I grew up hearing a romantic story about a mysterious figure in my family history — “Aunt Becky”. Becky was the second wife of my great great grandfather Alfred TALMER, and she was said to be a gypsy — as she lived in a traditional Romani caravan. I recently set out to try to find out whether she really was of gypsy heritage, and what her life had been like before marrying Alfred. My research led me to discover some highly dubious birth registrations, and fascinating links between a London workhouse and a rural village in Buckinghamshire.

Family lore: Aunt Becky

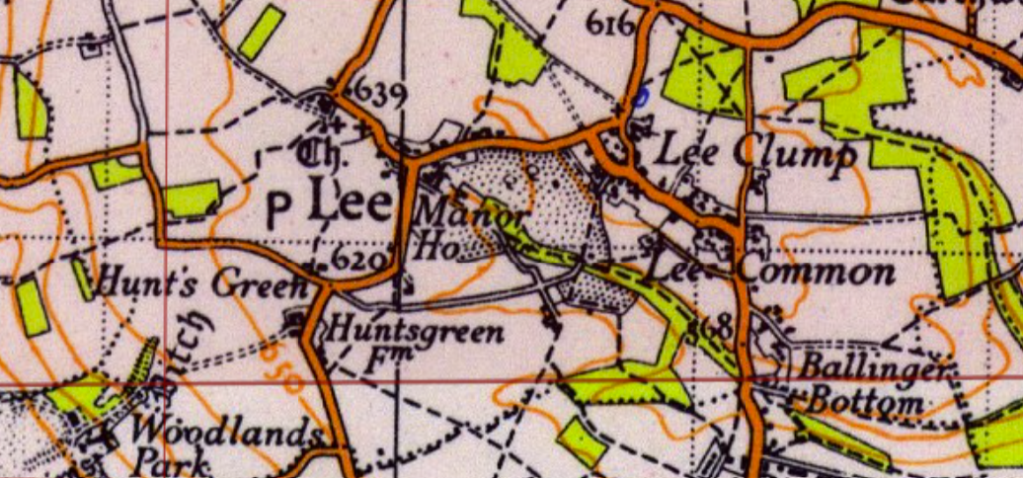

Growing up, my maternal grandmother, Joan Talmer, knew the woman she called Aunt Becky, who lived with Joan’s widowed grandfather Alfred Talmer in the same small village — The Lee, high in the Chiltern hills in Buckinghamshire. Alfred’s wife Emma had died of uterine cancer in 1928, the year before Joan was born. Alfred and Emma had been married for 45 years and had twelve children, two of whom died in childhood and two more while serving in the First World War. Alfred, a farm labourer, was 65 years old when Emma died, and their surviving children were by then all adults. In this new phase of his life he soon found comfort in the arms of the enigmatic Becky.

Fragments of their story were passed down from my grandmother, to my mum, and to me: Becky had a traditional painted gypsy caravan, which stayed in the back garden of their home, Cherry Tree Cottage. She ‘kept house’ for Alfred, and their home was always pristine. The exact nature of their relationship was unclear, but she was known to have been his romantic partner. It was also unclear as to when she moved out of the caravan and into the house. I have never seen the caravan myself, and sadly have no photographs of Alfred or Becky. However, on a family history visit my mum made to The Lee 20 years ago, a dilapidated gypsy caravan could still be seen over the fence of Cherry Tree Cottage. I plan to go back to have a look for it myself, though it does not appear in recent estate agent photographs.

Joan always believed that Becky was a gypsy, but some years ago, my mum spoke to Joan’s youngest sister Margaret about this claim, and Margaret laughed, “noooo, she wasn’t!” In recent years, Margaret’s memories became more muddled, and she died just a few weeks ago — the last of her generation.

Becky wasn’t my ancestor, but I wanted to know more about this intriguing person in my family’s history. Where did she come from? Was she from a community of travelling people, such as Roma gypsies or Irish travellers? And what had brought her to The Lee?

In the late 19th century, these colourful wagons, called vardos, were still a familiar sight in the countryside. Inside, the wagon was often as richly decorated as the exterior, and ingeniously furnished to store everything they needed, as well as being the family’s shelter from the elements.

A legitimate marriage

It’s not uncommon for family historians to discover that a couple with the appearance of being married, were in fact living together without a legal union. But with Becky and Alfred, the opposite was the case — although Becky had appeared to hold the ambiguous positions of housekeeper and romantic companion, and was known to Alfred’s grandchildren as ‘aunt’, I discovered that Becky and Alfred were in fact legally married. Rose Rebecca FLOOD and Alfred Talmer married at Amersham Registry Office on 26 January 1929, a year after his first wife’s death. And it was certainly not a secret ceremony; the marriage was announced in the Buckinghamshire Examiner.

