As the sky outside his bedroom window began to lighten, Dick Mortimer quickly and quietly slid out of his bed. His heart was pounding, but his mind was made up. Dick dressed in a hurry — it was a particularly warm April, and it wouldn’t be cold where he was going. (Would it?) Crouching to the floor, he pulled out a canvas rucksack from under his bed. What to pack? He didn’t dare take his territorial uniform. So, just a few essentials: a change of clothes, a nearly-new can of brill cream, toothbrush … and his filleting knife might come in handy. Dick padded softly downstairs, but he hadn’t been stealthy enough. From his parents’ room his mam called out croakily: “Dick? Are you going out to work?” Dick froze for a moment, and then answered lightly, “Yes, Mam. I’ll see you at tea.” He opened the front door and stepped outside onto Alexandra Terrace. The sun was beginning to rise, and it wasn’t too long until the workday would begin. But the fish would have to cure themselves for a while, because Dick Mortimer was leaving Hull and going where his comrades needed him. He was on his way to Spain.

The summer of 2026 will mark 90 years since the start of the Spanish Civil War. In February 1936, a broad left-wing coalition, the Popular Front, was elected to Spain’s government, but on 17 July, a group of military generals launched an attempted coup. The military rebellion led to a bloody civil war between the right-wing Nationalists (led by General Franco and backed by fascist Germany and Italy) and centre/left-wing Republicans (supported by communist USSR). Although the British government decided not to intervene in the conflict, a few thousand Britons went to Spain voluntarily (and illegally) to support the Republicans. Among them was my husband’s great uncle, Dick Mortimer. When he arrived in Spain in 1937 he was just 18 years old.

Dick was one of ten Hull volunteers (nine men and one woman) who joined the International Brigades, which were organised by The Communist International (Comintern). More than 30,000 men and women joined the brigades from 50+ countries. These volunteers, known in English as ‘brigaders’ or Spanish ‘brigadistas’, arrived in Spain with many different languages and cultures, but united in their determination to defeat fascism and uphold Spain’s democratically-elected government. More broadly, they hoped to hold back the tide of fascism that was sweeping across Europe — British volunteers had also seen this far-right, ultra-nationalist ideology rearing its ugly head in the UK.

The chaotic and brutal war lasted more than three years and resulted in an estimated half a million deaths. The Spanish people — soldiers and civilians alike — suffered an appalling number of fatalities, as well as mass destruction, horrific attrocities and collective trauma. Additionally, about one in five International Brigaders were killed, including more than 500 from Britain and Ireland. However, their service and sacrifice is not very well remembered today.

By telling Dick’s story I hope that I can honour his bravery and integrity. I’ll also share some resources that you could use to research a British International Brigader in your own family tree.

Richard John ‘Dick’ Mortimer was born in Hull on 17 September 1918, just a few weeks before the Armistice. His parents, John (known as ‘Jack’) and Alice, were Londoners (although Jack had Lancashire roots), but by the time of their marriage in 1916, they were based in Hull — where Jack was serving in the Merchant Navy as a steward and cook on board fishing trawlers that had been requisitioned for mine sweeping. After the war, Jack continued to work as a trawler fisherman and cook, and the family became embedded in Hull’s fishing industry. Dick’s younger brother was a trawlerman, and his brother-in-law Harry Kirk (my husband’s grandpa) was a trawlerman. Before and after Dick’s volunteer service in Spain, he worked as a fish curer.

Deep-sea fishing was extremely difficult and dangerous, so trawlermen had copious reasons to be aggrieved with their working conditions. And in the economic ‘great slump’ of the 1930s, which caused high unemployment, workers and out-of-workers in many sectors were drawn to political organisations that championed working-class issues. In Hull, those included local branches of the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB), Socialist Party of Great Britain (SPGB) and the Friends of the Soviet Union, as well as numerous trade unions. Dick’s father was a passionate member of the Communist Party, which as well as focusing on workers’ rights, promoted anti-fascism and anti-colonialism.

