Today marks the end of UK Disability History Month (UKDHM). The theme for 2023 has been ‘Disability, Children and Youth’.

In honour of this event I would like to share what little I know of my husband’s second great grandaunt Eliza Saword. Eliza only lived a short life, and appears in very few records, but she has made a lasting impression on me. The 1871 census revealed that Eliza, aged 13, was ‘paralysed’. Ever since seeing that note for the first time, I have wondered what caused her disability, and how it affected her life.

Eliza Saword was born in June 1857 at 1 Fortess Terrace, Kentish Town. (I’ve not been able to obtain a birth certificate with the exact date because the digital download was misaligned). She was the daughter of my husband’s 3x great grandfather, Edward William Turner Saword, an East India Merchant, and his second wife Sarah (née Gibson). Edward Saword was a prolific father, having had eight children with his first wife Emma (three surviving infancy) and nine or ten more with his second wife, including one pair of twins (nine surviving infancy). Eliza was the 12th of at least 17 Saword children.

The family did not have deep roots in Kentish Town. Edward came from a respected Greenwich family, and had married his first wife in Cheshire. The family had lived for several years in Liverpool and Birkenhead. After Emma’s death, Edward remarried to Sarah Gibson, who was 20 years younger than him and had recently immigrated from Ireland to Liverpool. In 1851, the newly-weds, with two children from Edward’s first marriage and one new baby, had emigrated from Liverpool to Boston, intending to settle in America. But by 1853 they had returned to England and made their home in London. More children quickly followed.

Fortess Terrace, where Eliza was born, has not survived. However, a decade before her birth, London watercolourist Edward Henry Dixon captured the view of Highgate Church from the fields opposite Fortess Terrace — an idyllic scene, with people walking through tall grass sprinkled with wildflowers. It may well have still looked much like this when Eliza was born. However, by the 1860s, this semi-rural area was criss-crossed by railway lines.

Published under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) license.

Edward and Sarah baptised their baby daughter Eliza at St John’s, Islington, on 22 August 1858. The long gap of 14 months between her birth and baptism may be significant, although I have not found baptisms of her other siblings in London for comparison. It is likely that Sarah was a Roman Catholic, and I notice that Fortess Terrace was close to a Catholic chapel. Was Eliza’s baptism delayed due to religious preferences, or health problems?

London Metropolitan Archives; London Church of England Parish Registers; Reference Number: P83/Jne/001; via Ancestry.

Between 1860 and 1861, the family had moved again — returning to Cheshire. In the 1861 census they were living at South Seacombe Terrace in Poulton cum Seacombe. Eliza was three years old. The family, with seven children, was able to afford a servant.

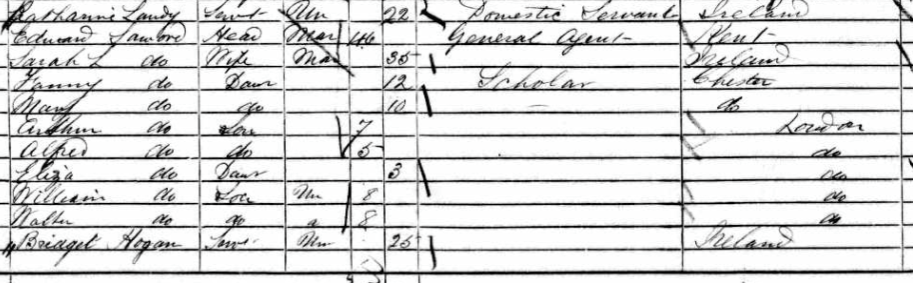

However, within two years they were back in London. And we next find the family in the 1871 census at 25 Union Road, South Hackney, in what appears to be a less comfortable situation than in 1861. Edward was absent, and Sarah was the head of the family, which included five children aged between five and 13; three young adults, two of whom (the men) were working — one as an East India Colonial Broker and one as a West Indian Merchant; and Sarah’s 89-year-old mother in law, also called Sarah. Next door (or opposite) at number 26 was Sarah’s step-son Charles (my husband’s great great grandfather), his wife and six children, and a widowed 59-year-old nurse. That’s 19 people in two houses, and it would have been 20 when Edward was home as well. Union Road still has a row of Victorian houses, each with four stories. These homes would have provided sufficient space for a large family. However, no domestic servants are present in this census.