The marriage certificate stated that Becky, a spinster, was the daughter of George Flood, a general labourer (deceased). Witnesses included William Flood, who I thought was perhaps a brother. Interestingly, Becky signed her name, whereas Alfred only made his mark. Bride and groom were both living at Lee Common. Becky was 44 when they married (more than 20 years younger than Alfred) and the couple would have no children of their own. However, the Talmer family was large, and many of Alfred’s children and grandchildren lived nearby.

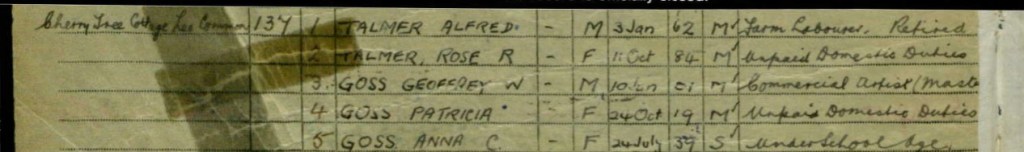

At the outbreak of the Second World War, Rose R Talmer (who I’ll continue to refer to as Becky, unless referring to a specific record), lived with Alfred at Cherry Tree Cottage, Lee Common. Becky gave her birthdate as 11 October 1884. Unfortunately, Alfred didn’t live to see the end of the war; he died in late 1944.

I was able to find a death record for Rose Rebecca Talmer, who died of heart failure on 16 November 1957. Becky was recorded as being 71 years old, which would put her birth in 1885-6. My mum was about six when Becky died, but she doesn’t know if she ever met her, or whether her mum had stayed in contact with her ‘aunt’ after leaving The Lee. My grandparents had no car in the 1950s, and visiting Talmer relations meant a hilly 18-mile round-trip by bicycle from Aylesbury, during limited time off work, so it was a rare occasion.

The search for Becky’s origins begins

Once I knew Becky’s maiden name and had a range of about two years for her birth, I began to look for records of her life before marrying Alfred, starting with a broad search for her in the area of The Lee. In the 1901 census, a 14-year-old girl called Rebecca Flood was boarding in Ballinger, just one mile south of Lee Common, with a poultry breeder called Jane RATCLIFFE. Jane was also hosting another girl, Alice BUTLER, aged 10. The two girls came from Wandsworth Union and their place of birth was unknown. They had no occupation, and neither were they stated to be scholars (school children). The age and proximity to Lee Common suggested that this could be the same Rebecca Flood who married my 2x great grandfather.

However, were there other Rose or Rebecca Floods who might also be candidates? I found that between Q3 1884 and Q4 1886, four Flood girls with names like ‘Rose’ had been born in England (and none in Wales): Rose in Stoke on Trent, Rosanna Rebecca in Wandsworth, Rosina Emily in Shoreditch and Rose Emily in Chelsea. There were no births registered for a Rebecca Flood. The closest match seemed to be Rosanna Rebecca, registered in June quarter, 1885 in Wandsworth — even though the timing didn’t match Becky’s reported birthdate, she had the right middle name to be my Becky and the right birth place to be the girl boarding in Ballinger. I felt I was on the right track, and I was curious to find out what circumstances had brought her from South London to South Buckinghamshire.

Given that two girls had been placed in this rural Bucks village by a London Poor Law Union, I suspected there might be others nearby. I found that the Postmaster and Postmistress of The Lee had three EARMAN brothers boarding with them, aged 8-12 — all ‘boys from the Clapham and Wandsworth Union’. In Great Missenden, next door to The Lee, a woodsman had two boarders, CASTLE brothers aged 13 and 9, born in Wandsworth. The house next door also had two boarders, Albert ROBINSON aged 13 and Arnold TIEMAN?, 7, both born in London. Only the Earman boys were listed as attending school.

Peter Higginbotham’s brilliant website, workhouses.org.uk, on its page about Wandsworth Workhouse, explains that ‘In the 1890s, almost six hundred children in the care of Wandsworth and Clapham Union were at the North Surrey District School at Anerly. Another hundred of the union’s children were boarded out in various parts of the country, 80 were at institutions at Margate, 18 were in a convalescent home, and 100 were at Catholic schools. The union also sent many of its parentless children away to Canada.’ Among these many ‘creative’ ways of outsourcing the care of a huge number of poor children, Becky seems to have been one of those boarded out.

