The journey of the jolly potters

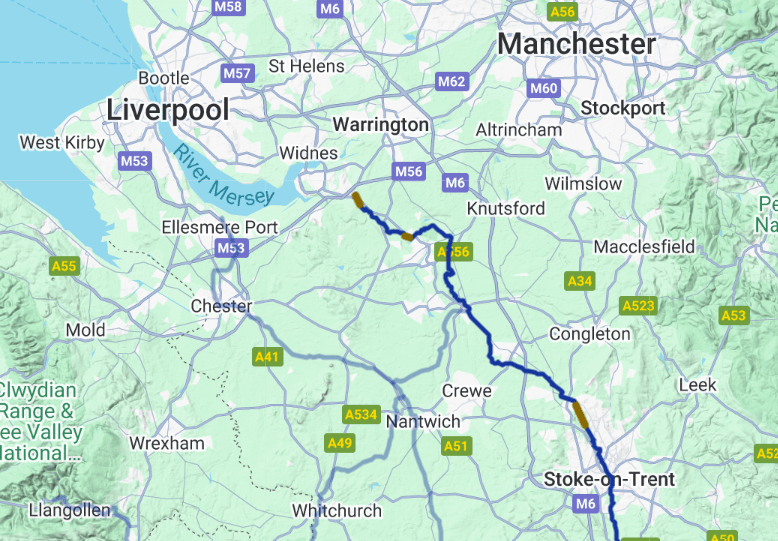

My story begins with a journey from Burslem in Staffordshire to Toxteth in Liverpool in November 1796. A group of 40 to 60 potters and their wives and children left behind the life they knew in Staffordshire and travelled more than 50 miles along the Mersey-Trent Canal to the bustling port town of Liverpool (which was more than 10x the size of Burslem). It was the same route that the goods made at the renowned Staffordshire Potteries took before being exported throughout the world. The waterway, which opened in 1777, had been championed by Josiah Wedgwood and engineered by James Brindley (I learned about Brindley just a few weeks ago, after spotting a memorial fountain to him in a field in his birth parish of Wormhill, Derbyshire).

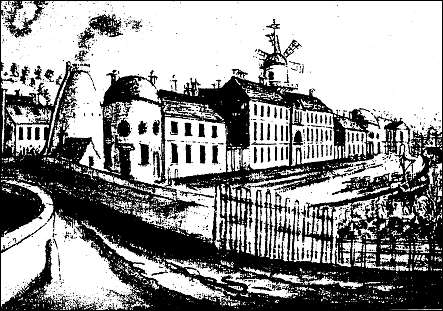

The ease at which pottery wares could be brought from Staffordshire on barges led to such a boom in Liverpool that many Staffordshire potteries had offices and agents at the Liverpool docks. The result was that by the 1790s Liverpool’s own potteries were in ‘severe decline’. But in stepped Samuel Worthington, a savvy businessman who began his career in the silk-weaving trade and then made his fortune in slate mining in North Wales. He saw an opportunity to revitalise Liverpool’s pottery industry by the creation of a pottery factory far bigger than the small potteries currently in operation. Samuel had recruited skilled potters from Staffordshire to get his venture off to a flying start. He also coordinated the materials needed for the pottery from across Britain — including coal from Lancashire, clays from the southwest, colours and moulds from Staffordshire, flint from North Wales and stone from Cornwall. To set his new business apart from the small-scale potteries that were named after their street or owner, he also gave it what we would now recognise as an aspirational brand — inspired by the contemporary passion for Classical antiquity, it would be called Herculaneum.

The journey of Herculaneum’s founding potters was recounted more than 50 years later in charming (and rose-tinted) fashion by the Victorian antiquary Joseph Mayer FSA* in his essay ‘On Liverpool Pottery’. I think it’s really lovely so I’m going to share it in full here:

… the little group of emigrants, who were chiefly from Staffordshire, being ready to start, their employers gave them a dinner at the Legs of Man public house, at Burslem, to which a few of their friends were invited. There they spent the parting night in jollity and mirth; and at a late hour, in conformity with an old Mercian custom, still prevalent in some parts of Staffordshire, the parting cup, was called for, and each pledged the other to a loving remembrance when absent, and a safe journey, with a hearty goodwill.

