In 1928, my granny (my dad’s mother) broke several records at the tender age of 19 months. This is the story of how she came to be on the front pages of several Canadian newspapers, and what happened next.

The story begins with my great grandmother, Annie Margaret Munday. Annie was born in Aylesbury, Bucks, England, in 1895, to Joseph and Louisa Munday. Joseph, a pub landlord, had a huge family – three children by his first wife and fourteen with Louisa, his second wife. Annie was the fourteenth of seventeen children, and eleven of them were living when she was born (ages 1-26). Sadly, when Annie was between 10-12 years old, three of her siblings died, aged 13, 16 and 19. However, even after that, Annie was still one of twelve. It’s not surprising that in 1911, Annie, with two of her younger siblings and a cousin, lived with her grandmother. At 15 years of age, Annie was working as a Daily Servant.

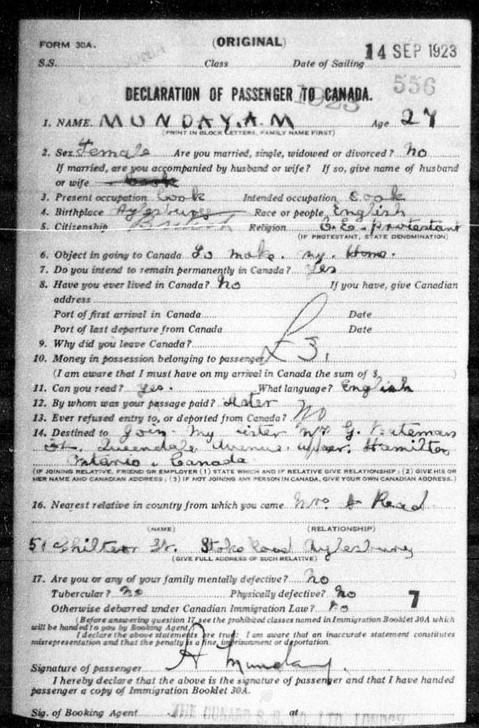

Perhaps it was because the family was so large that some of Annie’s brothers and sisters moved far away from the area in which the Munday family had lived for centuries. Annie’s older brother Alfred went to Edinburgh before WW1, where he became an orchid specialist at the Royal Botanic Gardens. In 1911, her oldest (full) sister Sarah moved with her husband and two young children to Ontario, Canada. Annie’s oldest brother Will and his wife followed them there in 1913. In 1921, both families lived in Hamilton, Ontario. They must have reported back to family in England that life there was treating them well, because on 14 September 1923, Annie set sail for Canada as well. Her passenger declaration (which has just become available to me) shows that she was a cook, aged 27, and that she intended to remain permanently in Canada. Her objective was ‘to make my home’.

Annie’s sister Sarah Bateman had paid for her passage, and Annie intended to join Sarah’s family at their home: 34 Queensdale Avenue, Hamilton.

The next three years of Annie’s life are shrouded from my view. However, during that time, Annie met a man three years younger than her called Walter Emmanuel Raby. And by 1926, at the age of 30, she became became pregnant with his child — my granny.

In 1921, Walter’s parents, Charles and Mary Ann Raby, and six of his siblings, lived just five doors away from the Batemans, at 24 Queensdale. In 1921 Walter was working as a hired man in Mornington, 115 km away, but he must have met Annie on a visit home with his family. Charles’s parents had emigrated from England, and Mary Ann’s from Germany, but they had grown up together in a German household, and one of the very few things that my grandmother ever knew about her father Walter was that he was ‘German’. The large Canadian-German community in Ontario had faced animosity and suspicion during WW1 (the German-founded city of Berlin, halfway between Mornington and Hamilton, had been renamed Kitchener in 1916), and perhaps they were still pariahs. Could this be one reason that rather than marrying Walter, Annie returned to England? Or, did she leave Canada before she knew she was expecting a baby? Either way, Annie arrived back in Aylesbury in time to register the birth of Delia Raby Munday in February 1927.

