that even in large families, or perhaps especially in large families, official records only tell us part of the story.

We family historians can attest that many women of child-bearing age in the 19th century were giving birth about every other year. Dinah managed to have 11 children in 19 years; that’s one birth about every 20 months. There were no obvious gaps between her children before William’s 30th child was announced. Only in her later years did the frequency of births go down slightly. In the early years of Hannah’s marriage there was perhaps space for one more child to have been born (c1833). But between 1835 and 1848, Hannah produced nine children — about one every 15 months! It left little room for additional pregnancies, although given that her first children might have been twins, multiple births in which only one baby survived are a possibility. Hannah’s last known child was born in 1850, when she was about 42, and for the last six years of her life after that, no births were registered. If she did get pregnant during that time, it’s pertinent to note that in addition to the increased risk from her age, she was in poor health, and tuberculosis has been linked to increased rates of miscarriage.

If some of the children that William was including in his count had been stillborn, it means, poignantly, that those children had not been forgotten. They counted. Sadly, a great many of his documented children also died as infants, children or young adults. It’s quite shocking that only two of Hannah’s 14 known children lived past the age of 30.

Although I’ve used the story of William’s 30+ children to illustrate some techniques for finding them in records, and have focused on him as the prolific father, I’d like to end by acknowledging the strength of the two women who brought all of these babies into the world. Pregnant for most of their adult lives, they raised houses-full of children while supplementing the household income, battling disease, appeasing aggrieved family members and enduring substantial loss.

So, here’s to Hannah and Dinah, two extraordinary mothers.

Wow! It’s amazing that you were able to find evidence of 25 children. William’s mobility, the children born illegitimately and the sheer number of his offspring made this a complex task. Your approach was meticulous and it was a great idea to construct a table. Lots of brilliant ideas about sources too. It’s incredible to think about the women who spent so many years in childbearing. The loss of so many babies and small children must have so hard.

LikeLike

You left out one of the major sources for finding “Lost Children”

Family Bibles and other similar records created by the family themselves.

see:

https://yanceyfamilygenealogy.org/Saving_The_Lost_Children2.pdf

see also:

https://yanceyfamilygenealogy.org/family_bible_index.htm

LikeLike

Hi Dennis. I knew from the beginning that my client didn’t have any personal records from that side of their family so I didn’t mention it as a possible source. But a family Bible is a wonderful thing to have. One existed for my mother’s family but sadly it was sold by auction after a cousin died many years ago. I wasn’t aware that a database existed and think that’s a fantastic resource. Hopefully over time more people will contribute from the UK as well. Thanks for sharing.

LikeLike

The Bible Index includes worldwide resources – including the UK

see also: https://yanceyfamilygenealogy.org/family_bible_index_Locations_OTHER.htm

LikeLike