It’s possible that the family was struggling financially, since Edward was a patient at St Mark’s Hospital, a ‘Hospital for Fistula and other Diseases of the Rectum’. Family letters record that he had travelled to India in 1869 with expectations of making £1000 a year, but he had returned prematurely … with a serious and very unpleasant illness and the stated occupation of just ‘bookkeeper’. Edward’s mother Sarah had been financially independent since becoming a widow 56 years earlier, but perhaps, having reached the age of almost 90, her funds had run out.

But let’s return to Eliza, who was 13 years old in 1871, the age my son is now. Eliza’s younger siblings were scholars (school children), but the education act of the previous year had only made it compulsory to attend school until 12 (and the application of that law was patchy). So, she wasn’t attending school, but she had no occupation either. The only detail giving any insight into her life at that time is found in the furthest right-hand column of the census. This column recorded if someone was ‘Deaf-and-Dumb, Blind, Imbecile or Idiot, or Lunatic’. Although there was no intention to capture physical disabilities, Eliza has a note in her entry: Paralysed.

Looking back at the 1861 census, no entry about her health had been made. However, the equivalent column, then only labelled ‘Whether Blind, or Deaf-and-Dumb’, was even narrower in scope than in 1871, and was not intended to record any other type of information.

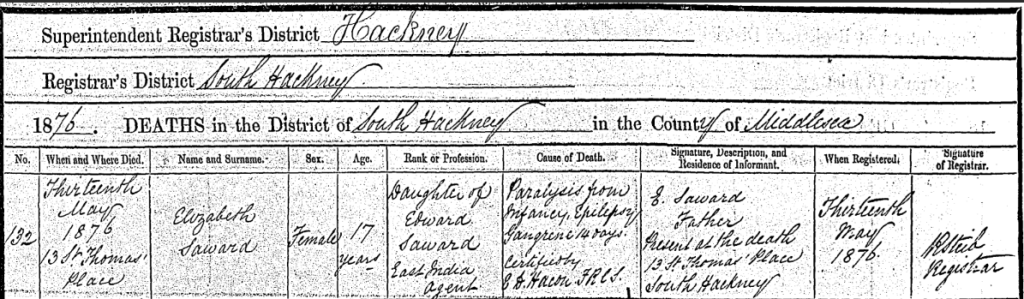

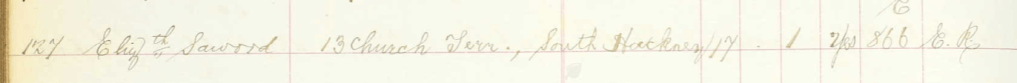

Tragically, the only other document I have for Eliza … five years later … is her death certificate. On 13 May 1876, she died at her home, 13 St Thomas Place, South Hackney (another four-story property). She was 17. Eliza’s cause of death reveals a lifetime of suffering:

Paralysis from Infancy, Epilepsy

Gangrene 14 days

Her painful end was witnessed by her father, who was present at her death. (so, he had presumably recovered from his previous illness, but after Eliza’s death, Edward mysteriously disappears from the records.)

Without any medical records, and lacking medical expertise, it is not possible (or, perhaps, ethical) for me to accurately ‘diagnose’ Eliza. However, by drawing on contemporary sources and modern research into Victorian medicine, I’ve learned about some of the possible causes and treatments of her medical conditions.

The term ‘paralysis’ was used for several conditions and a wide variety of symptoms in the 1800s. You might have come across the term ‘general paralysis’, or ‘general paralysis of the insane’, which was used for people suffering from the final stages of syphilis, who were often inmates in ‘lunatic asylums’. Some types of paralysis had their own names, such as ‘apoplexy’ (after a stroke) and ‘palsy’, which indicated partial paralysis, or uncontrollable shaking. However, most of these conditions developed over time, and primarily affected adults. Some other paralysing conditions could be caused in utero, or during birth, such as Little’s Disease/Cerebral Paralysis (cerebral palsy), which was discovered in 18531. However, according to Eliza’s death certificate she had had paralysis since infancy.

In 1869, Dr Mathias Roth, a Hungarian refugee and osteopathic surgeon, published On Paralysis in Infancy, Childhood and Youth, and on the Prevention and Treatment of Paralytic Deformities. This book can be viewed in its entirety via Archive.org. I don’t know how influential the book was at the time, but it offers one window into medical knowledge, treatment and attitudes towards paralysis in the 1860s-70s (although the descriptions of autopsies, and examinations of living children, make for unpleasant reading).

Dr Roth begins by listing numerous causes of different types of ‘infantile paralysis’, which he had observed tended to affect children between the ages of four months and five years. He states that the majority of cases had occurred after a fever, caused by infections such as diphtheria, typhoid fever, scarlatina (scarlet fever), and measles. Other causes of paralysis included epilepsy, injury, and toxins, especially lead and mercury. Many of these causes hold up to modern science. However, his theories on causes of paralysis in adolescents also blamed masturbation and ‘too frequent abuse of the sexual functions’.

