Over the past several years, around the time of Remembrance Day, I’ve shared the stories of six men in my family who served in WW1. This year I would like to tell you about another brave soldier, Percy Kirk, but this is also a story about his resilient and devoted wife, Hannah, and the impact that the Great War had on both of them. I’ll also be looking at Pals battalions, zeppelin air raids in Hull, and the close bonds that formed between siblings in two ‘blended’ families.

Percy Kirk, my husband’s great grandfather, was born in Hull on 3 May 1887. His father Henry had steady work for many years as a railway guard, but once Percy had completed his education at 12, he began contributing to the household income, working as an errand boy. At the age of about 21, Percy had attempted to join the Military, but was rejected for unknown reasons. However, two years later, the 1911 census shows us that Percy, aged 23, was the manager of a fruit shop.

The 1911 census also gives us a snapshot of a ‘blended’ family. Percy had two sisters and five brothers. However, his mother, Mary Ann, had died when he was 15, and three years later, his father had remarried to Hannah. Percy’s step-mother had been married and widowed twice before — she had a daughter by her first husband and three sons by her second husband. In 1911, Percy lived with three of his Kirk siblings as well as his three step-brothers, who had the surname Jackson.

When war broke out in August 1914, Percy, 27, was a ‘Colour Works Labourer’ at Blundell Spence and Co, a Hull paint manufacturer. On 7 September, just a month and three days after Britain declared war on Germany, Percy was one of thousands of Hull men who rushed to volunteer for the new Hull ‘Pals’ battalions. Percy enlisted as a Private in the East Yorkshire Regiment (service number 11/30). He was to serve in the 11th (Service) Battalion (2nd Hull), commonly known as the ‘Hull Tradesmen’s battalion’.’

Pals battalions were conceived by General Sir Henry Rawlinson, who suggested that men were more likely to enlist if they knew they would be fighting alongside their friends and brothers. At the outbreak of war, Percy’s family included six young men — three Kirks and three Jacksons. All but one, 17-year-old Dick Jackson, were of eligible age to sign up. By 1917 four of his brothers/step-brothers were serving, and at least one was in the same battalion, so it’s probable that several volunteered together.

Despite enlisting early, Percy wasn’t deployed overseas until late 1915. And by the time he left England, he was married.

Percy Kirk and Hannah Thacker were probably sweethearts before war broke out in August 1914. Like Percy, Hannah was born and raised in Hull, though her parents John (a brassfinisher and later, hotel porter) and Elizabeth came from Birmingham. It is a marvel that Hannah survived infancy — within three weeks before she was born, on 5 May 1891, four of her siblings died of infectious diseases. But survive she did, and in 1911, aged 19, she was a domestic servant just around the corner from Percy’s home. Hannah’s employer was a fruit broker, and it’s likely that he sold fruit to Percy.

This elegant picture of Hannah possibly dates to her engagement, although the style of her hair and clothing points to around 1910, perhaps when she first entered domestic service.

Percy and Hannah were married at St Luke’s, Hull on 29 August 1915. A few weeks earlier, at midnight on 5 June, a German zeppelin carried out the first air raid over Hull. Today we are all too familiar with the idea of air attacks and ‘The Blitz’ but in 1915 the sheer sight of a massive zeppelin in the sky must have been truly terrifying. As the zeppelin approached the city, it became silent and motionless, before dropping 2,762 lbs of high explosives and incendiaries.1 25 civilians were killed. Many of the Hull Pals were home on leave at the time, so perhaps Hannah and Percy experienced the attack together. One Private from the 12th Bn. who was on leave in Hull that night was so traumatised by the air raid that he was discharged from service and admitted to an asylum, where he died in 1918.2

Four pages of Percy’s service record have survived but they are in poor condition, providing only some scant details of his service, his eye colour (grey) and hair colour (brown). Thankfully, David Bilton’s book, Hull Pals (Pen & Sword, 1999), provides a fantastically detailed account of the entire war for the Hull Brigade — 10th (‘Commercial’), 11th (‘Tradesmen’), 12th (‘Sportsmen’) and 13th (‘T’others’!).