While waiting for an opportunity to investigate the records of Wandsworth Union, I searched for more records of Becky/Rebecca’s life. In the 1911 census there was no sign of her near The Lee, or anywhere else in Bucks. But a Rose Rebecca Flood, 25, was employed as a domestic servant for an Irish family in Worthing, Sussex. She came from Battersea; this tallied with a birth registered in Wandsworth and a child boarded out by Wandsworth Union. In 1921, the same Rose Rebecca Flood was working as a servant for an estate agent and his wife in Hampstead.

Could I find Becky’s family in Battersea before 1901? The index to the birth registration of Rosanna Rebecca Flood in Wandsworth showed that the mother’s maiden name was SPARKS. A search of marriages found only one viable match — between Henry William Flood and Rebecca Sparks in Wandsworth district, 1873. Becky had said her father’s name was George. But I had a hunch that this was the right family, and on delving deeper, I would discover that many of the records of their lives didn’t quite ring true …

London Metropolitan Archives, Reference Number: P85/Tri1/014. via ancestry.co.uk.

The Battersea Floods

The recent availability of instant digital downloads from the General Record Office makes it much more affordable to order birth, marriage and death records — and I was able to download the detailed part of Rosanna Rebecca’s birth certificate for less than the cost of a cappuccino. It gave her birthdate as 17 April 1885 and showed that her parents were, as expected, Henry William and Rebecca.

Next, I looked for the earliest census record I would be able to find for Rosanna Rebecca, in 1891. I found that Rebecca Snr. was a widow in Battersea working as a charwoman. She had three children, and the youngest, ‘Rose’, was four years old. This didn’t quite tally with Rosanna, as she should have been five (about to turn six). However, small variations in age aren’t uncommon in census returns (though it’s more unusual for a child).

Looking back at the 1881 census, I found Rebecca and Henry with four children. Rebecca’s age and the names and ages of the two younger children (Arthur and Ann(ie)) matched the family in 1891, so I was confident these records were for the same family.

It seemed that Henry William had died between the spring of 1886 (nine months before Rose’s birth) and April 1891, when the census was taken. However, the closest matching death record I could find was a Henry Flood who died in Wandsworth, Sep Q, 1883, aged 31. This age corresponded to Henry’s age in the 1881 census, but if this was the same man, it meant he couldn’t be Rosanna’s father. My interest piqued, I downloaded Henry’s death certificate. The address, occupation and wife’s name showed it was the right Henry, and that he had died from phthisis (TB) on 24 September 1883. It meant that Mrs Rebecca Flood had claimed her late husband was her new daughter’s father, one year and seven months after his death! She had also omitted to note in the registration that Henry was ‘deceased’.

But wait, there’s more …

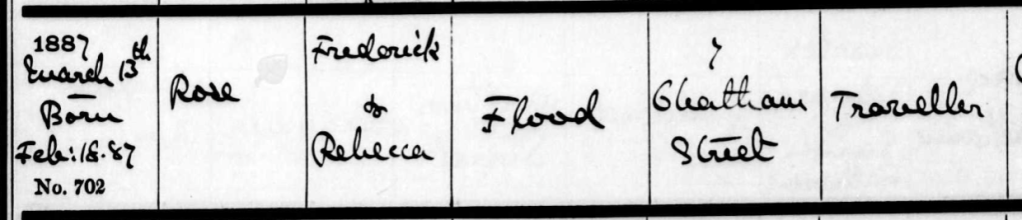

Another online search for information on Rosanna produced a baptism record for Rose Flood at All Saints’, Battersea in 1887. But this Rose was born on 18 Feb 1887. Her parents were Rebecca … and Frederick Flood, who was, very intriguingly, a ‘traveller’. I was able to find this child’s birth in the GRO indexes and her mother’s maiden name was Sparks!

This younger Rose’s birth certificate confirmed that her parents were Fred and Rebecca Flood, and stated that Fred’s occupation was ‘boot repairer’, which was similar to Henry’s occupation of bootmaker/shoemaker. Although it was just possible that there had been two Rebecca Sparks marrying two different Floods, both of whom were bootmakers and had died within a few years of each other, I realised that the age of this Rose fitted perfectly with the Rose who was living with the widowed Rebecca in 1891 (and she was the only Rose Flood living in Battersea that year). But if it was the younger Rose living with her mother in 1891, what had happened to Rosanna Rebecca?

The answer was to be found in the registers of deaths: ‘Rose Hannah Rebecca Flood’ had in fact died at the age of four months. Her mother, when registering the death, stuck to the story that Henry (now admitted to be deceased) was the baby’s father.

I now had a family in Battersea whose surviving daughter, Rose, was born outside of the range for Becky, and who did not have the middle name ‘Rebecca’. The connection was far less robust but by now, I was fully invested! I was intrigued by the falsification of records and the conflicting fathers’ names, and the description of Fred Flood (supposedly Rose’s father) as a ‘traveller’ was tantalising. I knew that Rebecca must have faced financial struggles as a widow with young children, and it seemed plausible that it was this Rose who had been sent by Wandsworth Union to Buckinghamshire. Whether or not this was my ancestor’s family, I wanted to find out more about the girl who had been sent from London to The Lee at the turn of the 20th century.