The left-wing political movements and trade unions also attracted younger people like Dick through groups such as Hull’s Socialist Youth Club and Young Communist League (YCL). Thanks to two rich online sources of records for British International Brigaders I have insights into Dick’s affiliations. The International Brigade Memorial Trust (IBMT) hosts a free database of biographical profiles for 2400 British and Irish volunteers in the International Brigade. The profiles were created 10-30 years ago and draw on records in the International Brigade Archive (IBA) in the Marx Memorial Library, London and the Russian State Archive of Socio-Political History in Moscow (RGASPI). They also typically include photographs, details from newspapers and information about the later lives of those who survived the war. See Dick’s IBMT profile.

From this excellent resource I know that Dick was a member of the CPGB and the Transport and General Workers’ Union (TGWU), probably because the National Union of British Fishermen had merged with the TGWU in 1922. I also learned that Dick had been a member of the Territorial Army. If he joined the TA prior to volunteering in Spain it cannot have been more than six months earlier, when he’d turned 18, but unlike most Brigaders, he might have at least received some basic military training.

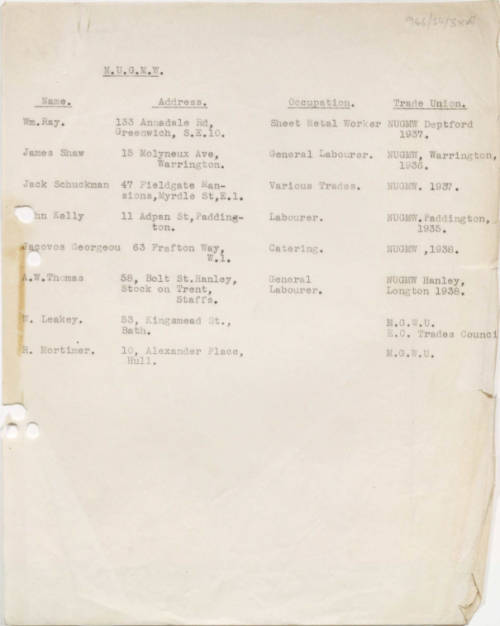

The University of Warwick also holds a large collection of primary sources for the Spanish Civil War, most of it from the archive of the British Trades Union Congress (TUC). Much has been digitised and is available online fo free via Warwick Digital Collections. By searching the collection, I found Richard Mortimer in two lists of IB members who had belonged to a trade union. The first list was sent in November 1938 to the Secretary of the Trades Union Congress by the Secretary of the International Brigade Dependents and Wounded Aid Committee, which had been awarded a TUC grant. The second (below) was produced in 1939. Both lists show that Dick was also a member of the MGWU – the Municipal and General Workers’ Union.

According to Harry Gammon of Hull Socialist Party (writing about Hull’s International Brigaders in 2019), ‘Before they left [for Spain] every one of them was involved in strikes and disputes across the UK and as far away as Australia.’ The experiences of another Hull volunteer, trawlerman Joe Latus, illustrate the types of events that would have shaped Dick’s beliefs and spurred on his activism: In 1934 Joe was fined half a guinea and imprisoned for a week for refusing to fish in severe weather conditions. In July 1936, he was arrested again at ‘The Battle of Corporation Field’ — a violent clash in the centre of Hull between the ‘Blackshirts’ of the British Union of Fascists (BUF), led by Sir Oswald Mosley, and anti-fascist protestors, including Joe.

Like East London’s famous ‘Battle of Cable Street’, which took place three months later, thousands of local anti-fascists showed up at Corporation Field to scupper the BUF’s attempt to hold a paramilitary rally. Among them were trade unionists, dockworkers, railway workers, communists, socialists, Jews (Hull had a large Eastern European Jewish community), and many others. There was violence on both sides — bricks and stones were hurled at the blackshirts, who fought the “reds” off by lashing out with their belts. Far more protestors than fascists were injured, but in the end, the BUF was forced to abandon the rally.

Gammon states that ‘Most of [the Hull International Brigaders] were at Corporation Fields where they fought against and smashed Oswald Mosley’s fascists when they came to our city.’ I think it very likely that Dick and his father Jack were both at Corporation Field that day. However, despite the father and son’s shared politics, Dick kept his decision to volunteer in Spain to himself: whether because his actions were against the law, or simply that he knew that his parents or employer would try to stop him, he left home without telling his parents, and presumably without taking leave from work. At the start of this blog I tried to imagine how Dick felt as he left home at dawn, but that is only speculation. What I do know is that like the vast majority of volunteers, he would have had no combat experience, very little money, and was probably leaving Yorkshire for the first time, and going to a country where he had no local knowledge or language. That was a daunting prospect for a young man who was just 18 years old.