Next morning, at an early hour, they started on their journey, headed by a band of music and flags bearing appropriate inscriptions, amongst which was one, “Success to the Jolly Potters,” a motto still met with on the signs of the public houses in the Staffordshire pot-districts. When reaching the Grand Trunk canal, which runs near to the town of Burslem, after bidding farewell to all their relatives and friends, they got into the boats prepared for them, and were towed away amid the shouts of hundreds of spectators. Now, however, came the time for thought: they had left their old homes, the hearths of their forefathers, the joys of acquainted neighbours, and were going to a strange place.

Still the hopes of bettering themselves were uppermost in their thoughts, and they arrived at Runcorn in good spirits, having amused themselves in various ways during their canal passage, by singing their peculiar local songs, which, as “craft” songs, perhaps stand unrivalled in any employment; for richness of material, elegance of thought, and expression of passion and sentiment, and it is to be regretted that many of them are daily becoming lost. Amongst other amusements was one that created much merriment — drawing cuts for the houses they were to live in, which had been built for them by their emplovers; and as they had not seen them nor knew anything about them, the only preference to be striven for, was whether it should be No. 1, 2, 3, &c.

At Runcorn they stayed all night, as the weather was bad and the river very rough, after one of those storm-days frequent in the Mersey, when the waters are lashed by the wind into such fury that few boats dare venture out, and many who had never seen salt water before, were afraid to trust themselves upon it in a flat. Next morning, November 11, 1796, the wind had subsided. They embarked on board the flat, and at once, with a fair wind, got into the middle of the Mersey where it becomes more like an inland sea surrounded with lofty mountain ranges. This much surprised the voyagers, alike by its highly picturesque beauty and the vast extent of water. They had a pleasant voyage down the river, and arriving at their destination were met on their landing by a band of music, and marched into the works amidst the cheers of a large crowd of people who had assembled to greet them. Thus commenced the peopling of the little colony called Herculaneum, where, a few years ago, on visiting the old nurse of my father, who had accompanied her son there, I heard the same peculiar dialect of language as is spoken in their mother district, in Staffordshire, which to those not brought up in that locality is nearly unintelligible.

*Joseph Mayer was a Staffordshire man himself, born in Newcastle-under-Lyme in 1803. In his twenties he also made the journey to Liverpool, where he became a goldsmith by trade, and a collector, museum owner, philanthropist and pottery historian for pleasure. In 1857 a photographic portrait of him was the first ever to be ‘made the size of life’. He’ll pop up again a couple more times in this blog …

The Herculaneum Pottery opened on 10 December 1796 at the site of a former copper works on the shore of the Mersey. Worthington was clearly a canny marketeer because the opening was marked by a military band, who paraded from the Works along the docks and streets bearing two colours (flags with pictures), one showing a view of the new ‘manufactory’. The Works launched with about 60 employees. The first production was earthenware, including creamware. According to Mayer, the very first piece made was a blue-printed chamberpot! Another very early piece, now in a private collection in the USA, is a jug of 1796 which features portraits of George Washington along with Chinese-style decoration and a humorous inscription at the centre of the bowl, celebrating ‘A Wonder! An honest Lawyer!!’ As Herculaneum was founded only 20 years after the birth of the United States, exporting patriotic American pieces was good business.