Surprisingly, Dr Roth doesn’t mention polio as a cause. The British doctor Michael Underwood first described this disease in 1789, within A Treatise on the Diseases of Children, noting that the disease ‘usually attacks children previously weakened by fever; rarely those under one year of age, or over four years of age.’ Polio was more formally identified in 1860 by German orthopedic surgeon Jacob Heine, who named it ‘Infantile Spinal Paralysis’.2 The polio virus spreads through the blood stream to the central nervous system, where it attacks nerve cells, leading to paralysis. However, it was widely ignored by medical practitioners in the second half of the 19th century.

It is certainly possible that Eliza had contracted a viral or bacterial infection in her first few years of life, which had left her paralysed. However, Eliza also had epilepsy. Could a seizure have left her permanently disabled?

Two of her half-siblings had died of convulsions as infants many years before her birth (Edward, aged three months in 1839 and Frances Anne aged one month in 1844). And according to University of Chicago Medicine, 30-40% of epilepsy is caused by genetic predisposition.3 However, the term ‘convulsions’ was frequently used in association with newborn deaths, and the majority of these would not have been caused by epilepsy. Convulsions, such as those caused by fever, were symptoms of many of the conditions and illnesses that sadly caused high infant mortality in this period.4

Whether caused by an infection, a seizure, physical trauma, or toxins, infant paralysis could result in local paralysis (eg one limb), or, in more severe cases, leave children unable to walk. It could also affect children’s ability to communicate. The extent and nature of Eliza’s paralysis is unknown, but it was considered serious enough that her family noted it in the census. With a significant physical disability, as well as epilepsy, what would Eliza’s life have been like?

Eliza’s father could afford to receive care in a hospital, but as Eliza wasn’t a breadwinner, I don’t know if she would have received any professional medical care. In 1859, a new hospital opened in Westminster: The National Hospital, Queen Square, for Diseases of the Nervous System including Paralysis and Epilepsy. People who could afford treatment paid seven shillings a week.5 This would have been a significant distance to travel for Eliza, however.

If Eliza did receive any medical care, Dr Roth’s book reveals that this might have included electric treatments and surgeries, or gentler therapies such as warm baths and physical manipulation. Roth advocated for the latter; he saw little evidence that electricity improved patients’ conditions, and believed that ‘many a paralytic or deformed patient can be saved from being victimised by that class of orthopedic or other surgeons, whose panacea is but the screw and the knife’. However, Roth was a homeopathic practitioner at a hospital for the poor (as well as a foreigner) and his views were probably not widely endorsed.

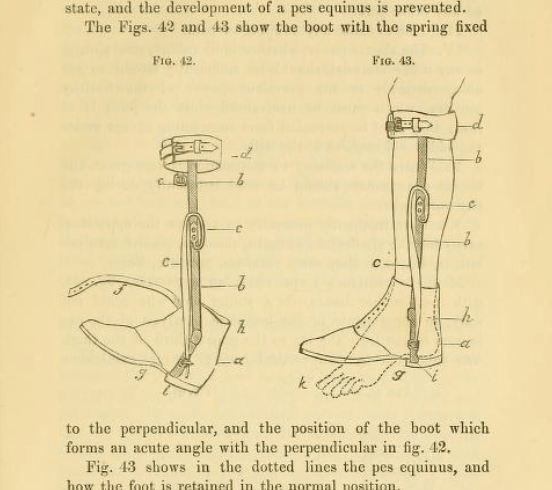

Mechanical supports could also be used to aid movement and walking, such as leg braces and boots. Famously, Dickens’ character Tiny Tim, in A Christmas Carol (1843), suffered from a crippling condition that required him to use a crutch and wear metal braces on his legs. American pediatric pulmonologist Col. Charles Callahan has explored Tiny Tim’s possible diagnoses, including tuberculosis and Potts Disease (tuberculosis of the spine). Edward Saword’s first wife Emma had died of TB, and it’s possible that others in the family were infected.

