Part 2: Lucy & Charlotte Bridgman, Eliza Maultby

In Part 1 I shared the tragic story of Anne Benwell, whose dress caught fire in 1819, causing fatal injuries. In Part 2, we move from the Regency to the Victorian era, looking at three more accidents in which dresses caught fire.

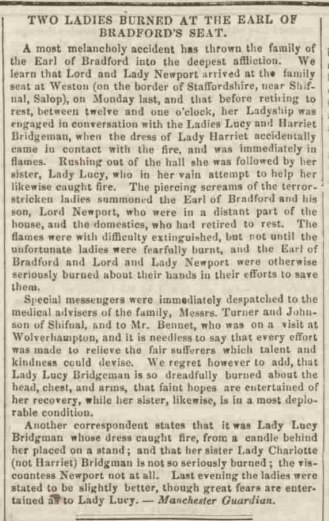

On 15 November 1858, two daughters of the Earl of Bradford, Lucy (b. 1826) and Charlotte (b. 1827), pioneers in photography, were involved in a ‘CALAMITOUS ACCIDENT BY BURNING’ in their home, Weston Park, Staffordshire. The two ladies were talking with their mother and sister in the drawing room, when one of their dresses ‘came in contact with the fire, and was immediately in flames.’ (another account states that a candle, not a fireplace, was responsible). One report states that Charlotte caught fire first and rushed into the hall, followed by Lady Lucy, ‘who, in her vain attempt to help her, likewise caught fire.’ Another version claimed that Lucy’s dress had been set alight first. Whichever was accurate, the ‘terror-stricken ladies’ were ‘fearfully burned’ and tragically did not survive the ordeal; Charlotte died on 26 November and Lucy on 10 December.

Oxford Chronicle and Reading Gazette,

20 November 1858, via BritishNewspaperArchive.co.uk (Charlotte incorrectly named Harriet)

Westmorland Gazette, 20 November 1858, via BritishNewspaperArchive.co.uk

Ladies Lucy and Charlotte died when crinolines were in vogue (see Part 1). However, the only detail I have seen about their clothing when the accident occurred, is in the Wikipedia entry for the family which states that their dresses were made of cotton. Photographs taken by Lucy, in the collection of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, give us a sense of the clothing worn in the family at that time. Skirts were certainly very full, but there are no huge crinolines to be seen.

Lady Charlotte’s diaries from 1846-1857 are available to peruse online at http://ladycharlottesdiaries.co.uk/. Here I learned that only ten years before Charlotte and Lucy died, their grandmother, Lady Elizabeth Moncreiffe (nee Ramsay), also died due to her clothes catching alight, at the age of 78. Lady Charlotte recorded the event in her diary on 3 June 1848 as follows:

‘When we came home we were much alarmed to hear that Grandmama had set herself on fire & was much burnt. We drove immediately to her lodgings & learnt then the particulars from Lucy & Miss Baker who had gone there immediately on hearing it. She did it about 9 ock. while arranging some flowers in a glass, she set fire to her cap & collar, & the curtains of the room. Her neck & hands are dreadfully burnt & the side of her face. Mr. Scannell (?) had been sent for (Mr. Hunter being out) but knowing nothing of him Papa went to Mr. Greufell’s to ask him if he knew anyting about him. He was spoken highly of, so no one else was sent for tonight.‘

Over the next several days, Charlotte wrote that her grandmama was ‘going on well’, but on 17 June, ‘We were sent for to go to Grandmama who was sinking rapidly. We sent to Louisa Moncreiffe immediately who came directly & Tom followed shortly. Newport also went with us there. She died about 1/2 past 1 having been totally unconscious of anything all the time we were with her & for some hours before.’

In the week following Lucy & Charlotte’s deaths, The Medical Times issued a statement that women’s dresses ought to be made ‘blaze proof’. Other readers wrote to their newspaper with their own advice, like L.J., who advised, ‘SIR – if ladies would always keep the wire fireguard on their fire bars, we should hear no more of burnings to death, arriving from collision of their light dresses with live coals or flame.’