John Edwards of Madeley

One of the most prominent migrant families at the Herculaneum Pottery was the family of John Edwards — my husband’s 4x great grandfather. John was not one of the original ‘little group of emigrants’ but he followed the same path (well, probably a canal) about six years later. Peter Hyland’s informative book, The Herculaneum Pottery: Liverpool’s Forgotten Glory (which draws on an earlier book by Alan Smith), gives some context for the decision of Staffordshire potters like John to migrate to Liverpool and suggests how they would have heard about employment opportunities:

To produce the volume and quality of wares which would make the venture worthwhile, a fairly large and experienced workforce would be needed. There would undoubtedly have been some active or retired pottery workers in Liverpool, but these would not have been numerous and they would not have had the up-to-date knowledge and specialist experience of the potters centred in Staffordshire. Samuel Worthington therefore recruited in Staffordshire, and must have presented an attractive option of working in a new factory on a river-bank amid rolling green fields, and perhaps living in a new cottage. The wages offered must also have been competitive. … For Samuel Worthington to have drawn on Staffordshire sources for his skilled labour force was … not a new idea, though the scale on which he did it was probably unprecedented. The method of recruitment in Staffordshire is not known, and there are no records of advertisements by Worthington in local newspapers. It is likely that an agent was used.

So, it’s likely that John was already a skilled potter before he left Staffordshire, but where did he come from exactly?

John Edwards was baptised in Madeley, Staffordshire on 16 May 1773, the son of a single woman, Sarah Edwards. Sarah had already had another illegitimate child five years earlier. Shortly before John’s birth, Sarah was subjected to a ‘bastardy examination’, where she reported to two Justices of the Peace that the father of her unborn child was Matthew Bedson Junior, a husbandman. Thankfully, Matthew agreed to provide financial support, and a few months after John’s baptism, Sarah and Matthew (then a labourer) were married. Despite being raised by his biological father, John used the name Edwards throughout his life. I don’t know anything concrete about John’s early life but he may have had an elementary education; there was a day school in the Methodist meeting house and a Sunday School at Madeley Wood. Madeley was also being reshaped by the Industrial Revolution. The year that John was born, the first proposal was made to construct an iron bridge which would link Madeley with Brosley and Coalbrookdale. The eponymous Ironbridge was opened in 1780. Despite this boom in local industry, John’s family was not well off; when his grandfather Matthew Bedson Senior died in 1788, he was a pauper.

At the age of about 23, John married Mary Griffith(s) (bp. 1773, Madeley); they tied the knot at St Giles’s, Newcastle-under-Lyme on 23 May 1796. John’s residence at the time was ‘Stoke’ [on Trent]. Less than seven months after John and Mary’s wedding, the first wave of potters embarked on the trip to Herculaneum.

The first record of John’s employment at Herculaneum is in 1807 — by then 150 people worked there and the factory was producing porcelain and bone china. However, he is thought to have come to Liverpool in around 1802, aged about 29. This tallies with the baptisms of his children. There are some possible children baptised to John and Mary in Madeley — Ann in 1796 and Mary in 1799 — but the first child I can attribute to them with confidence is Margaret, baptised in Stoke on Trent in 1798. John, baptised in Stoke in 1799, was also probably their child, but the first son I can be sure of is James Hardy Edwards, baptised in Stoke in 1800. The next known child, Ann, was born in 1802 (place unknown) but wasn’t baptised until 1806, at St Nicholas’s, Liverpool — suggesting a major upheaval for the family between those dates. The baptism register entry for Ann shows that the family of John Edwards, Potter, lived at North Shore. Later baptisms give the family’s residence as Toxteth Park and ‘Pottery’. Since the pottery was in Toxteth Park and on the north shore it’s probable that they lived in pottery housing throughout all of these events. However, Hyland notes a listing in an 1816 directory of Liverpool for a John Edwards, ‘China manufacturer’ with a specific address at 103 Dale Street, though he cannot be sure this is the same man. Dale Street was about 2-3 miles north of the pottery, within the Borough of Liverpool.