The IBMT database shows the briefest details of Dick’s deployment: He arrived in Spain on 29 April 1937, served with the ’15th Army M.G. [Machine Guns]’. Dick was ‘in hospital sick’ on 7 September 1938, and departed Spain on 7 December 1938.

The XVth International Brigade was made up of volunteers from Britain and Ireland, United States and Canada, the Balkans, France and Belgium, and Cuba. Internal commands and communications were in English. Most British soldiers served in the 16th ‘Saklatvala’ battalion (known as the ‘British battalion’), though a few served alongside North Americans in the 17th ‘Lincoln’ battalion (known as the ‘Lincoln Brigade’). (For those of you researching volunteers from the United States, the Abraham Lincoln Brigade Archives (ALBA) website is an excellent resource and has a database of more than 2800 volunteers from U.S. territories).

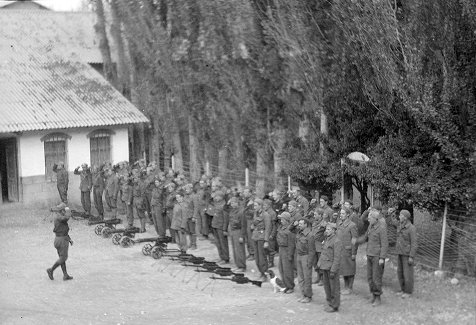

According to the website XV International Brigade in Spain, Dick was in the British battalion. The section about the British battalion features biographies of the brigaders, some of which have details not found in the IBMT database, and is chock-ful of photographs showing groups of volunteers, for example at rest, marching, or standing for inspection.

The Wikipedia page for the British battalion includes a list of notable members; the best-known to me is Laurie Lee, author of a semi-autobiographical trilogy that began with his beloved memoir of childhood in the Cotswolds, Cider with Rosie. The third instalment, A Moment of War, describes his experiences in the International Brigade (it’s on my reading list!)

Dick’s journey to Southern Spain, most likely with at least one other Hull volunteer, probably took him first to London, then Paris, where ComIntern was headquartered. There, he might have been posted to the British battalion, given directions to his base, and given some money and support for the rest of the journey. The final leg was an arduous walk over the Pyrenees. Once in Spain, he was the responsibility of the Spanish Republic, who paid International Brigaders a small daily amount that barely covered expenses. I learned from the superb podcast Journey Through Time, which recently produced a 6-part series on the Spanish Civil War, that despite the brigaders being volunteers, once they had signed up they were effectively trapped in Spain and in military service. There was no defined period of engagement, and leaving the front without permission was viewed as desertion, which was punishable by death. If Dick had a passport, he would have been forced to hand that over on arrival. I think it’s unlikely that Dick traveled with a British passport, but as a Brigader he might have received a special service passport in Paris or Spain.

I am grateful that Dick arrived too late to take part in the devastating Battle of Jarama. However, even if he had left Hull an adventure-seeking and naive idealist, by the time he got to Spain he must have had few doubts that his life was at risk. The volunteers were poorly trained, often unarmed (or armed with old weapons) and were woefully unprepared to face a professional army, with the result that casualties among the brigades at Jarama were shockingly high. During Dick’s service, the British battalion was involved in three key battles, none of which were Republican victories: Brunete (July ’37), Teruel (December ’37 – February ’38), and the Battle of the Ebro (July – November ’38). The Battle of the Ebro was the longest and biggest battle of the war, and was truly harrowing for the combatants. Fighting took place over bare mountains (the Pandols Range) on rocky soil in stifling heat, and the volunteers found themselves without food and water, constantly shot at, and relentlessly bitten by flies. Recollections of the battle on the IBMT website include that of First Aider Alun Menai Williams: ‘It was the worst time in the war. Not for terror, I’d got over that. The agony of the Pandols was that I couldn’t do much for the wounded. Day and night we were being bombarded by aircraft, mortars, shelling and there was no cover. The casualties were horrendous. It was a big, open-air abattoir.’