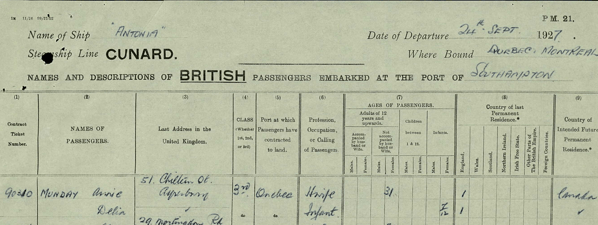

However, in September 1927, Annie headed back to Canada on the Cunard ocean liner RMS Antonia, taking 7-month-old Delia with her!

Did Annie intend to try to get Walter to marry her? It’s pertinent to note that in 1926, the UK enacted a new law, the Legitimacy Act, which gave parents who married after the birth of their child the ability to re-register the child’s birth, making the birth officially legitimate. However, if Annie was on a mission to marry Walter, she must have been unaware that he had in fact got married in November 1926, after he had posted a newspaper ad looking for a wife (!) … and that Walter had also had a baby daughter with his new wife, in May 1927 — only six months after the marriage and just three months after Delia was born! According to family gossip, Walter may not have been the father of this ‘legitimate’ child, since his wife had reputedly answered the newspaper ad out of desperation, finding herself pregnant by her boss! Walter’s actions in marrying a woman, possibly pregnant by another man, rather than Annie, who was carrying his child, are impossible to fathom.

Annie was now a single mother of a baby in a country where she still wasn’t settled, with no possibility of marrying Delia’s father. However, the Mundays in Hamilton weren’t afraid to support an unmarried mother. Annie’s niece, known as Doll, who was only a few years younger than Annie, had had an illegitimate child in 1926, and he seems to have been raised openly within the Munday family.

