I truly believe that every family history is filled with stories waiting to be discovered. And even the driest of documents can open a door to uncovering those stories. Case in point: I recently researched a name on an old document in my possession, and soon discovered some deaths with unusual circumstances.

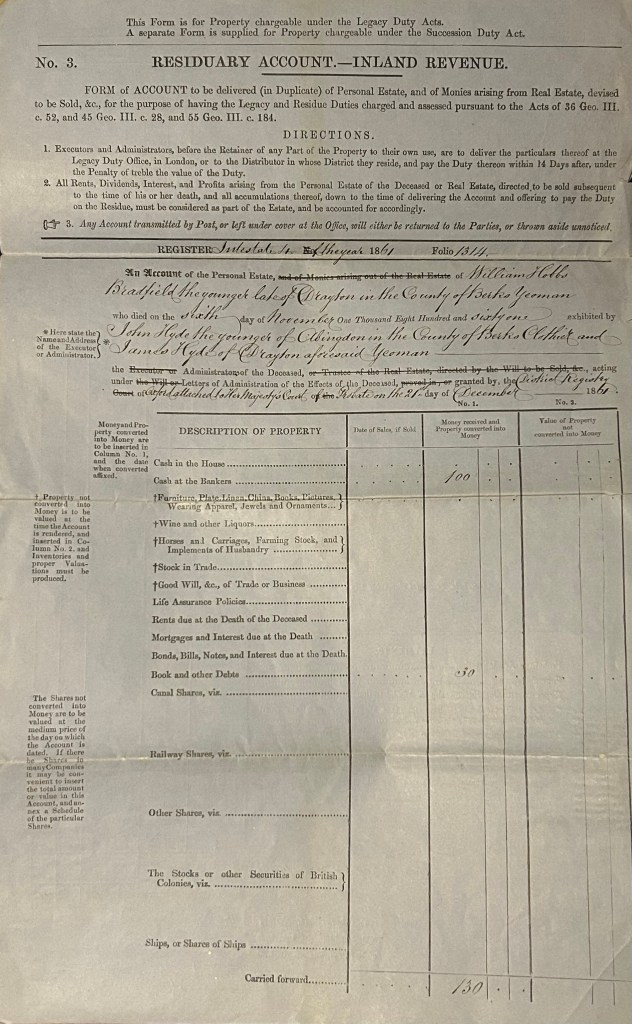

In a collection of old papers from the family who built my house, there’s a large blue document from 1861. It is a residuary account form, which was used to record any property of a deceased person that was chargeable under the Succession Duty Act. At first glance it didn’t look very exciting, and the family I’m researching are only named as executors. But on inspecting the sparse details, my interest was piqued …

The deceased was William Hobbs Bradfield the younger, a yeoman of Drayton, Berkshire, who died intestate on 6 November 1861. From this brief information, I knew that there was also a William Hobbs Bradfield the elder, and that the younger of these namesakes had died first. Were they father and son, and what had happened to the younger man?

Since he had a distinctive name, I did a search of historic newspapers online and quickly found a death notice in the Berkshire Chronicle, 16 November 1861. Despite its typical format, it gave me quite a surprise:

DIED

…

Nov. 6, at Drayton, after a fortnight’s illness, Mr. William Hobbs Bradfield, to the great grief of his friends, aged 24.

Nov. 8, Mr. William Hobbs Bradfield, father of the above, aged 74.

The older William Hobbs Bradfield, who was indeed the father, had died just two days after his son! It must have been a terrible shock for their family. I wondered if they had both died of the same infectious disease, and my curiosity prompted me to download their death certificates.

I learned that the younger William had died of typhoid fever after 14 days with the illness. Typhoid was a scourge in many parts of the world that year. It killed thousands of soldiers in the American Civil War, and just five weeks after William’s death it claimed the life of Queen Victoria’s beloved Prince Albert. Learn about typhoid in the Victorian era from Oxford’s History of Science Museum.

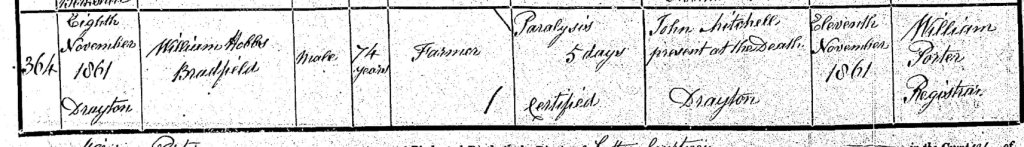

But typhoid was not given as the cause of death of the older William. Rather, he’d been paralysed for five days, and the condition had begun three days before the death of his son. It is difficult to know if the paralysis was caused by typhoid, or perhaps a stroke. In recent years the INTERSTROKE study showed that strong negative emotions (such as being very upset because your son is gravely ill) increase the risk of a stroke.