The International Brigades were withdrawn from action in September and October, and the British battalion left Ebro on 5 October, leaving their Spanish comrades to continue the fight alone. For most volunteers, their time in Spain ended with an emotional farewell parade in Barcelona, at which Republican leaders and supporters thanked them for their service, and thousands of local people showed their appreciation. Finally, British brigaders left Spain en masse on 7 December, travelling to England by train. They were greeted at London’s Victoria Station by Clement Attlee (leader of the Labour Party) and other prominent left-wing and union leaders, as well as thousands of well-wishers, before returning to their home towns and villages across Britain.

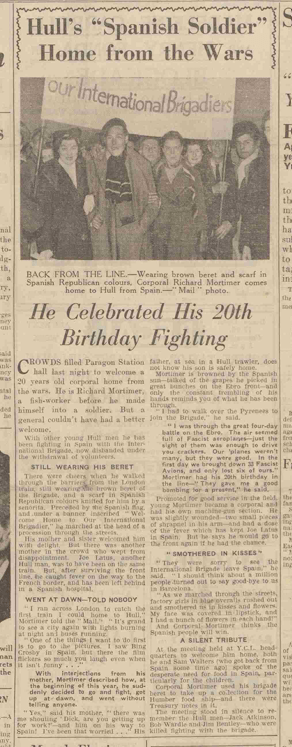

Most of what I know about Dick’s experiences in Spain comes from an ebullient newspaper article published the morning after his joyous return to Hull on 9 December 1938. Beneath the headline about ‘Hull’s “Spanish Soldier”‘ is a photograph of Dick wearing a Basque-style wool beret and a hand-knitted scarf ‘in Republican colours’ (red, yellow and purple) and arm in arm with his proud sisters Lily (my husband’s grandma) and Alice. I love this article so much that I have transcribed it below in full.

(British Newspaper Archive)

Hull’s “Spanish Soldier” Home from the Wars

BACK FROM THE LINE—Wearing brown beret and scarf in Spanish Republican colours, Corporal Richard Mortimer comes home to Hull from Spain.

He Celebrated His 20th Birthday Fighting

CROWDS flled Paragon Station hall last night to welcome a 20 years old corporal home from the wars. He is Richard Mortimer, a fish-worker before he made himself into a soldier. But a general couldn’t have had a better welcome. With other young Hull men he has been fighting in Spain with the International Brigade, now disbanded under the withdrawal of volunteers.

STILL WEARING HIS BERET

There were cheers when he walked through the barriers from the London train, still wearing the brown beret of the Brigade, and a scarf in Spanish Republican colours knitted for him by a senorita. Preceded by the Spanish flag, and under a banner inscribed “Welcome Home to Our International Brigadier,” he marched at the head of aprocession through the streets. His mother and sister welcomed him with delight. But there was another mother in the crowd who wept from disappointment. Joe Latus, another Hull man, was to have been on the same train. But, after surviving the front line, he caught fever on the way to the French border, and has been left behind in a Spanish hospital.

WENT AT DAWN—TOLD NOBODY

“I ran across London to catch the first train I could home to Hull,” Mortimer told the “Mail.” “It’s grand to see a city again with lights burning at night and buses running.

“One of the things I want to do first is to go to the pictures. I saw Bing Crosby in Spain, but there the film flickers so much you laugh even when it isn’t funny …”

With interjections from his mother, Mortimer described how, at the beginning of this year, he suddenly decided to go and fight, got up at dawn, and went without telling anyone.

“Yes,” said his mother, “there was me shouting ‘Dick, are you getting up for work?’—and him on his way to Spain! I’ve been that worried …” His father, at sea in a Hull trawler, does not know his son is safely home.

Mortimer is browned by the Spanish sun—talked of the grapes he picked in great bunches on the Ebro front—and only the constant trembling of his hands reminds you of what he has been through.

“I had to walk over the Pyrenees to join the Brigade,” he said.

“I was through the great four-day battle on the Ebro. The air seemed full of Fascist aeroplanes—just the sight of them was enough to drive you crackers. Our ‘planes weren’t many, but they were good. In the first day we brought down 33 Fascist Avions, and only lost six of ours.” Mortimer had his 20th birthday in the line—”They gave me a good bombing for a present,” he said.