Wandsworth Union Records

Records of the Wandsworth Union are held at the London Metropolitan Archives (LMA). Workhouse admission and discharge registers there only go back to 1919 but there are many other records. Before visiting, I searched the Poor Law and Board of Guardian Records, 1738-1926 database in Ancestry, which supposedly indexed digitised registers of reports on boarded-out children from 1891-1902 (reference WABG/153/001 and /002) as well as annual creed registers. Creed books had been required for poor law unions since 1868, and captured inmates’ religious affiliations; these registers can be useful alternatives to admission and discharge registers. No records for Floods came up for Wandsworth, but this result was misleading, as I’ll explain shortly …

I had my fingers crossed that Rose/Rebecca Flood would be included in the register of boarded-out children from 1883-1912 (reference WABG/154). The elegant book was neatly divided into sections for towns and villages across the UK where Wandsworth children had been placed. They were not in alphabetical order, but after leafing through villages in Bucks, Beds, Oxon, Suffolk, Surrey, West Sussex and Hants (Aspley Guise, Eversholt, Banbury, Mildenhall, Maulden, Milton Bryan, Penn, Surbiton, Slinfold, Hockliffe & Chalgrove, Nuthurst, and Thornden Hall) … I suddenly came to the section for Little Missenden — a village five miles from The Lee and two miles from Great Missenden. I quickly realised that it wasn’t just a handful of children who had been boarded out there, but dozens! In fact, Little Missenden, with 44 boarders, had one of the largest numbers of children among all of the places; these children had been placed in homes in a number of surrounding villages.

On the first page for Little Missenden (shown above) I spied the entry for Rebecca Flood. It showed that she was an orphan, b. 1886, and had first been boarded out on 24 October 1895, when she was about nine years old. She had been placed with three other families before Jane Ratcliffe (also known as Jane Rackley):

- Mr ? JAMES in Holmer Green (a village in Little Missenden parish) — there were more than 30 James’s there in 1891 (and I’m a James descendant myself); the heads of household were wood-turners and agricultural labourers.

- Jane BURRAGE in Great Missenden town — Jane Burrage/Burridge was a widowed charwoman in 1891, living in a four-room house on the High St with her sister, who was a recipient of parochial relief.1 Perhaps the payment for taking a child in from Wandsworth Union meant that they themselves were no longer dependent on local charity.

- Mr Samuel? PEARCE in Little Missenden village — possibly the agricultural labourer living in a 4-room cottage with five children in the hamlet of Beaumond End in 1891 (but Pearce was a very common name in the area, and features many times in my own tree).

What must it have been like for a little orphaned girl from Battersea to be moved around between four different families in less than seven years? The register describes these families as ‘Foster Parents’. Unfortunately, I have not been able to find out whether the compensation they received would have much exceeded the cost of caring for the children, so it is difficult to know whether money was a motivating factor, or whether there were other influences, such as encouragement from their church. I hope Rebecca was treated with kindness.

In July 1902, Rebecca would have been about 17 years old. The register records that a letter was received about her from Mrs Rackley (Ratcliffe). The details are unclear, but three days later, she left Little Missenden to go into domestic service in Hampstead, and then in December she went to another employer in South Hampstead.