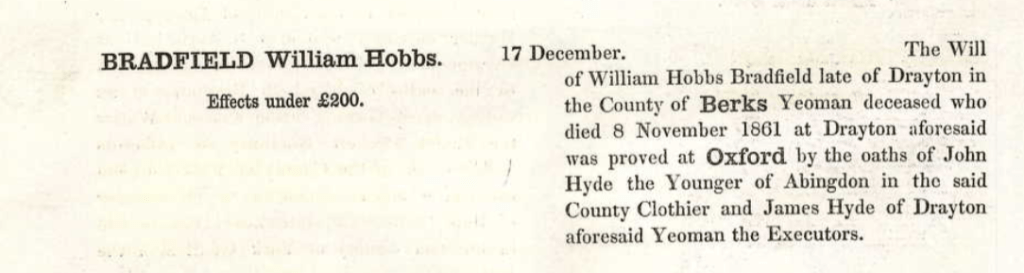

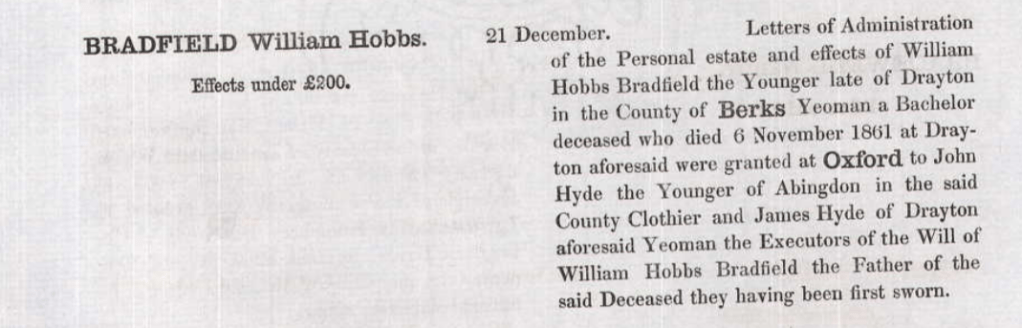

William Hobbs Bradfield Sr. had written a will before his death. I don’t know when he wrote it, or its contents, and as the cost to order a will has recently increased from £1.50 to £16, for now this will have to remain unknown. What I do know is that probate was granted on 17 December to his executors John and James Hyde. And that the same men were granted letters of administration on 21 November for the estate of William Hobbs Bradfield the Younger. Father and son both had effects worth less than £200.

Only eight months before their deaths, the two William Hobbs Bradfields appeared together in the 1861 census.1 William Sr. was a farmer of 15 acres in Drayton, and was a widower. The household also included William Sr.’s 26-year-old unmarried adult daughter, Esther. I later learned she was named after her mother.

After the deaths of both Williams, Esther continued to run the farm herself. In 1871 she farmed 13 acres, living only with her widowed elderly aunt2, and in 1881, she was living with her sister in law, an annuitant, and farming 15 acres3. Then in 1887, at the age of 51, she got married!

Her husband was Robert Langford, a 63-year-old, recently widowed coal merchant from Somerset, who had the main contract to supply coal to the train station at Steventon, immediately south of Drayton. Robert had started life as a labourer but had become a ‘gentleman’ and had built several houses in Steventon village, including Timsbury Villa and an adjacent row of cottages, Timsbury Terrace. Thanks to Steventon History Society I know that Timsbury was the name of the village at the centre of the Somerset coalfield that had made Robert rich.

Tragically, just a few weeks after the wedding, Robert died ‘rather suddenly’ after becoming breathless. An inquest was held on his body in Steventon’s Wesleyan school room, and evidence was heard that he’d had diabetes for many years, and had suffered with a bad cold for 13 weeks. In fact, he had ‘never enjoyed the best of health’. Given Robert’s known medical problems, the coroner ruled it a death by natural causes. ‘His death however was altogether unexpected, and much sympathy is felt for Mrs Langford, who has been forced into widowhood after but a few weeks of married life.’4 I can’t help wondering if anyone harboured suspicions, rather than sympathy.

https://www.steventonhistory.co.uk/people-langfords-webb [accessed 6 December 2025]

After Robert’s death, Esther Langford lived comfortably in Timsbury Villa, ‘on her own means’.5 She died in 1905 aged 70, leaving effects valued at £2647 (£281k today). Her will instructed the sale at auction of several properties, brewery shares and furnishings. However, there were no heirs to her estate, and in 1907, a national newspaper ad sought her Bradfield kin:

NEXT OF KIN

And Others Wanted to their Advantage.

…

Langford, Esther, widow, late of Steventon, Berks, deceased. Heir-at-law wanted.

Bradfield, Thomas, Jonathan, and William Hobbs, all of whom went to America some years ago, or their descendants are believed to be interested in the estate of the said Esther Langford.

(Midland Mail, 23 November 1907)

Thomas and Jonathan were Esther’s uncles. But who was this William Hobbs Bradfield who had emigrated? And did any of Esther’s relations in the United States claim the inheritance?

The wonderful thing about family history is that there is always more to find out!

- 1861 Census of England, The National Archives, RG 9/735, Folio 31, Page 6.

- 1871 Census of England, The National Archives, RG 10/1266, Folio: 32, Page 1.

- 1881 Census of England, The National Archives, RG 11/1286, Folio 30, Page 1.

- Witney Gazette and West Oxfordshire Advertiser, 2 April 1887.

- 1891 Census of England, The National Archives, RG 12/981, Folio 60, Page 5 and the 1901 Census of England, The National Archives, RG 13/1134, Folio 52, Page 18.