Promoted for good service in the fleld, young Mortimer became a corporal and had his own machine-gun section. He was slightly wounded—two small pleces of shrapnel in his arm—and had a dose of the fever which has kept Joe Latus in Spain. But he says he would go to the front again if he had the chance.

“SMOTHERED IN KISSES”

“They were sorry to see the International Brigade leave Spain.” he said. “I should think about a million people turned out to say good-bye to us in Barcelona.

“As we marched through the streets, factory girls in blue overalls rushed out and smothered us in kisses and flowers. My face was covered in lipstick, and I had a bunch of flowers in each hand!”

And Corporal Mortimer thinks the Spanish people will win.

A SILENT TRIBUTE

At the meeting held at Y.C.L. headquarters to welcome him home, both he and Sam Walters (who got back from Spain some time ago) spoke of the desperate need for food in Spain, particularly for the children.

Corporal Mortimer used his brigade beret to take up a collection for the Humber food ship and there were Treasury notes in it.

The meeting stood in silence to remember the Hull men—Jack Atkinson, Bob Wardle and Jim Bentley—who were killed fighting with the brigade.

Dick was welcomed home to Hull as a hero, and was excited to share tales of his Spanish adventures. Despite the battering that the International Brigade had suffered, he expressed a willingness to return to the front, and a belief that the Republicans would prevail. But the description of his shaking hands — perhaps caused by the shrapnel in his arm or the vibrations of the machine guns — shows the physical and mental toll that combat must have taken on him. So I find it truly moving that within hours of arriving back in Hull, Dick was fund-raising for hungry Spanish children.

Dick’s family must have been incredibly relieved to have him home. Three Hull brigaders were already known to already lost their lives, but by the end of the war, Hull mourned four men:

‘Jack Atkinson died on 21 February 1937 in Jarama. Robert Wardle, aged 28, left his wife and two children to go to Spain and both he and Jim Bentley, 24, died near Calaceite on 31 March 1938 less than a month after they had arrived. Morris Miller, 22, who had written articles for the International Brigade newspaper, was the last of the four to be killed during a battle on Hill 666, near Gandesa in the Ebro offensive of 1938.’1

The IBMT database shows that despite Dick’s promotion and position of responsibility, his service was assessed late in the war as simply ‘Ordinary’. Historian Richard Baxell points out that the assessments were made by political superiors, who were frequently critical or even derogatory — with many volunteers, even those with outstanding military records, unfairly accused of being drunk or disorderly. In that context, ‘ordinary’ seems rather positive! It is clear that the people who had encouraged the volunteers to join the movement did not ultimately show much appreciation for their service and sacrifice.

Furthermore, although returning International Brigaders were not penalised by the British government, some were held under suspicion and might have been subject to continued surveillance. Dick might have been surprised to learn that the MI5 had files on thousands of Britons who fought in the Spanish Civil War, or were supporters of the International Brigades. These files are held at The National Archives in London (series KV 5/112) and were opened to the public in 2010. Each card in the index ‘generally gives name, date / place of birth, address and occupation as well as dates of departure to Spain and return’. In my next visit to TNA I will take a look at the cards for people with surnames beginning with M, to see if Dick Mortimer is among them. Additional MI5 Spanish Civil War records can be found in Series KV 5/113-131.

The Spanish Civil War came to an end on 1 April 1939 with the surrender of the Republican armies. General Franco would rule over Spain for the next 36 years, until his death in 1975. See a simple illustrated timeline of the war.