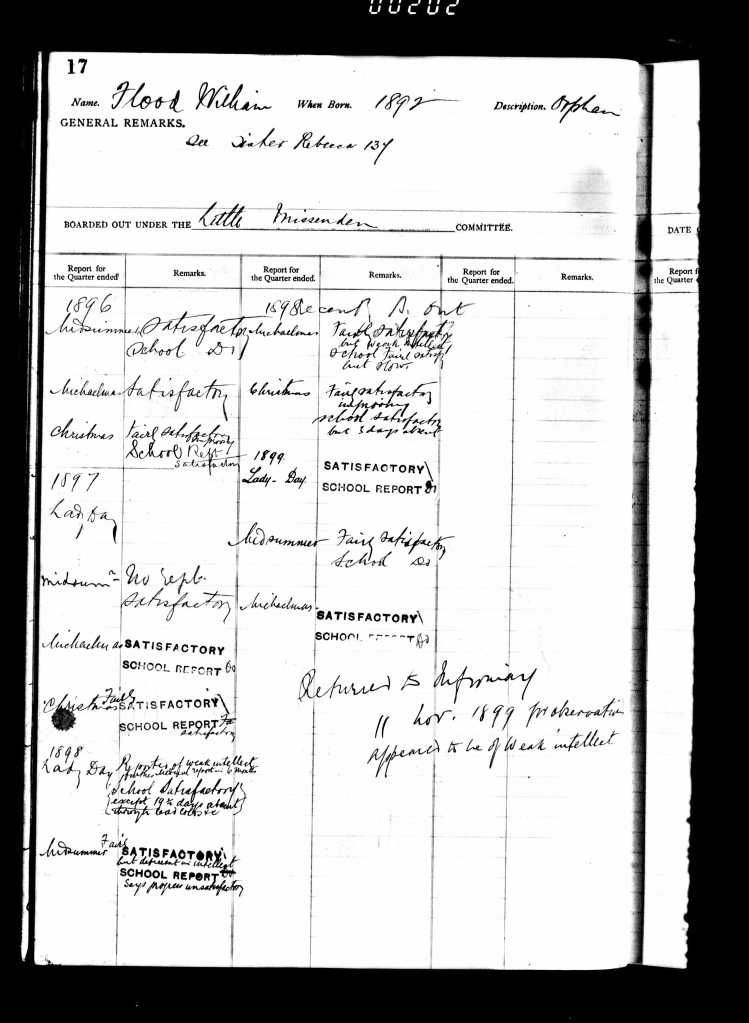

On the final page for Little Missenden, I noticed an entry for William Flood. Most siblings were listed together, and often (though not always) boarded together, but it still seemed likely that William was either a brother or close relation. William had, in fact, had one of the same foster parents as Rebecca — Jane Burrage (his third and final placement). Had they been boarded together for a while? Like Rebecca, William was an orphan. He was born in 1892 (six years after Rebecca) and had been boarded from 1896 (five months later than Rebecca). In 1899 he was discharged to the infirmary, for observation. The notes are hard to read but seem to say he needed ‘bed support’ and that he was ‘said to be fit for imbecile asylum’. Perhaps he was having trouble sleeping, or wetting the bed. William was, after all, just seven years old.

As well as finding Rebecca and a possible sibling in the boarding-out register, I was able to find the other children I had spotted in the 1901 census, including Rebecca’s house-mate Alice Butler, the three Earman (Easeman) brothers, who had two more siblings, and the Castle brothers, whose surname was in fact KOWALSKI.

At the end of the book, after Keswick (showing that children were boarded as far away as the Lake District) and Farnham, was the section for Canada. Hundreds of children were listed there. I found it particularly sad to see that many siblings had been separated and sent to areas hundreds of miles apart. In total, across the UK, 100,000 poor children were sent to Canada, Australia, New Zealand and South Africa, most between 1870 and 1930. Known as the ‘Home Children’, many were used as nothing more than free labour, and suffered abuse and neglect. Despite this, thousands went on to make lives for themselves in their new countries; it’s been estimated that one in ten Canadians today is descended from a ‘Home Child’.

Returning to the Wandsworth Union records, I found it hard to believe that Rebecca and William would not appear in the registers of reports on boarded-out children that were supposed to be in Ancestry. After checking with the helpful experts on the LMA reception desk, they showed me how to browse to that specific record, which is listed under ‘Wandsworth’ and ‘children’. I soon realised that the reports had not been indexed. Furthermore, they had been lumped together with several other records comprising more than 1000 pages in total. (I include this detail as a reminder that Ancestry’s databases are not always as comprehensive as they purport to be!)

Once I had found the right record, the book’s index pointed me to the entries for Rebecca and William. It was well worth the effort — the pages revealed that they had both attended school, and that regular checks had shown them to be satisfactory. I was touched to see that they had been able to receive an education, and that the Wandsworth Union had monitored their progress. However, while Rebecca had continued at school until 17 (four years beyond the minimum leaving age), William had been returned to the infirmary in 1899 (aged seven) and ‘appeared to be of weak intellect’.

As well as the reports on their progress, these records confirmed that Rebecca and William were sister and brother. Rebecca had been boarded following the death of her mother, a widow, in the infirmary on 29 May 1895. At that time William had been in the infirmary as well. The record also shows that Rebecca and William had another brother, Fred, with an address in Battersea.