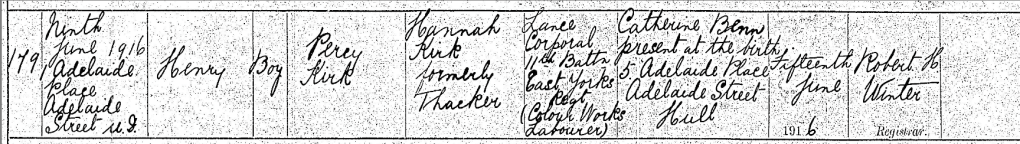

After many months of training, in August of 1915 the Hull Pals were assigned to the 31st Division: 92 Infantry Brigade. On 3 December, Percy was appointed a Lance Corporal, which meant that he would oversee some other Privates. The 2nd Hulls set sail on 10 December and arrived at Malta nine days later. Conditions on board were cramped, especially as the men were sharing space with horses and mules. Food was poor and the men’s seasickness was compounded by the side effects from cholera vaccinations. At Valletta, Malta, they learned that their destination was Egypt, and their task to defend the Suez Canal. They arrived at Port Said on Christmas Eve. Their time in Egypt was monotonous and often unpleasant — with sandstorms, dysentery and water shortages — but they saw very little action. However, the posting to Egypt was short-lived; just three months later, in March 1916, the Hull Pals were transferred to France.

Meanwhile, back home, Hannah was starting married life without her husband. The address Percy gave for his wife in his service records was just a few doors away from where Hannah’s parents had lived in 1911, so she may have been living with them as a newlywed. She would have needed practical and financial support, because by the time that Percy arrived in France, she was six months pregnant. And the day before he disembarked at Marseilles and boarded a train north to the Western Front, Hull was hit by a second air raid, with at least ten high explosive bombs and up to 50 incendiary bombs falling on the city. Lighting restrictions imposed for safety made Hull ‘the darkest city in England’.3 Many streets in Hull had ‘street shrines’ with a roll of honour and lists of those who had died.4, which must have provided a constant reminder to Hannah of the dangers Percy faced, especially after 28 March, when, having been issued an uncomfortably heavy helmet and a gas mask, Percy descended into the trenches for the first time, at Auchonvillers in the Somme.

On 6 June Hannah gave birth to a son, Henry, who would be known throughout his life as Harry — my husband’s grandfather. Less than a month later, Percy found himself in one of the most lethal offensives of the Great War — the Battle of the Somme. However, all of the Hulls Pals battalions were kept in reserve on the first day of the Battle of Albert, on which 57,470 British servicemen lost their lives. Air raids continued in Hull. On 8-9 August, when Harry was two months old, the ‘Selby Street Raid’ killed a dozen people including two mothers and their daughters and a three-year-old boy. Many people from Hull spent the night in fields and parks.

Over the following months, I am sure that Hannah would have written to Percy to tell him about their baby son and about life back home, including the air raids. In return, he sent a postcard portrait home from ‘Somewhere in France’ (left below). Percy is the soldier on the right, and I suspect that the seated soldier is his younger brother Fred Kirk. I am sure that Percy would have been proud to tell Hannah that on 13 November he was made a Corporal, commanding a section of soldiers. However, he may not have mentioned that on the same day, the 11th Bn. commenced fighting in the Battle of the Ancre. It’s possible that Percy was injured during his service; the Kirk family photo album contains a mysterious image of a military hospital as well as another photograph of a soldier with a rifle, who may or may not be Percy.

In early April, the division moved to Arras. In the early hours of 3 May 1917, after leaving German trenches they had been living in, they participated in the ‘Third Battle of the Scarpe’, specifically in the Battle of Oppy Wood. The attempt to capture this one-acre piece of woodland was primarily a diversionary tactic. The wood was elaborately fortified and defended by experienced German troops. Worse still, a full moon and ‘very lights’ (extremely bright search lights) made the men extremely vulnerable as they advanced up a slope towards the wood. Once in the wood, they became entangled with barbed wire and found themselves under constant machine gun fire.

The 11th battalion diaries (National Archives WO/95/2357) paint a vivid and chilling picture of the events:

To get to the assembly line positions Coys had to go over the top of a rise within 100 yds of the Bosch with a moon low in the sky behind them. Also while they were assembling German VERY LIGHTS were falling on the W. side of them. Therefore it was not to be surprised at that at 1-40 AM the Germans started an intense barrage on the Battalion which never really stopped all day. … Zero hour was at 3-45 AM. At this hour the Battalion had been lying out in the open under a very heavy hostile barrage for 2 hours 5 minutes. … Our own barrage started at 3-45 AM advancing at the rate of 100 yds in four minutes and the Battalion followed 50 yds in rear of the Barrage. It was dark, the smoke and dust caused by our barrage, and the hostile barrage, also the fact that we were advancing on a dark wood made it impossible to see when our barrage lifted off the German trench. Consequently the Hun had time to get his Machine Guns up. Machine Guns were firing from within the wood from trees, as well as from the front trench, nevertheless the men went forward, attacked and were repulsed. Officers and NCO’s reformed their men in “NO MAN’S LAND” under terrific fire and attacked again, and again were repulsed. Some even attacked a third time, some isolated parties got through the wood to OPPY VILLAGE and were reported there by aeroplanes at 6 AM. These men must have been cut off and surrounded later. The Battalion was now so scattered and casualties had been so heavy that it was decided to consolidate the only assembly trench we had when the Battle started. The casualties were as follows:-