A Herculaneum enameller

Although John was recorded generically as a ‘potter’ and possibly ‘china manufacturer’, physical evidence of his work shows that John worked at Herculaneum specifically as an enameller. Enamel could be applied as a single colour over a whole piece or part of a piece, or colours could be combined into highly sophisticated works of decorative art. According to Hyland and Smith, there is only one documented piece that has been attributed to John Edwards; an enamelled porcelain plaque depicting Telemachus and Calypso in the collection of the Museum of Liverpool. John produced the piece in about 1815-20 and it was donated to the museum by Joseph Mayer. I contacted the museum to ask if they would be willing to send me a colour photograph, and when the Curator of Decorative Art responded I got a lovely surprise … They actually have TWO of John’s plaques in the collection: one depicts Telemachus being conducted by Mentor to the Isle of Calypso and its companion piece illustrates Telemachus relating his adventures to Calypso, the Goddess of Silence — both events recounted in Homer’s Odyssey. Hyland calls them ‘the work of a highly schooled artist in the classical tradition.’

©National Museums Liverpool, Walker Art Gallery

Given that John was born into a working-class family I find the quality of his painting quite remarkable. It’s even more impressive when you consider that to make the images, John had to apply powdered glass to the unfired ceramic surface. Only when fired would it melt and transform into a painting that bonded to the ceramic to produce the finished piece.

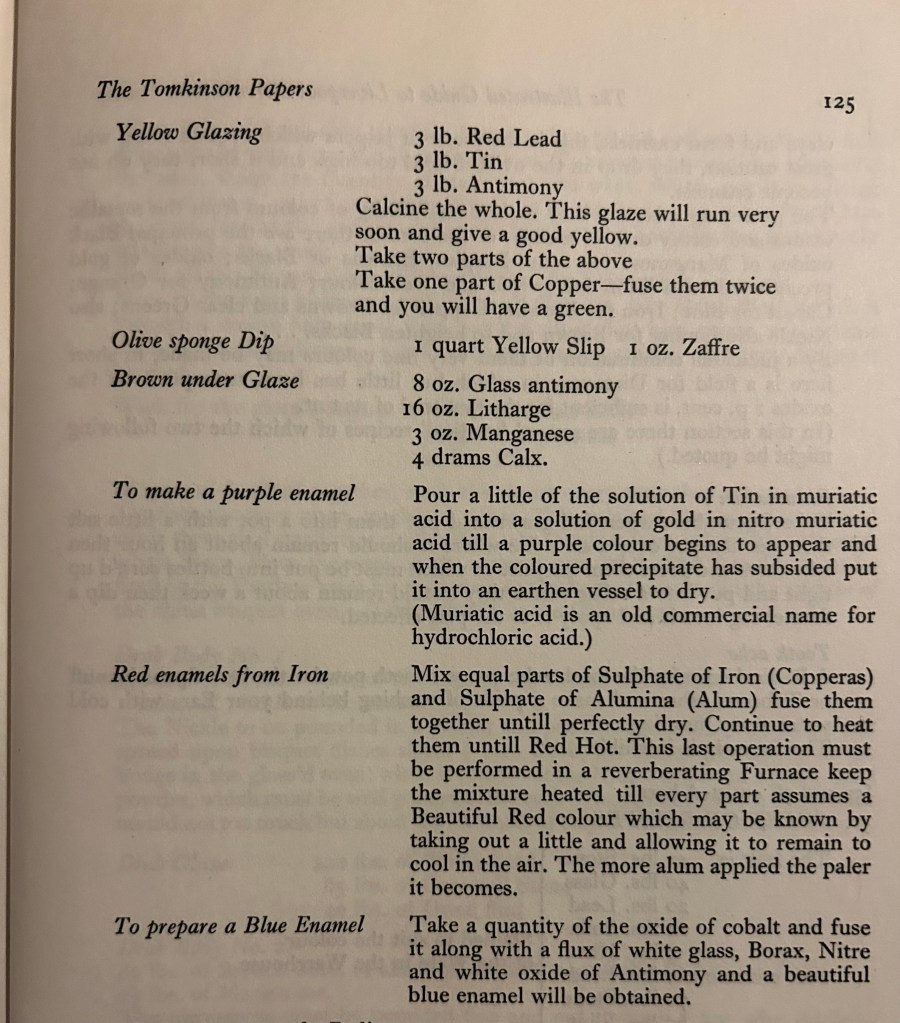

The chemical recipes for several colours were written into a notebook in a collection of papers from Herculaneum (and I assume John would also have had the skills to mix them himself):

Only the finest and most expensive ceramics were hand-enamelled — with purely decorative items such as John’s plaques at the most luxurious end — whereas more humble wares would have been transfer-printed. Shaw’s History of the Staffordshire Potteries, published in 1829, tells us that the art of enamelling initially developed separately from the potteries, particularly in tile production. At first it was simply an application of a white glaze, but over time the demand grew for ‘ornamented productions’ and consequently ‘a few of the more opulent [pottery] manufacturers’ brought the skills in house.