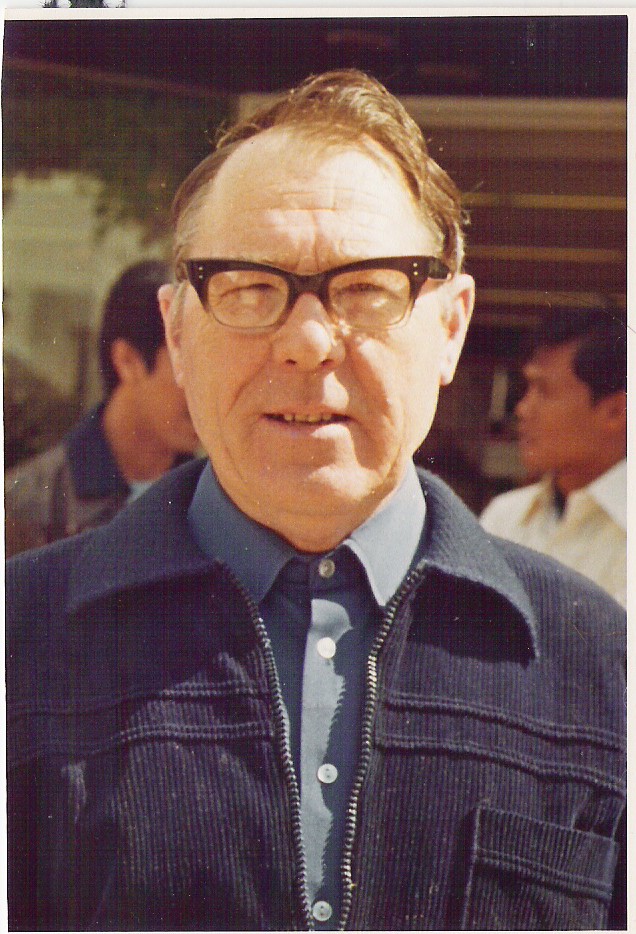

Just nine months after Dick returned home, Britain was facing imminent war with Nazi Germany, and the ‘1939 Register’ was taken to help with wartime planning. Dick was recorded with his family in Hull, once again working as a fish curer. However, his civilian life was shortlived. In WW2, Dick served with the British Army as a Gunner Sergeant —using the skills he had acquired in Spain — and was deployed to Burma. Thankfully, he made it through that horrific campaign as well. I’m hopeful that by 2028 I’ll be able to view his service record at The National Archives (9.3m service records are currently being relocated there from the MOD).

In early 1945 Dick married his sweetheart, Georgina ‘Jean’ Newman. He met Jean in Portsmouth, where she was serving in the ‘Wrens‘ (Women’s Royal Navy Service). Her service in the wrens also earned her the nickname ‘Jenny’. At the end of the war, Dick and Jean settled in Portsmouth, where Dick worked as a Guard for British Rail. The couple had two sons, Richard and Clifford, and several grandchildren.

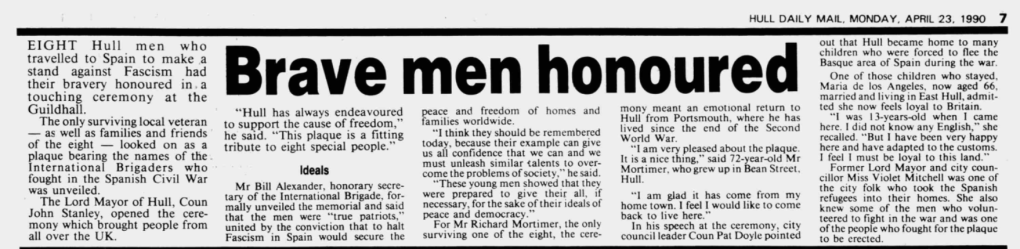

In 1990, Dick attended the unveiling of a plaque in Hull’s City Guildhall to remember eight Hull men who volunteered with the International Brigade (until very recently, only those eight were known to have taken part). At the time of the event, Dick was the last surviving of them. The ceremony was also attended by a woman who had come to Hull as one of 4000 child refugees from the Spanish Civil War, and made it her home.

if necessary, for the sake of their ideals of peace and democracy.”