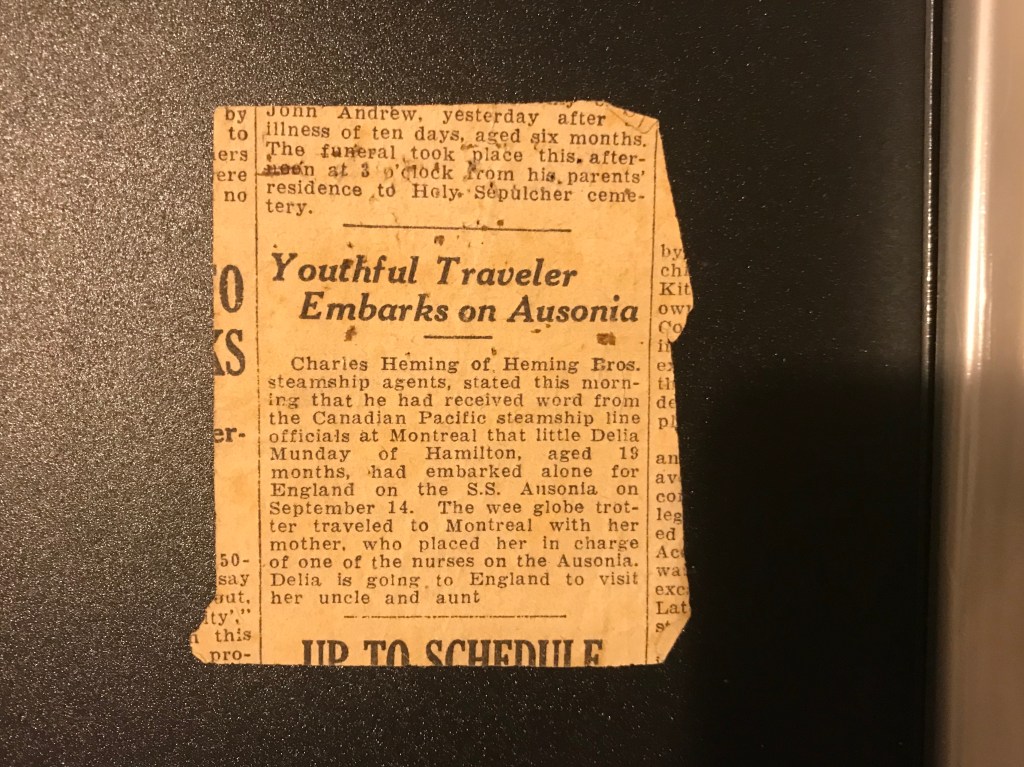

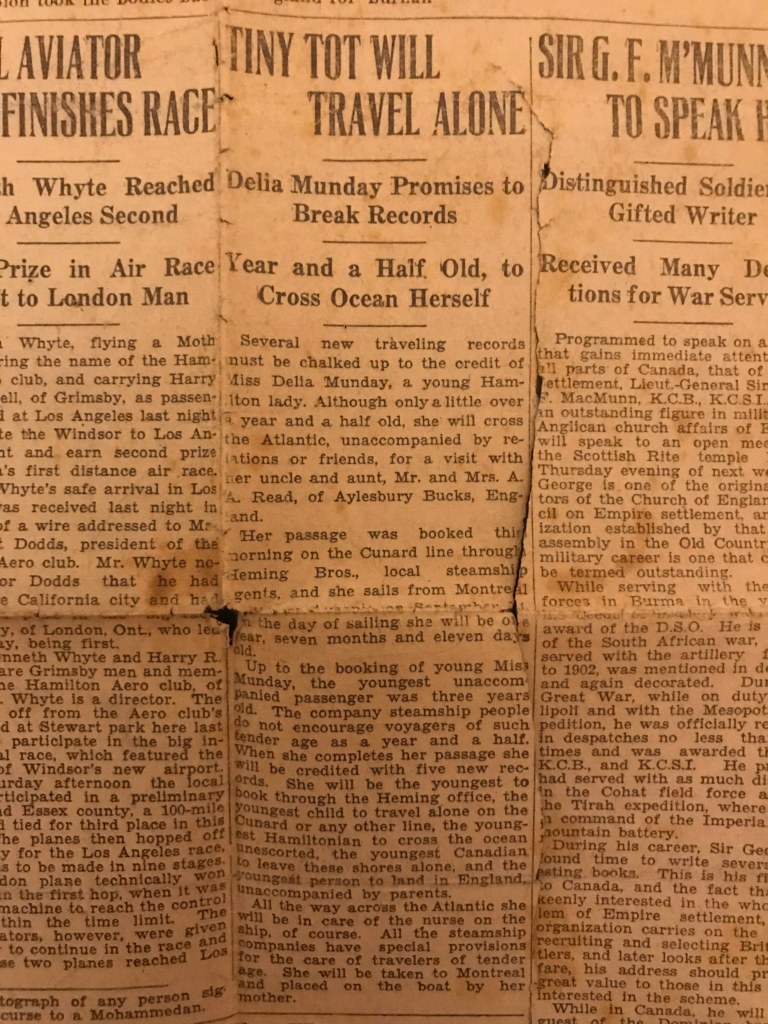

Nevertheless, for reasons unknown, Annie was not able to keep Delia with her. In September 1928, after less than a year in Ontario, Annie obtained a passport for Delia, and on Friday 14 September, when Delia was one year, seven months, 11 days old, she was put on a ship back to England, on her own!

We have several fragile newspaper clippings about this extraordinary event that must have been cut out by Annie. According to the articles, ‘Little Delia Munday’, ‘a young Hamilton lady’, was going to Aylesbury, Bucks, England to visit her aunt and uncle, Mr. & Mrs. A. Read. However, since her parents weren’t mentioned, and it was unprecedented for such a ‘tiny tot [to] travel alone’ to visit relations, I’m sure many people would have read between the lines, and guessed that she was an illegitimate child going to live with family in England. According to the articles in The Hamilton Spectator and Toronto Daily Star, Delia’s trip, ‘unaccompanied by relations or friends’, would break five records, as she would be ‘the youngest to book through the Heming Bros. [local steamship agent] office, the youngest to travel alone on the Cunard or any other line, the youngest Hamiltonian to cross the ocean unescorted, the youngest Canadian to leave these shores alone, and the youngest person to land in England unaccompanied by parents.’ The previous youngest unaccompanied traveller had been three, and the ‘company steamship people do not encourage voyagers of such tender age as a year and a half.’

Delia’s ticket was for the Cunard ocean liner Ausonia (a sister ship to the Antonia). She was to be ‘taken to Montreal and placed on the boat by her mother’ and would cross the Atlantic in the care of the ship’s nurse. As I picture the scene at the port, I wonder what was going through my great grandmother’s mind as she handed her toddler over to the nurse. Did my granny cry? Did Annie know how long it would be before she would see her little daughter again? I wonder who Delia’s nurse chaperone was, and whether she was kind. There were three women passengers on board with the occupation of Nurse, but no clues as to which of them had my granny in her care.