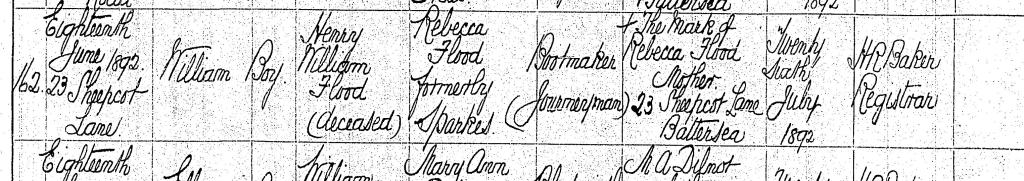

Through a search for death registrations in 1895 I found that Rebecca Flood had died in Wandsworth in June quarter of that year, aged 44. Her name and age confirmed that the girl sent to the Little Missenden area was indeed the daughter of Rebecca, and therefore must have been the girl who was named ‘Rose’ at her birth and baptism. As further corroboration, her older brother Frederick had been living with Henry and Rebecca in 1881.

William was several years younger than Rebecca. So was he another son of the mysterious Fred? His birth certificate reveals that when Rebecca registered his birth she was once again very ‘economical’ with the truth; his father was stated to be ‘Henry William Flood, deceased’. It was quite a stretch to name Henry as the father eight years post mortem! Like Rose (‘Rebecca’), William was baptised at St Stephen’s, Battersea, and his father was named as William Flood, a bootmaker. I am not sure how she was able to have her late husband’s name included in the register; I can only assume that she wasn’t well known to the officiating clergyman.

My final search in the records of the Wandsworth Union were the creed registers, which have also been digitised, but escaped being indexed by Ancestry. These records provided the exact dates of admission into Wandsworth workhouse — Rebecca had been admitted a month before being boarded out — and stated that the children’s religion (creed) was Church of England.

The Wandsworth-Little Missenden Connection

I hoped to learn more about why Little Missenden had been selected as a boarding out location. Minutes of the Union Board revealed that each place had its own boarding out committee, but sadly, no records of the committee have survived. I wondered if the connection between Wandsworth and Little Missenden was Arthur Lasenby Liberty, founder of the famous Liberty’s store on Regent Street. Arthur was born in Chesham, next door to Little Missenden, and his grandparents lived just outside The Lee. In 1898 he purchased the Manor estate of The Lee, becoming Lord of The Manor. He was a major employer in the village, and also a social reformer. His many improvements included new cottages, fresh water pumped from Missenden Valley and a new well. He also improved villagers’ well-being with the provision of a village green, cricket pitch and football ground for their leisure time. Liberty’s Works in London were on the River Wandle (next to what is now called Liberty Avenue). Following the river or road directly north for three miles led straight into the heart of Wandsworth, passing very close to the workhouse. Could Liberty have been involved in persuading villagers in the Little Missenden area to take in poor children from London? Another possible link is James Clark, who was the pastor of the Strict and Particular Baptist chapels at Buckland Common (three miles from the Lee) and Wandsworth. When I next go to the Buckinghamshire Archives I will see what I can find out there.

Was Rose ‘Rebecca’ from Battersea my Becky Flood?

Much as I would like to prove that Rebecca, the girl who had been orphaned in Battersea just after her tenth birthday, was my Becky, there’s evidence that both supports and challenges this theory:

For:

- Becky’s name was ‘Rose Rebecca’ and the girl from Battersea was known as both ‘Rose’ and ‘Rebecca’ (perhaps taking the name Rebecca from her mother and deceased infant older sister).

- William Flood was a witness to Becky’s wedding in 1929, and Rebecca from Battersea had a brother called William, apparently the only sibling who had been boarded out with her (though unfortunately I have found no firm trace of William after he left The Lee as a child in 1899).

- Rebecca from Battersea was trained in domestic service and had years of experience as a servant. From census records I know that her mother was probably also a domestic servant prior to marriage. This background corresponds with Becky’s work as a housekeeper for Alfred, and their immaculate home. (However, domestic service was a very common occupation for women at the turn of the century.)

- I have not come across any other obvious candidate for my Becky Flood.

Against:

- Becky named her father ‘George Flood’ in her marriage record. However, the identity of Rebecca’s father was unclear, and it is likely she was illegitimate. She was also orphaned at a very young age, which could have left her with patchy knowledge of her family. She may have had a close relation called George Flood; there were three George Floods in Battersea at the time of her birth, and a George John Flood was a witness to Henry Flood and Rebecca Sparks’s marriage in 1873.

- In 1939, Becky gave her birth date as 11 October 1884, whereas Rebecca (Rose) from Battersea was born on 18 February 1887. However, Becky’s reported age at death places her birth between 1885-1886. The age at death could be due to error by the person who reported it, but we could also attribute differences in the birthdates to Becky’s lack of self-knowledge due to her circumstances.

Weighing up the evidence, it seems to me very likely that my ‘Aunt Becky’, was indeed Rose ‘Rebecca’ Flood, the orphan from Wandsworth who, having spent much of her childhood at The Lee (and hopefully having experienced some happiness there), wanted to return to the village as an adult.

