Lucy Worsley’s new podcast series, Lady Swindlers (which follows two series of Lady Killers) looks at the lives and crimes of some notorious female criminals and con-artists in the UK, America and Australia. Inspired by their stories, I decided to revisit an old blog with a fresh perspective. Back in 2020 I published a detailed account of the life and career of George Read, a self-made Detective Inspector with the Metropolitan Police Thames Division who served from 1855-1888. Detective Read tackled crimes committed on or next to the River Thames, most in East London. Among the many shady, cunning or just desperate characters who’d crossed his path were three women. Now, I wanted to see if I could find out more about them.

Please note: I’ve transcribed full news articles in this blog, as I find them absolutely riveting. But if you’re short on time, I’ve highlighted some of the juciest bits in bold.

First up, we meet ANN GILLIGAN, a habitual offender whose house was ‘a nursery of crime and dissipation’. An article from the Morning Advertiser describes her trial on 13 September, 1870:

POLICE COURTS.

THAMES.

IMPORTANT CONVICTION FOR SELLING BEER AND SPIRITS WITHOUT A LICENCE. – Ann Gilligan, aged 38 years, was brought before Mr. Lushington, charged with illegally selling beer and spirits without a licence on Saturday night, by which she had incurred a penalty not exceeding 100l.

George Marsden, a Thames police-constable, No. 190, stated that on Saturday night, at half-past twelve o’clock, he was on his way home with another constable, when they were accosted by two prostitutes, who asked them to treat them to drink. He said it was too late, as all the public-houses and beer-houses were closed. The women said that was no matter, as they knew a place where plenty of gin, rum, and beer could be obtained. They accompanied the women to the house of the prisoner, No. 2, Angel court, Shadwell, where they saw eight or nine men and women drinking gin and beer supplied by the prisoner, who took the money for the same. They were supplied each with a glass of gin, for which the prisoner charged 3d. per glass. He and his brother constable then had a pint of beer, for which 3d. more was charged. He complained of the price, and the prisoner said, “Recollect it’s after hours—you must expect to pay a little more.”

George Read, Inspector of the Thames Police, said he went into the prisoner’s house after the last witness left it, and there found in a drawer four bottles—two containing rum and two gin. He also discovered two casks of beer under a box, and seized the whole. Inspector Rouse, of the K division, said the prisoner had been in custody for every offence in the statute-book, not even excepting murder, and had been convicted many times. She had recently come out of prison after a nine months’ sentence. for an offence under the Habitual Criminals Act. He had received innumerable complaints of the prisoner carrying on an illegal traffic in beer and spirits, but he could not detect her. Sailors had been inveigled into her infamous house, made drunk, and stripped of all they had. At last he consulted with the Thames police, and a ruse suggested by Inspector Read proved successful.

The prisoner, in defence, said she never sold anything. She expected five sailors home from the ship Ocean Maid, and provided some gin, rum, and beer for them. Some friends brought in two men, and she gave them a little gin and beer.

Mr. Lushington said he had no doubt whatever that the prisoner had been for some time, and habitually, carrying on the illegal traffic in gin and beer and other liquors, and that her dwelling was the nursery of crime and dissipation.

He fined her 50l., which was half the maximum penalty, and in default of payment three months’ imprisonment and hard labour.