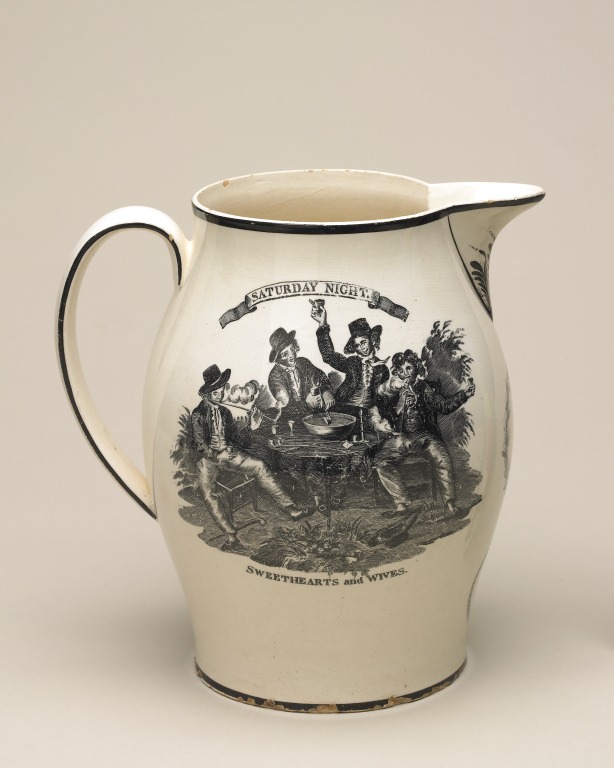

Where did John Edwards learn such an intricate and refined craft? Another item in the collection of the Museum of Liverpool is connected with an intriguing testimonial about his training. It’s a creamware jug made in about 1800, decorated with a scene of sailors making merry on Saturday night while toasting their ‘sweethearts and wives’ (it’s not clear if some sailors had both!). This lovely piece, which was last exhibited in 2015, belonged to John Edwards (and is therefore believed to have been made at Herculaneum) and was passed down in his family, eventually being gifted to the museum by Miss Diane Edwards of Widnes, Lancashire. According to Diane, John had been apprenticed to Flaxman at Etruria before leaving Staffordshire for Toxteth.

©National Museums Liverpool, Walker Art Gallery

The Etruria Works in Hanley was the ceramics factory of Josiah Wedgwood, in Stoke on Trent (the location also tallies with his residence when he married in 1796, and the baptism of his children Margaret and James Hardy in 1798/1800). It opened in 1769, and produced Wedgwood’s fancier wares (the previous factories in Burslem continued to make more useful objects). John Flaxman was Etruria’s most famous designer, as well as being a celebrated sculptor (mainly of funerary monuments), draftsman and book illustrator — all despite fragile health due to a curved spine. John would likely have been apprenticed to Flaxman from about 1787-1794*, mastering his trade before marrying Mary in 1796. He perhaps then worked at Etruria until moving to Liverpool.

*Unfortunately there’s no record of John Edwards’ apprenticeship in the apprenticeship books that record stamp duty paid from 1710-1811 (The National Archives series IR 1) or in Staffordshire’s apprenticeship names index (which is mainly pauper apprentices). Perhaps there are some answers in the V&A Wedgwood Collection Archives in Stoke on Trent, which include some articles of apprenticeship, or in Newcastle-under-Lyme’s Guild apprentice records. I think it’s likely that his apprenticeship was funded by charity. More research is needed!