Gypsy Rose In The Lee?

I started out with the primary question: Was Becky a gypsy? I’ve found nothing concrete to suggest that Alfred’s wife Becky or Rebecca from Battersea were gypsies or travellers. Birth, marriage and death registrations and baptism registers all included typical street addresses.

I have to bear in mind that ‘Gypsies lived in peri-urban encampments or even cheap lodging in cities over winter alongside working-class populations, making and selling goods, moving in regular circuits across the countryside in the spring and summer, picking up seasonal work, hawking and attending fairs.’2 So, a street address isn’t proof of a fixed abode. However, after Rebecca’s father’s death, her oldest brother (Henry William, known as Harry) attended school in Battersea regularly for four years, suggesting the family was settled there throughout that period.

Fred Flood, quite possibly a fake name, was said to be a ‘traveller’. However, that term was also used for commercial travellers, ie merchants or salesmen.

Wandsworth and Battersea were areas with high numbers of Romani gypsies, especially in winter months.3 Looking at the addresses of Rebecca Flood’s family, we do find some alignment with known gypsy encampments in Battersea.

In 1881, the family lived on Culvert Road, which was the long-term site of a gypsy encampment. The Romany & Traveller Family History Society’s website has a page about the Mills family, who lived there in the 1950s. Harry still lived on Culvert Rd in the 1920s. However, the 1881 census for that street includes hundreds of people, and I’ve not seen any entries among them that suggest they were gypsies or travellers.

William Flood was born on Sheepcote Lane in Battersea in 1892. The lane was omitted from Charles Booth’s ‘poverty maps’ from the same period (the road appears but with no colour code). However, a book published in 1951 included a photograph with this description: ‘Down by the railway tracks, hemmed in by streets of little houses, is this caravan encampment. Some of the dwellers in the old vans claim to be of pure Romany stock. Their ancestors came, so they say, year after year in the long ago when all around was Surrey countryside‘. Was the same road also occupied by Romani gypsies six decades earlier?

Below are some excerpts from an essay, ‘Van Dwelling London’, from Living London, published in 1902-3. The full article describes, often through prejudiced eyes, traveller families encamped in Battersea. The photographs are really atmospheric (all three volumes of Living London are available via archive.org).

Brief online searches for Rebecca’s siblings have not yielded any more evidence of a traveller family. What they do reveal are the stark effects of poverty. After Harry left school in Battersea he joined the training ship ‘Exmouth’. When he entered the ship at age 14 he was just 4’7, and when he joined the HMS Impregnable at 16, he was still only five feet tall.

Becky’s caravan

While it’s possible that Becky was from a Roma family, and obtained the caravan from the community in later life, it is also possible that she lived in a caravan in Alfred’s garden simply because it was affordable accommodation. She may even have acquired it from local gypsies; there were certainly gypsies living in the surrounding area; in the 1950s, Roald Dahl bought a cottage at Great Missenden which he named Gipsy House, after some Romani gypsies who lived in nearby woods. He purchased a gypsy caravan in 1960 and it’s still in the garden.

Alternatively, Alfred may have acquired the caravan. Perhaps he offered Becky free board there in exchange for helping him to care for him and his house. The idea that someone who was not of Romani heritage could have acquired a Romani caravan might be surprising. However, by the 1930s, the heyday of these decorative wagons was over.

It’s possible that in the 1930s, Becky and Alfred rented the gypsy caravan out, or lived in it themselves while renting their house. Returning to the 1939 register, we see that they were living with another family at Cherry Tree Cottage: The GOSS family. Geoffrey Goss, aged 38, was a commercial artist, and he and his wife Patricia, who was only 19, had a two-month old daughter, Anna. According to a blog about Geoffrey Walter Goss, which shows samples of his work, he was the grandson of Sir John Goss – composer and organist of St. Paul’s Cathedral. Geoffrey was a successful children’s book illustrator in the UK from 1921 to 1946; his work included several covers for the Tarzan series. During the war the family lived in Harpenden, Herts, and Geoffrey worked at the Vauxhall factory in Luton on designs for the Churchill tanks that were manufactured there. The Goss’s later emigrated to Canada, where both Geoffrey and Patricia had careers as artists; their three children also became artists and musicians.

Although this element of the story might seem like nothing more than an interesting ‘rabbit hole’, the Goss family also provide another clue to Becky’s identity. Geoffrey Goss was born and baptised at Battersea, and in the 1920s he lived in Wandsworth. It seems to me unlikely that this was a coincidence. I have attempted to contact their son, with a hope that he might shed some light on why his parents were living at The Lee, and whether they ever mentioned Becky and her caravan. It’s possible that Geoffrey and Patricia could even have painted a picture of the house, or its owners.