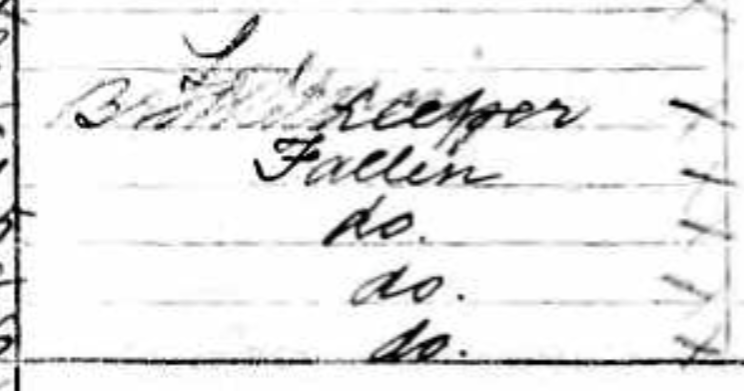

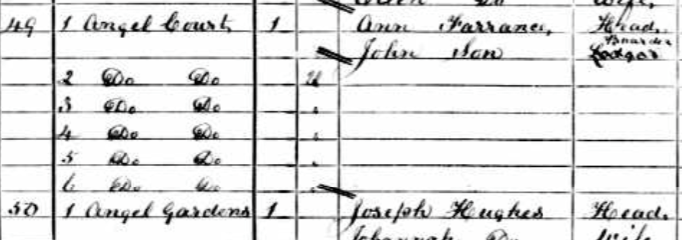

I was able to find ‘Ann Galligan’ in the 1871 census (seven months later), still at 2 Angel Court in the parish of St Paul Shadwell (Tower Hamlets). Ann, 38 and unmarried, clearly felt she had nothing to hide, as her occupation is recorded as ‘Brothelkeeper’, and her four female lodgers (Catherine Sullivan, 30, Ann O’Brian, 25, Annie Learey, 28, Mary Ann McGinnis, 28) had the occupation of ‘Fallen’! All of them came from Ireland. The household that night also included three single male lodgers, who might have been clients. Lastly, there was a female servant from Hull.

None of their immediate neighbours reported being engaged in sex work. They included a costermonger, shoe black, labourer, sackmaker and even post office telegraph. However, that the neighbourhood was poor is clear from the records two doors away of two beggars from Bombay, described as ‘black men’. One was called ‘Sick Abraham’ and the other ‘Niel Niger’.