John Edwards may have technically been an enameller but he was also considered one of Herculaneum’s small number of ‘painters’. A factory minute book shows that in 1822, a gilder called Jesse Taylor was appointed as the ‘foreman of the painters’, with a salary of £2 10s. per week. John Edwards is one of four painters at Herculaneum that have been identified, and I assume that he would have been among the most well paid and respected potters.

In about 1820, a list was made of ‘persons to be engaged’ at the pottery, suggesting that the potters were contracted year by year. According to this list, John Edwards was to be assigned to Coffee Pots! If this was my John, it is hard to know if this was a desirable role or a demotion. Although only in his forties, it’s possible that he was in poor health at that time.

Life at Herculaneum

What was it like to live and work at Herculaneum? As Hyland points out ‘the joyous events which marked the opening … should not disguise the fact that work in a busy pottery around 1800 was both dirty and dangerous’ and that due to the risks from machinery and toxic materials, ‘potters everywhere were not long lived’. Chronic silicosis, dubbed ‘potter’s rot’, was the results of prolongued exposure to flint dust; it caused serious breathing problems and even blue skin, and it also made potters more susceptible to tuberculosis.

Nevertheless, Worthington seems to have been a considerate owner for the period. Many of the workers could rent cottages with scenic views across the water, and the management provided rewards and incentives for good work, a financial safety net for poor employees, a Sunday school and monetary support for a local free school. The Pottery also had a Benefit Society, established in 1804, which put on monthly social events and helped pay for burials. In 1813 the town was illuminated to celebrate the defeat of Napoleon, and the men at the Herculaneum works were all treated to bread, cheese and ale. Herculaneum’s proprietors also built a small Methodist chapel for the workers, since many of the families from Staffordshire were Wesleyans. A chapel account book from 1815 includes expected expenses such as bibles and sacramental wine, as well as haircutting, boat hire, leeches, and a ‘lovefeast’ (the mind boggles!!)

In 1815 the area also gained a new Anglican church, St Michael in the Hamlet in Aigburth (originally built as a chapel-of-ease to the church at Walton on the Hill). In keeping with the industrial innovation of the time and place, it was one of the first buildings in the world to be constructed using cast iron. The first service held there was one of Thanksgiving for the victory at Waterloo. The community at Herculaneum was extremely tight-knit, and the parish registers of St Michael’s are full of the same names; ‘there was evidently much intermarriage between the families forming the Pottery community.’ The Liverpool historian J A Picton wrote that the Herculaneum potters ‘long continued a separate and isolated people, preserving their own manners and customs and still retaining their Mercian dialect’. The location of the pottery, in an extra-parochial and sparse area outside of the town, would have contributed to this strong sense of community. A newspaper announcement of a ‘match of the athletic game of prison-bars’ (a bit after John’s time) shows that the ‘potters of the Herculaneum Pottery’ had a distinct identity, but they weren’t cut off from the town, and they were able to have some fun!

The Edwards family: potting connections

Following the birth of Ann Edwards in 1802, John and Mary had four more children in Liverpool: Isaac (1805), Aaron (1807), Elisha (a boy, 1812), and lastly Emma (1815) — my husband’s 3x great grandmother. The baptism registers consistently record John’s occupation as simply ‘Potter’. Unsurprisingly, John and Mary’s children, and grandchildren, maintained strong connections with Herculaneum and the pottery trade:

- Margaret Edwards married George Ibbs, a potter, and they lived in the Herculaneum Pottery. The Ibbses were an important Herculaneum Staffordshire family. In fact, 14 members of the family were early potters at the factory and one of them later ran the biscuit factory (as in biscuit ware). Tragically, Margaret buried her husband less than a month after they baptised their first and only child, George, and then young George died at the age of 3. More than a decade later Margaret remarried to Henry Byram, a shipwright (not a surprising occupation for Liverpool, but an outlier in this family!). But despite being 16 years her junior, and safe from the hazards of the pottery, he died after just three years of marriage. He was buried in the Wesleyan cemetery.