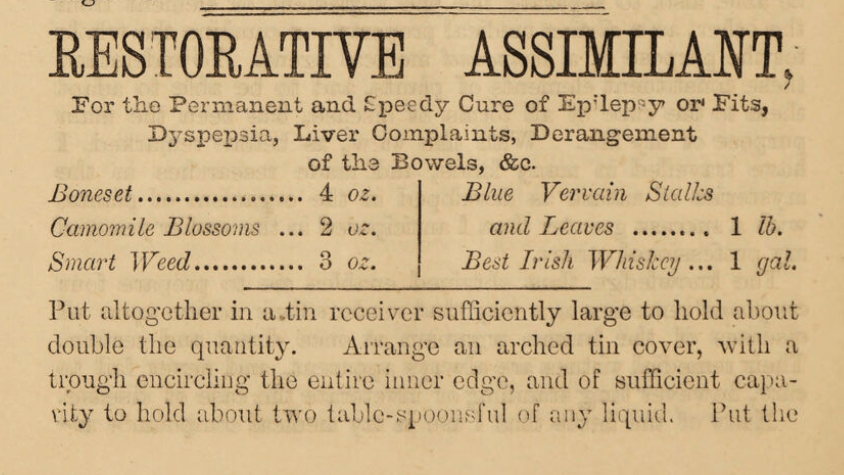

Numerous dubious treatments for epilepsy were on offer in the mid 1800s; many were promoted through newspapers, such as the ‘sure cure’ from Prof. O Phelps Brown of Covent Garden.

Brown, a quack doctor who had made a small fortune in New Jersey, published his Treatise on Epilepsy or Fits in 1869. The entire book, which also includes a treatise on treatment of tuberoculosis, can be viewed online via the Wellcome Collection. After a lengthy introduction about the power of herbal remedies and planetary influences, we see the ingredients for one of his epilepsy remedies …

The first effective anticonvulsive treatment for epilepsy was developed in 1857, using potassium bromide.6 This might have been available to Eliza. However, epilepsy was also very stigmatised. It was hard for people with epilepsy to find jobs, and social pressures to segregate people with epilepsy meant that many ended up in asylums and workhouses.7 In the mid 1800s, epilepsy was the second most common reason for admission to an asylum.8 In the minds of some doctors, the condition was linked to sexual deviancy — a belief that was reinforced by the discovery that potassium bromide also made patients (male and female) impotent.9

Whether or not Eliza benefited (or suffered) from the latest medical developments, she would have needed extra care at home. It’s possible that the nurse who lived in her half-brother’s house next door could have provided care to her as well as to her nieces and nephews, and perhaps also to Eliza’s elderly grandmother. Eliza’s mother Sarah, and perhaps Eliza’s unemployed older sister, Mary, would also probably have been carers to Eliza, among their many other responsibilities. In a crowded house with limited accessibility features (and four floors), and with no public healthcare provision, it must have been a challenge for the whole family.

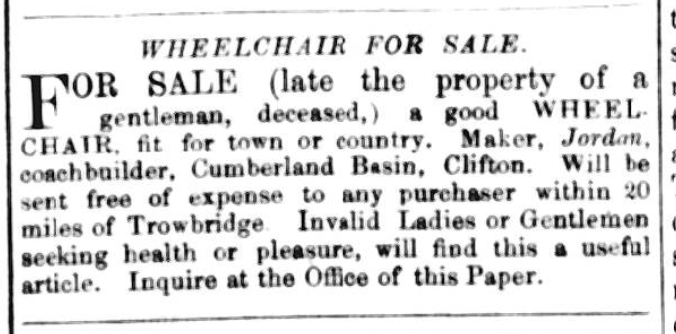

Would Eliza have attended school? By the time school was a legal requirement, she was already older than the minimum leaving age. Her older brothers who worked as clerks must have received an education, but her older sister Mary may not have been so fortunate; unfortunately, none of the Saword children appear in Ancestry’s collection of School Admission and Discharges for schools in London, 1840-1911, sourced from the LMA. In the 1890s, schools sprang up in London for children who were blind, deaf, epileptic or ‘defective’.10 But in the 1860s, Eliza didn’t have those options. If she was unable to walk, she would probably not have been able to travel to school. Early ‘invalid wheelchairs’ did exist in the 1870s, but these were primarily used by the wealthy (see the newspaper advertisement below). There were also makeshift contraptions, so it’s not impossible that Eliza had a means of going to school, church or shops.11 However, the possibility of seizures may have made her completely house-bound.

There is no indication from the census that Eliza had learning disabilities, or any vision impairment, and many members of her family worked in jobs that required literacy, so I think it is plausible that if she could hold a book, she could have learned to read, giving her a pastime. She might have been able to do other seated activities, such as needlework. All of this is conjecture, but helps me paint a fuller picture of what her life might have been like (while also being aware that it might have been much less fulfilling).