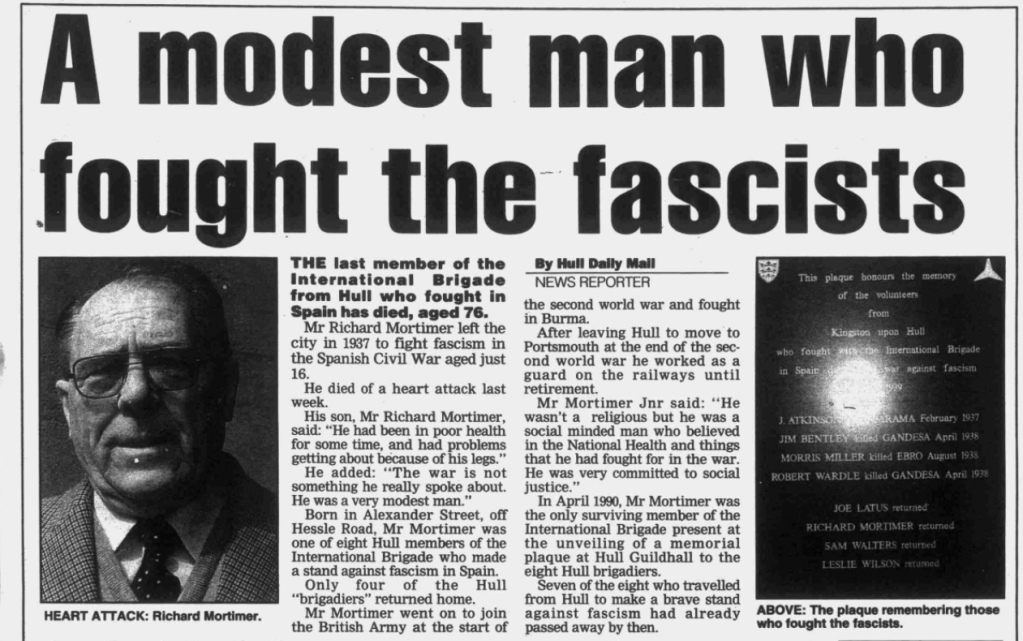

Dick Mortimer died in 1995. In an obituary printed in the Hull Daily Mail, his son, Richard Jr., said that his father was very modest and didn’t speak about the war but that he “believed in the National Health and things that he had fought for in the war. He was very committed to social justice.” Dick’s granddaughter Paula also wrote to me that ‘Grandad was a very proud man and didn’t talk about the war or his part in it.’

In recent years, Dick and his fellow Hull volunteers have been recognised in several creative ways. In 2017, a play, Ocho, by Jane Thornton, told the stories of the eight then-known volunteers from Hull and also the wives they left at home. Featuring songs by Dave Rotheray, lead guitarist for The Beautiful South, it was performed in Yorkshire and Barcelona. Then, in 2019, after three years of fundraising and campaigning by the Hull International Brigade Memorial Group (HIBMG), a memorial sculpture made of Basque marble and Catalonian steel, inscribed with the names of the volunteers, was installed outside the Guildhall. Its unveiling was attended by the brigaders’ families. An exhibition was also held at Hull History Centre, and a documentary produced by Hull College.

George Green was a musician from Stockport and a member of the Communist Party who was killed in action in Spain. Before his death, a letter to his mother reveals the stirring motivation of many British volunteers: “Mother dear, we’re not militarists, nor adventurers nor professional soldiers. But a few days ago on the hills on the other side of the Ebro, I’ve seen a few unemployed lads from the Clyde, and frightened clerks from Willesden stand up (without fortified positions) against an artillery barrage that professional soldiers could not stand up to. And they did it because to hold the line here and now means that we can prevent this battle being fought again on Hampstead Heath or the hills of Derbyshire.”2

I hope that this anniversary year, 2026, the courage and moral convictions of the thousands of young British people who volunteered to join a global fight against fascism in Spain will once again be remembered and celebrated. But this isn’t just history; in the world today, the incendiary political climate of the 1930s feels alarmingly relevant. So, I also hope that the examples of ‘ordinary’ people like Dick Mortimer will inspire us to stand up and speak out against fascism and authoritarianism now, and in the days, months, and years to come.

¡NO PASARAN!

Some key resources for researching British International Brigade volunteers:

- International Brigade Memorial Trust volunteer database

- University of Warwick International Brigade digital collection

- The National Archive MI5 files: lists of persons who fought in Spain 1936-1939

- XV International Brigade: British Battalion

References (all others are embedded as links in the article):

(1) ‘Play remembers eight Hull men who fought in Spanish Civil War‘, BBC News, 24 June 2017 (accessed 15 February 2026).

(2) ‘Remembering the International Brigade’s Fight Against Fascism‘, Challenge Magazine, 20 October 2025 (accessed 15 February 2026).

My thanks to Paula Mortimer, Dick’s granddaughter, for telling me more about her grandfather and sharing the lovely WW2 photograph of Dick and Jean walking arm and arm.