- James Hardy Edwards married Rachel Roberts, the daughter of Edward, in 1822. Edward Roberts must have one of those first ‘migrants’, because he is the potter who produced that pioneering chamberpot! When James married, he was a potter, but in the 1841 census, he was an ‘Accountant’, and there’s evidence to suggest that he was the Manager of Herculaneum in the mid 1820s! This was noted by Peter Entwhistle, Curator of the Mayer Collection in the Liverpool Museum in the early 1900s. Unfortunately, few Herculaneum records survive from the 1820s as many were destroyed in the Blitz, so this can’t be verified. James must have been a prominent member of society as he served as Secretary of the Liverpool Dispensaries. In 1834, James was elected as Governor of the Workhouse, with Rachel becoming its Matron. He died in 1845.

- Isaac Edwards married Ann Roberts, another daughter of Edward, in 1835, and they immediately moved to Burslem, where Isaac worked as a potter. After a few years in Bovey Tracey in Devon, they returned to Staffordshire. By 1861 Isaac was a Commissioners Agent and by 1871 a Pottery Manager. Some of their 14 children were also potters, including Lawrence, a pottery figure maker.

- Ann married Edward Roberts, a potter, in 1823 at Walton on the Hill. I think it’s very likely he was the son of Edward ‘chamberpot’ Roberts. Edward Jr. died in 1844, and in 1851, Ann was a widow living in Hanley, Staffordshire. Her daughter Ann, aged 20, was a potter. Ann Sr’s twice-widowed sister Margaret Byram was also living there, and also worked as a potter. It’s important to remember that many women worked in the potteries. As Michael Sharpe writes in Tracing Your Potteries Ancestors, ‘The pottery industry was unusual for the period in that men and women worked alongside each other. Women generally had the lighter but less agreeable work.’ In one Staffordshire pottery in the early 1840s, 45% of the 348 employees were women and girls (the industry also employed large numbers of children).

- Sadly, Aaron Edwards died at the age of 20 in 1827 and Elisha aged 16 in 1828. Their burial records at St Michael’s state that their abode was ‘Pottery’. Whether they worked there as well isn’t recorded, but it’s highly likely.