Staffordshire Advertiser, 11 Dec 1858

via BritishNewspaperArchive.co.uk

Belfast Morning News, 14 Dec 1858

via BritishNewspaperArchive.co.uk

The tragic deaths of Ladies Lucy and Charlotte Bridgman and Lady Moncreiffe made national news and inspired efforts and ideas to reduce the risks. However, accidents continued to happen, and papers continued to report them. In 1873, a local Bucks paper reported on an accident that involved my 3x great grandmother, Eliza Maultby.

Eliza Maultby (nee Randall) and Thomas Maultby were married in 1865, and in 1867, after the sad loss of their first child, they moved to Newport Pagnell in Bucks, where Thomas took up the post of Station Master at the new station. By 1873, they had four children aged five and under, the oldest being my great-great grandmother. Thomas soon became manager of the Newport Pagnell Railway Company, and newspaper reports indicate it was a very busy job which also required him to travel. On the evening of 30 September 1873, Thomas was out, perhaps working, leaving Eliza, then 35 years old, at home to care for their children. Eliza had just tucked in her youngest child, Richard, who was almost two. Suddenly, Richard called her attention to a light in the room. In the next few minutes, Eliza’s quick reactions saved her and her children’s lives:

NARROW ESCAPE FROM FIRE

A narrow escape from a serious fire occurred on Tuesday evening last, on the premises of Mr. Thomas Maultby railway manager, who was from home at the time. Shortly after Mrs. Maultby had put her youngest child to bed her attention was called by the child to a light in the room, and on going there she found the window curtains and blind in a blaze. She set to work to arrest the progress of the fire, which she succeeded in doing, but not before her own dress had caught. She however had the presence of mind to wrap herself up tightly, and thus preventing further danger, although her hands were considerably burned. the curtains and blind were completely destroyed, the dressing table was charred, and the carpet scorched. It was very fortunate that the fire was discovered so opportunely, or the consequences would no doubt have been serious, if not disastrous. It is conjectured that it was caused by a spark from the candle used by Mrs. Maultby in putting the child to bed.

Croydon’s Weekly Standard (a Newport Pagnell paper), 4 October 1873

Sadly, I have no photographs of Eliza, and it’s difficult to know what kind of dress a lower middle class woman would have been wearing at home on an autumn evening. The 1870s was a bustle era, but a house dress would surely have been simpler and more practical. I imagine her looking much like Harry French’s 1870 engraving for Hard Times, included at the top of this blog. Perhaps she wore a shawl or short jacket for warmth. To extinguish the flames, she may have wrapped herself in more curtains and drapes, bed linens, or simply folds of her skirt that had not yet caught fire. By keeping her wits about her, and possibly following advice she had one day read in a newspaper, she prevented a tragedy that was far too common. My brave 3x great grandmother may have had burn scars on her hands for the rest of her life, but she went on to live another 44 years, until 1917. Tragically, though, her son Richard was ultimately killed by another type of fire – enemy fire in the First World War.

Blazing crinolines have become the stuff of legend, and even jokes – from Punch in the 1800s, to favourite fodder for online historical entertainment articles. However, throughout the 19th century, women’s clothing, in a variety of styles, and a naturally hazardous environment, put them at risk of fire-related injuries and death. Learning about accidents that befell my own ancestors has helped me understand just how dangerous it could be to simply go about your life in a dress.

Have you come across any stories of women whose clothing caught fire? I’d be very interested to hear about them. As I have no expertise whatsoever in fashion history, I would also love to hear from any fashion historians on how styles and fabric preferences could have contributed to Anne Benwell and Eliza Maultby’s accidents.

Harry French wood engraving 1870, Illustration for Dickens’s Hard Times | Public Domain / Wikimedia Commons

These stories are shocking and make sad reading. With our practical clothing and houses warmed by central heating, the risk of catching fire nowadays is slim but you can see how perilous it must have been for women in particular then. The fire insurance marks that you sometimes still see on buildings today are a reminder of the very real hazards of fire to property too.

LikeLike