Perhaps one day I will find a photograph or sketch of Becky. Until then, I have used an AI tool to ‘imagine’ her smiling in front of her colourful wagon. After such a difficult start in life, and after spending many years as a servant in someone else’s house, I like to think that in the caravan, and at Cherry Tree Cottage, with my great great grandfather, she finally felt at home.

Update: In July 2025 I was delighted to be contacted by someone whose father was born in The Lee in 1952 and still lives there. He (the father) has always known Cherry Tree Cottage as ‘Becky Talmer’s’! Although he doesn’t remember a caravan in that garden, his great aunt lived in one just around the corner! That would have been in the 1930s-50s. Amazingly, the family still owns the caravan, and have kindly given me permission to share pictures of it below. They hope one day to restore it to its former glory. Is it possible that several caravans were sold to villagers at the same time? Or could this even be Becky’s caravan, that she passed onto a neighbour when she no longer needed it? What’s more, another long-time resident of the village, now in his 80s, has confirmed that the Libertys did indeed have a policy of encouraging local people to take in London orphans. Great stuff!

Romani & Traveller Historical Resources

Romani (Romany) people have been in the UK since the early 16th century, and are thought to have originally come from India.

Who Do You Think You Are has a good guide to gypsy family history. The Romany and Traveller Family History Society has many free records on its website. You can learn about different travelling communities at The Traveller Movement. Some websites about gypsy history in London include the London Gypsies and Travellers History and Heritage Map and ‘Gypsies and Travellers’ on Old Bailey Online.

References

- 1891 England Census; Class: RG12; Piece: 1128; Folio: 20; Page: 10.

- Britain’s Gypsy Travellers: A People on the Outside (History Today)

- https://www.ucl.ac.uk/bartlett/architecture/sites/bartlett/files/50_introduction.pdf

Updated on 18/9/25 to add the information and photos from John Pearce

I loved reading about your research into Becky Flood’s family background. You demonstrated great detective work to piece it all together. I didn’t know much about the poor law unions sending orphans from the cities into the countryside to be boarded out so it was fascinating to see the detailed records that were kept. There must be some parallels between the experiences of the children and those of evacuees, fifty or so years later.

LikeLike

Thanks, Jude. As I was watching ‘DNA Family Secrets’ last week, which included the case of an evacuee, I was thinking the same thing – it was a similar experience but 40 years earlier. I wonder if, as often happened with evacuees, families came to the village hall to choose the children they would take. It is more likely that children from the poor law union came to the village a few at a time, and that the boarding-out committee made arrangements with local families in advance. Of course, unlike most evacuees, these children had no parents or home to return to. I’ve also read this article today – a disturbing story from the 1950s about children taken from their families in Greenland and placed with Danish foster families to make them more Danish. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/magazine-33060450

LikeLike

Bit of a longshot and probably no relation. My most recent blog is about my research on the Berkshire bee van. One of the bee-experts who drove this horse-drawn vehicle was Thomas Flood – he has a collection named after him in the Museum of English Rural Life in Reading, Berks.

Anyway, the wagon was made in Hereford by H. Jones and son who built all sorts of vans including ones for gypsies. The company continued into the 20th century albeit in their apprentice’s name; Cox.

Do you know what type of gypsy van Becky lived?

LikeLike

Thanks so much for getting in touch. I’m afraid I don’t know anything else about her caravan. But that’s very interesting – I’ll have to look into the Thomas Flood collection.

By the way, I have eaten your honey! I worked at the Vale and Downland Museum for a while. I am local to you. I don’t suppose you know my beekeeper-author neighbour Andrew Bax?

LikeLike

Are you sure you’ve eaten my honey? I don’t sell at the museum (yet) :).

I don’t know Andrew but Drayton is not too far from where I live.

If you live in the Wantage area, I would be happy to meet up for a chat – if you think that would be useful (not a problem if you don’t). You can reach me via my contacts page at my website: https://www.beehiveyourself.co.uk/contact/

Kind regards

Steven

LikeLiked by 1 person

Could you point me to the Thomas Flood collection? I’ve not found it in the MERL’s collections database. Many thanks!

LikeLike

This link should take you to the Flood Collection: https://rdg.ent.sirsidynix.net.uk/client/en_GB/merl/search/detailnonmodal/ent:$002f$002fUOR_ADLIB_ARC$002f0$002fUOR_ADLIB_ARC:110013212/ada?qu=Flood+Collection&d=ent%3A%2F%2FUOR_ADLIB_ARC%2F0%2FUOR_ADLIB_ARC%3A110013212%7EADLIB_ARC%7E0&lm=MERL2

LikeLiked by 1 person