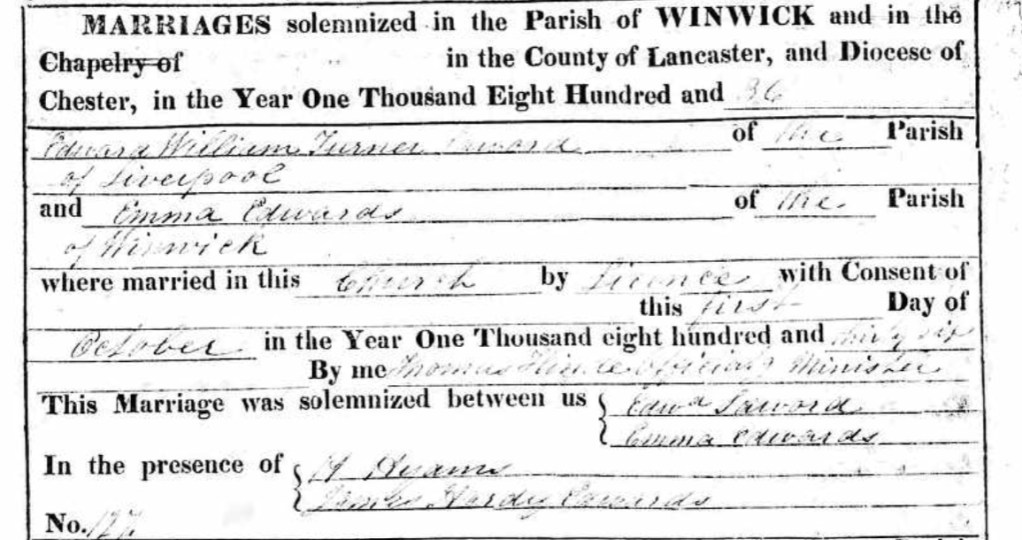

- Finally, Emma Edwards, my husband’s direct ancestor, married Edward William Turner Saword in Winwick, her parish of residence, in 1836. Edward was a Greenwich-born merchant based in Liverpool. Winwick is nearly 20 miles from Liverpool, and as far as I’m aware Emma wasn’t a potter. None of Emma’s children or descendants were potters either, but thanks to James Hardy Edwards’ signature as a witness in the marriage register, I can be certain that she was the daughter of John and Mary Edwards of Herculaneum. Since confirming her parentage I’ve also identified the person who registered her death in 1849 as her sister, Margaret Byram of Hanley, who I now know worked as a potter. Very sadly, no beautiful (or even plain) potterywares have been handed down in the family!

Potters turned to clay

In 1824, the Herculaneum Benefit Society purchased a small parcel of the churchyard of St Michael in the Hamlet, enough space for seven burials. The ‘potters’ grave’ is marked by a stone tablet on the ground near the vestry door, inscribed with the following touching verse:

Here peaceful rest the POTTERS turn’d to Clay

Tir’d with their lab’ring life’s long tedious day

Surviving friends their Clay to earth consign

To be remoulded by a Hand Divine.

John Edwards was laid to rest at St Michael’s on 1 April 1825. He was 51. His wife Mary was buried there on 10 April 1840 and their eminent son James Hardy in 1845. Mary, James Hardy, Aaron and Elisha share a ledger stone. A free burial index for the church shows that 16 burials of an Edwards took place between 1821 and 1865. At 68, Mary Edwards was the longest-lived. There were also numerous marriages, and 23 baptisms all the way up until 1908. The later generations of the Edwards family may well have attended a major historical exhibition that was held to celebrate Liverpool’s Sept-Centenary Anniversary in 1907. Both of John’s plaques were displayed alongside some ‘papers by John Edwards, relative to the establishment of the Herculaneum Pottery’. These papers were owned by Jaggard & Co, a Liverpudlian bookseller and printer. I would love to know if the papers have survived somewhere! However, knowing that they existed is confirmation enough that John was a key member of the Herculaneum pottery from its earliest days. It must have made his descendants very proud.

The Herculaneum Pottery continued in production until 1840. Unlike the sudden destruction of the ancient city of Herculaneum, there was no cataclysmic event that brought production to an end. Rather, the business changed hands a couple of times, and finally wound down. The land was later used as Herculaneum Dock (until 1970), and the site is now occupied by small industrial units and a business park. The last potters’ houses were pulled down in the 1960s. Only a local pub, the Herculaneum Bridge Hotel, hints at the behemoth of a pottery works that was once an almost self-contained community of hundreds of people, and sent its wares all over the world.

Acknowledgements

My sincere thanks to Nicola Scott, Curator of Decorative Art at National Museums Liverpool for providing images of John Edwards’ ceramics and additional insights into his work.

Select sources/Further reading

Peter Hyland, The Herculaneum Pottery: Liverpool’s Forgotten Glory (National Museums Liverpool and Liverpool University Press, 2005) (a digital version is available to ‘borrow’ at archive.org)

Alan Smith, The Illustrated Guide to Liverpool Herculaneum Pottery (Barrie & Jenkins Ltd, 1970)

Michael Sharpe, Tracing Your Potteries Ancestors (Pen & Sword, 2019) (this book is focused on the Staffordshire potteries)

Joseph Mayer, On Liverpool’s Pottery [available to read online] (1855)

Useful resources

Staffordshire Name Indexes: free access to 26 indexes to the holdings in Staffordshire Archives, including illegitimacy, apprenticeships and asylum patients

Liverpool as a Trading Port Project: free database of 1.3M individual life records and 33k voyages to and from Liverpool

OnLine Parish Clerks for the County of Lancashire: free index to baptism, marriage and burial registers by parish

thepotteries.org: website about the Staffordshire potteries, with an A to Z index index of pottery works, guides to ‘how it was made’, pottery terms, pottery occupations and much more

One thought on “A Herculaneum Potter”