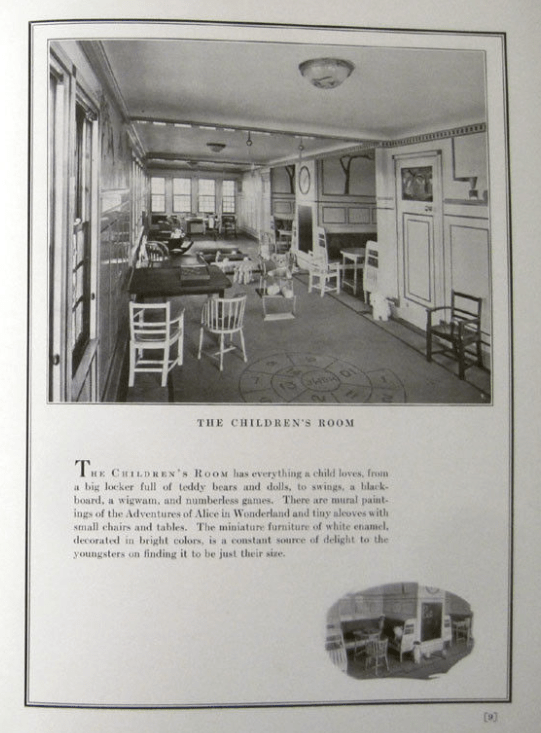

The son of a WW2-era crew member has created a website packed with history and memorabilia about the RMS Ausonia (and her five sister ships). From his website I’ve learned that she was an ‘A Class’ steamship launched in 1921, which accommodated about 1500 cabin class, third class, and tourist class passengers, plus 270 crew. Amenities on board included a children’s nursery, decorated with murals of Alice in Wonderland. The Children’s Room had miniature furniture and was filled with toys, such as teddy bears, dolls, games, swings and a wigwam. If Delia was able to play in those rooms, I hope that they distracted her from her strange surroundings, and her separation from her mother.

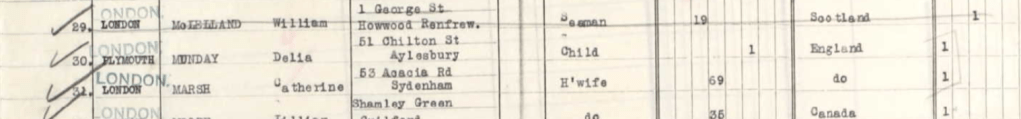

After nine days at sea, Delia arrived at Plymouth on 23 September 1928. Her arrival record shows two number 1s – the first was her age and the second indicated that England was her country of intended future permanent residence. The same record’s ‘Summary of British and Alien Passengers’ shows that she had been one of 20 infants and children (up to 12 years of age) on the journey.

On her arrival in England, Delia was to be met by her aunt and uncle, Charlotte and Arthur Read, who lived at 51, Chiltern Street in Aylesbury. When Delia had first travelled to Canada with her mother as a baby, Annie had given the Reads’ home as her last address, so Delia may well have spent her first few months there. Charlotte Louisa Read née Munday was Annie’s older sister by nine years. She and her husband, Arthur Goodgame Read, had been married since 1909 and apparently weren’t able to have their own children. When Delia joined them in 1928 they were in their early forties. This type of informal ‘open adoption’ between relations was not uncommon. Indeed, Annie’s sister Sarah had emigrated to Canada with her own child (Doll) and an adopted baby — her husband’s cousin, whose mother had died in childbirth. Another possible motivation for Arthur Read to take in his niece was that he had been born out of wedlock himself (though of course it’s possible he didn’t know). In Delia’s case, adoption by her relations allowed a childless couple to raise a child, a single mother to avoid stigma and financial crisis, and an illegitimate child to be raised in a more conventional and financially stable two-parent family.