[list of 12 Captains/Lieutenants missing/wounded/killed]

9 O.R. killed

150 O.R. wounded

98 O.R. missing

The Oppy Wood battle was the deadliest for the 11th Bn. in the entire war, with 56 men killed at Oppy Wood that day (200 from the combined Pals battalions). One of them was Hull FC rugby league player Jack Harrison, who was posthumously awarded the Victoria Cross.

Another was Percy Kirk. He had been killed in action on his 30th birthday.

A newspaper article in the Hull Daily Mail reported Percy’s death, and provided an account of his final courageous actions provided by his step-brother Albert Jackson, who was perhaps serving with him. Percy was making his way to safety when he had heard a pal shouting for help, and had gone to his assistance, ‘and then it was that he met his death’.

The report also states that Percy was ‘buried on the birthday of the widow’ — Hannah turned 25 two days after Percy’s death. However, I am not convinced that Percy had a burial, as he has no individual grave marker; he is commemorated at the Arras Memorial, Bays 4&5. Percy is also remembered in Hull on the city’s war memorial and on a brass plaque for employees of Blundell Spence and Co Ltd. Other memorials include one at the site of the battle, and The Battle of Oppy Wood, a living war memorial of 18,000 trees at Cottingham, just outside Hull.

I took some comfort in reading that Percy had ‘recently been home on leave’; it meant that he must have met his baby son Harry, who was just 11 months old when Percy was killed. I hope this gave Hannah some comfort too.

In the same issue of the Hull Daily Mail, in the Roll of Honour, Percy’s ‘sorrowing wife and baby’ and many of his siblings shared their tributes to this ‘hero brave loving and kind’. He was clearly much loved by his extended family, and although he had been 18 when his father remarried — almost an adult — I noted that there was no distinction in these tributes between his biological and step-siblings. All of the young men, most of whom had a shared bond of fighting for their country, were his brothers.

On 12 April 1918, one of those brothers, Private John William ‘Jack’ Jackson, was killed in the Battle of Estaire or Hazebrouck. Jack also served in the Hull Tradesmen’s battalion (service number 11/419). His death was especially tragic as he had got married just a few weeks before. Jack Jackson is remembered at Ploegsteert Memorial, Belgium.

As far as I know, all of Percy and Jack’s other brothers came home. However, about half of the Hulls Pals (2000 men) never returned. Many families, villages and neighbourhoods across Britain suffered catastrophic losses due to Pals battalions, as so many that enlisted and fought together also died together (and many of those who survived had life-changing injuries). After the Battle of the Somme, no more Pals battalions were raised.

The last air raid in Hull took place in March 1918. There had been more than 50 warnings and at least eight attacks on the city, with 160 casualties, and extensive damage. But as the war finally came to an end, Hull came under attack from yet another enemy: ‘Spanish flu’, which had reached the city in about June 1918. Within a year, 1,261 died, nearly half of them in October and November.5 Health officials carried out door-to-door visits to young mothers in the poorest areas of the city. Was Hannah Kirk among them?

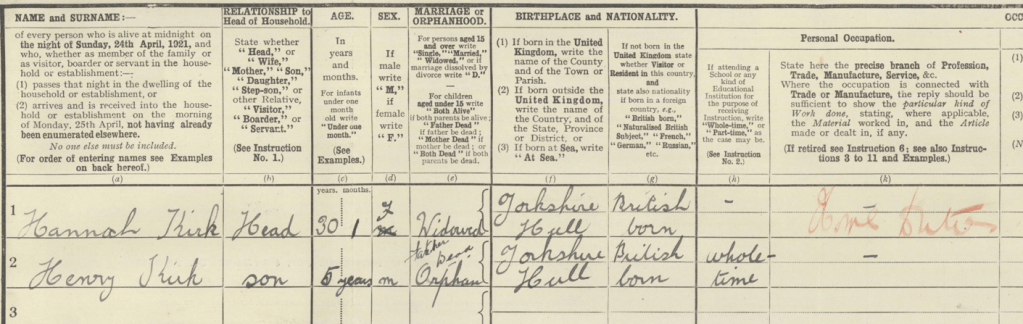

It is difficult to know how Hannah managed financially. Between November 1917 and December 1919, the Register of Soldier’s Effects for Percy shows that she received three payments, including the widows’ War Gratuity, totalling about £19 — £1100 today. It was a meagre amount for the loss of her husband and the father of her child. The 1921 census shows Hannah and five-year-old Harry at Mayo Terrace, Stanley Street in Hull. Harry is described as an orphan. Hannah had no paid employment, so perhaps she was being supported by family.