Despite Eliza’s disabilities it seems likely that of the three conditions listed under Cause of Death, gangrene is the one that ended her life. And it’s a horrible disease to contemplate: ‘Few medical words strike as much terror in the clinician and the public as gangrene with all its associations of rotting, corruption, and putrefaction.’12 Gangrene could develop at the site of a wound after a surgery or after an injury, if infection set in. However, it can also be a complication of conditions that reduce blood flow, such as diabetes and Raynaud’s Syndrome, and is linked to some viral infections, such as meningitis. Reader rowleyregislosthamlets has pointed out that people who are bed-bound can develop pressure ulcers (bed sores). Even today, these can lead to gangrene13. It is very likely that there were co-morbidities between Eliza’s conditions, and that her immobility caused the gangrene, but it’s also possible that the conditions were unrelated.

Despite advances in treatment during the American Civil War, which greatly improved the survival rate of wounded soldiers who developed gangrene, it continued to have a high mortality rate until antibiotics were developed in the 20th century. If Eliza received any medical treatment for the infection, it would probably have been Bromine, applied topically or injected, which was painful, and could cause other side effects.14 Perhaps the surgeon who certified her death, Dr Hacon of Hackney, had also attended to her over the previous fortnight, or throughout her life. His partner, Dr Toulmin, was Consulting Surgeon to the Infant Orphan Asylum at Wanstead and Surgeon to the Invalid Asylum for Respectable Women in London and Its Vicinity in Stoke Newington, which makes me think that this was a practice that truly cared for women and children.

I find it very sad that I know so little about Eliza’s 17 years of life. And now that I have two healthy teenagers of my own, with their whole lives ahead of them, I find her story even more poignant.

However, whereas some Victorian children with physical and neurological disabilities ended up in asylums, workhouses or on the streets, Eliza was, at least, able to live at home with her family. Her family was far from wealthy, but they had more financial security and and a higher standard of living than many others. Perhaps if Eliza hadn’t developed gangrene, she would have lived many more years, and left more records. Although the majority of this blog post has been about her disabilities and death, I wanted to try to humanise Eliza, because her life was so much more meaningful than the medical problems that dominated official records. I am sure that in her short life she was greatly loved by her family and friends, and experienced joy and laughter. I hope she had a chance to walk, or sit, in tall grass sprinkled with wildflowers.

Eliza Saword was buried on Tuesday 16 May 1876 in the City of London and Tower Hamlets Cemetery. Her death certificate gives her the name ‘Elizabeth’, and the same name is recorded in her burial record. I like to think that rather than this being a mistake, it reflects Eliza’s preference to be called ‘Elizabeth’ as she became a young woman — a small piece of her personality, shining through.

As a final word, I have learned a lot from researching this blog, but it made me realise how little I knew, and how little I still know, about what life was like for disabled people in the past. I was surprised not to find a book on the subject, for example in the popular ‘My Ancestor was a …’ series from the Society of Genealogists. If anyone has any suggestions on resources, I’d be very grateful. Also, do check out the resources on UKDHM.org, which include this fascinating visual history of wheelchairs.

References

- THE HISTORY AND ORIGIN OF CEREBRAL PALSY, yourcpf.org

- History of the eradication of poliomyelitis, Fondation Ipsen

- Causes of Epilepsy, UChicagoMedicine

- Convulsions, University of Leeds Special Collections

- University College London Hospitals: Our History

- Bromide, the first effective antiepileptic agent, J M S Pearce, Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry

- Social Control and the Sane Epileptic, 1850-1950, Susan L Lannon, History of Neurology

- The History of Epilepsy Society

- Epilepsy: a short history, Varsity

- The Daily Life of Disabled People in Victorian England – Community, School and Charity, Historic England

- History of the Wheelchair, Science Museum and Wheelchairs Through Time, UKDHM

- Gangrene, Christopher Lawrence, The Lancet, VOLUME 366, ISSUE 9498, P1689

- Pressure ulcers, NHS Inform

- In a world with no antibiotics, how did doctors treat infections?, Varsity

Most interesting, poor child. Another possible thought on the gangrene is that she was probably bed bound and may have developed pressure sores which are a potential life-threatening problem with immobile people, even today. Today, there are special mattresses and better treatments but there may not have been the awareness then of how to prevent such sores on heels, buttocks, etc.

LikeLike

That’s a really good point, and something I had thought about, but I wasn’t sure if pressure ulcers could lead to gangrene. I’ve checked, and they can indeed. How sad. I will add something to my blog about this. Thank you.

LikeLike