My granny always called Charlotte and Arthur ‘Auntie’ and ‘Uncle’, but they were like parents to her. However, her mother continued to be closely involved in her life as well. In September 1929, a year after Delia’s arrival in England, Annie arrived in Southampton on the Alaunia. In her passenger record (in TNA series BT26) she was recorded as a ‘Domestic’ who would be staying at Chiltern St, Aylesbury (i.e. with Charlotte, Arthur and Delia). However, her intended country of future permanent residence was still Canada, and less than two months later, another passenger record (in TNA series BT27) shows that she boarded the Ausonia at Southampton, bound for Quebec. I believe that it was during this visit of a few weeks that a charming photograph was taken of Delia standing next to Annie. In my opinion, my granny looks shy and uncertain with her mother — understandable for a child who had not seen her mother for a year. Some lovely studio photographs taken with her aunt and uncle, probably about a year later, show her more at ease.

In June 1931, Annie appeared on the Canada census, as a domestic servant for the family of an English-born salesman in Hamilton, Ontario. She had earned $420 in the past 12 months. Her census entry states that her nationality was ‘Canadian’ (although prior to 1947 residents of Canada were still considered subjects of Great Britain). But Annie’s plans to remain in Canada must have gone awry, or perhaps she simply missed her daughter … because just a few weeks later she was back on the Ausonia bound for England. When Annie disembarked at London on 16 August 1931, she stated her intention to stay in England for good.

In 1939, when the National Register was taken in Britain, Charlotte, Arthur, Annie, and Delia were all living together at Chiltern Street. Annie was working outside of the home in Domestic Duties (probably in a hospital canteen). Their cohabitation surprised my dad, who only knew that his mum had grown up with her auntie and uncle. We have no idea how long this arrangement went on for.

Annie never married, and Delia continued to live with Charlotte and Arthur, who gave her everything they could afford. Arthur was a machine mender’s assistant, and they lived in a tiny terrace house with a scullery and outside toilet, yet Delia had piano lessons, and took a piano exam at the Trinity School of Music in London when she was 11. Delia also did well academically and excelled at sports.

When Delia married in 1947, a photograph of the bride and groom’s parents included her mother (centre) and her aunt and uncle (right).

My dad remembers visiting his nan (Annie), but he saw Charlotte and Arthur, who he also called ‘Auntie’ and ‘Uncle’, far more often. Annie and Arthur passed away when he was a boy, but Charlotte was still alive when I was born, and my dad remained very close to his kind and generous (great) auntie until she passed away in 1981.

My granny never spoke of the mysteries surrounding her childhood. Illegitimacy was hugely stigmatised when she was younger, and it was never discussed. Children did not ask their parents personal questions in those days. When we asked her questions, such as why she was sent back to England, she would simply say “I don’t know.” We have been able to uncover many facts, records, and even photographs of Walter Raby and his ancestors in recent years. However, the truth of what transpired between Annie and Walter was a well guarded secret, never intended to be revealed.

It’s very sad that single mothers found it so hard to keep their children, and I can’t help wondering how my great grandmother felt about giving up her daughter. I also wonder how my granny felt about having been sent away from her mum at such a young age. However, it seems that she had a very happy childhood, and had three parent figures who loved her. In her last years, she wrote, poignantly, that ‘I have enjoyed every moment of my life.’

In Part 1 of this post, I shared the story of Ida Gifford – another ancestor who was also raised by an aunt and uncle while her parents were still alive. Although Ida and Delia’s circumstances were different, I see common threads between their stories. Both had opportunities as children that they might not have had living with their parents, especially as girls. I will never know the motivations or emotions experienced by the people involved, but I believe that in both cases, the parents did what they thought was best for their child.

Postscript, February 2026: I recently inherited a wall clock that belonged to Arthur Read — a retirement award from his employers (Hazell Watson & Viney printers and binders). It means a lot to me to have something that belonged to the kind couple who lovingly raised my grandma.

Updated May 2021.

Updated January 2026 with info about the 1926 legitimacy act, an image of the ship’s children’s room, Delia’s 1928 arrival record and the number of nurses on board, Arthur’s illegitimacy, Annie’s 1929 arrival and departure, the 1931 Canada census, and her arrival in England in 1931.

Incredible story! You can’t imagine a child so young making a Transatlantic trip alone but I’m sure she found some playmates. It sounds as if the arrangements for her care all worked out well in the end.

LikeLike

What a beautiful story and what truly wonderful people Auntie and Uncle were

LikeLike