For ten years after Percy’s death, on the anniversary of his death (and his birthday), Hannah placed memorials in the Hull Daily Mail. When I discovered that she had honoured him in that way for so long, I was very moved. The notices even continued for a year after she remarried in 1926. As she wrote in the 1921 memorial, ‘Love and remembrance last forever.’

One of many annual messages ‘In Memoriam’: Hull Daily Mail, 3 May 1920; British Newspaper Archive

Hannah’s second husband, Jesse Callis, was a widower with three children. He was a deep sea fisherman who’d served with the Royal Navy in the war (Hull’s fishing fleets were commandeered by the navy to become mine sweepers). Hannah and Jesse went on to have two children of their own. So, just like Percy, Harry Kirk grew up in a mixed family, with half-siblings and step-siblings (a fact that was unknown to his own son until he met some of the brothers at Harry’s funeral in 1998). We tend to think of blended families as modern phenomena, but Percy and Harry’s families show that families in the past could also be complex, often after the loss of a parent, and especially after the upheaval of war.

It is very sad that at some point before 1939, Hannah’s husband Jesse was committed to Hull City Mental Hospital, where he remained until his death in 1967. I’ve wondered if his wartime experiences were the cause of his problems, and I hope one day to examine his records. So, Hannah spent another war living apart from her husband. However, in 1939 she was living in Filey; if she stayed there throughout the war, she at least wouldn’t have been subjected to the intense air raids that bombarded Hull yet again, from 1940-45 (with far more casualties and damage than in WW1). Despite all of the hardships that Hannah endured, she lived until 1974, the year before my husband, her great grandson, was born.

We should never forget the millions of young men who lost their lives in the First World War — they experienced hell on earth and were denied the chance to grow old. The fact that Percy died on his 30th birthday has always been particularly poignant to me. But there is an idea that the families back home were getting along with their daily lives as normal, while servicemen suffered overseas. In many parts of the UK, this was simply not true. It is also important to acknowledge the strength and endurance of the families that had to carry on after the war without their loved one, and more practically, without their breadwinner. This included upwards of 200,000 women in Britain who became war widows6 and 350,000 children who lost their father7. Unfortunately I know much less about Hannah’s long life than I do about Percy’s tragically short one, but I have found it meaningful to contemplate the devastating impact that war had on this young family.

- ‘Why JRR Tolkien’s time in East Yorkshire was no picnic – amid airship and submarine attacks‘, 26 Sep 2021, Hull Daily Mail (online)

- ‘Air Raids on Hull‘, 21 Nov 2013, Kingston Upon Hull War Memorial 1914-1918 (ww1hull.com)

- Same as 2.

- ‘Pals, street shrines and Zeppelin raids: Hull in the First World War‘, 3 Sep 2024, thehullstory.com; and ‘Hull’s WW1 Memorials‘ (ww1hull.com)

- ‘The devastating impact of Spanish Flu in Hull as epidemic killed hundreds‘, 20 Mar 2020, Hull Daily Mail

- https://www.westernfrontassociation.com/world-war-i-book-reviews/british-widows-of-the-first-world-war-the-forgotten-legion/

- ‘Children’s Lives in the Great War‘, Voices of War and Peace

Also suggested reading: ‘It’ll all be over by Christmas — Hull in the First World War‘, Paul Gibson’s Hull and East Yorkshire History

This is a wonderful piece of research Clare! I found it incredibly moving to read about Percy’s death and the notices placed in the newspaper every year by his widow on the anniversary of his death (and birth). The account of the battle at Oppy Wood that your found in the battalion diaries was chilling to read. It was a good reminder too to see if there are any resources on specific battalions.

I suspect that Percy’s body was indeed identified and buried at the time. However, the location of many graves were lost with changing battle lines. I have also heard that wooden crosses were sometimes used as firewood by desperate men.

LikeLike

Thank you very much, Jude. That is very interesting about his burial (and extremely sad). Is there a resource on this that you would recommend? I have also wondered what the rites were when there were large numbers of burials.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I would try The Great War Forum: https://www.greatwarforum.org

The guys on there are so knowledgeable and have the answers to these sort of questions. I would be interested to know as well.

LikeLike