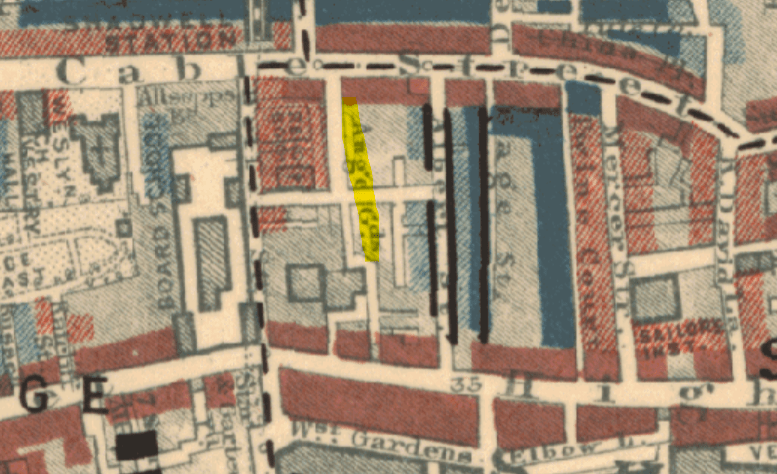

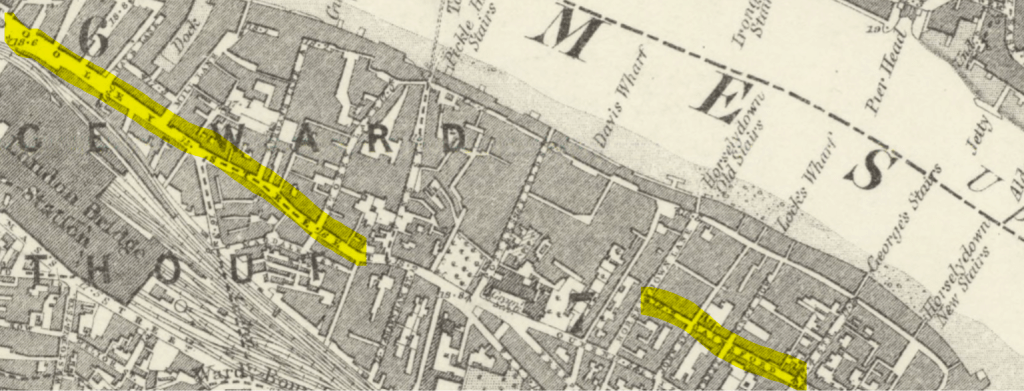

I’ve studied several street maps from around 1870, as well as Charles Booth’s ‘Poverty Map’ of 1889, and none show Angel Court. However, I know that it was located between Cable Street and Shadwell High Street and was enumerated in the census right before Angel Gardens, which I have highlighted in Charles Booth’s map below. Parallel to Angel Gardens was Albert Street, which was rated ‘black’ — defined as ‘lowest class, vicious and semi-criminal’. The enquiry’s police notebooks described the street: ‘women ragged, several brothels, children dirty ragged hatless, one only shoeless.'(1) Of the 30 houses on Albert Street in 1871, almost every single one was a ‘bad house’, inhabited by ‘fallen’ women and sailors. A National Archives blog looks at another very similar Shadwell street in the same census ‘Piece’ in 1871: Albert Square.

A more detailed OS map surveyed in 1862-73 reveals a number of unlabelled narrow courts and passageways between Angel Gardens and Albert Street, which must have included Angel Court. The Thames Police Court on Arbour Street was less than half a mile away.

Excerpt from Maps Descriptive of London Poverty from Charles Booth’s Inquiry into Life and Labour in London

https://booth.lse.ac.uk/map

It’s a shame that the court registers for the Thames Police Court (Magistrates Court), in the London Archives, only go back to 1881. However, one criminal record that could well be for Ann, is in the Quarterly Returns of Prisoners in Hulks and Convict Prisons, June quarter, 1861. Specifically, Ann Gilligan was an inmate of the Female Convict Prison in Brixton — Britain’s first women’s prison. She was 27 and had been sentenced for three years for the offence of ‘Larceny [against a] person’ in Westminster, August 1859. Her behaviour that quarter was ‘Good’ and she was moved to Fulham on 18 June 1861.(2)

Another likely record for Ann is in Middlesex House of Detention Calendars (found in The Digital Panopticon) in 1868. The House of Detention was built in Clerkenwell in 1847 and held prisoners awaiting trial. Said to be 34 and married, with ‘imperfect’ literacy, Ann Gilligan was accused of stealing a coat and a handkerchief (value 20s., the property of William Emsley), and tried on 31 August 1868 for larceny and receiving after a previous conviction. However, she was acquitted.

A search for Ann in London’s Morning Post located a report on the trial that had sent Ann to prison under the Habitual Criminals Act. According to this article of 22 October 1869, hers was the first case of its kind — the charge being that she was allowing thieves to gather in her house — to be prosecuted under the act. Bizarrely, she was described as an elderly, white-haired woman, although if her age in the 1871 census is to be believed, she was only in her late thirties.

THAMES.

THE HABITUAL CRIMINALS ACT.-A NEST OF THIEVES

Ann Gilligan, an elderly women with white hair, was summoned before Mr. Paget, under the 10th clause of the Habitual Criminals Act, with knowingly permitting and suffering thieves to meet and assemble in her house. This was the first case of the kind presented under the new act, which in likely, it rigidly enforced, to be productive of immense good to the public. The 10th clause of the Habitual Criminals Act applies to “every person who occupies or keeps any lodging-house, beer-house, public-house, or other place where excisable liquors are sold, or place of public entertainment or public resort.” The prosecutor in this case was Inspector Rouse, K division, who proved by the evidence of Stimpson, 21, Cox, 45, and Smith, 47, sergeants of the same division, that the prisoner kept an “abominable den,” as it was termed by the magistrate, at No. 2, Angel-court, Shadwell, where robberies and outrages of every description had been committed; that she cohabited with a notorious thief, named William Scott; that both had been frequently convicted of felony; that she was once sentenced to three years’ penal servitude: on her release she recommenced her career of crime; and on one occasion she was charged with murder under circumstances of grave suspicion, but the case failed and she was discharged.

Johanna Hayes, one of the defendant’s lodgers had been lately convicted of a robbery committed in her house, and sentenced to 18 months’ imprisonment and hard labour, and Ann Craven, another of her lodgers, was, after repeated convictions for felony, convicted for wilfully breaking a pane of glass value 4l., in the house of Mr. Stephenson, a licensed victualler, and sentenced by Mr. Paget on Saturday last to two months’ imprisonment and hard labour. On the last visit of the police to the house they found Scott, the defendant’s paramour, and several other thieves assembled there. It was the worst house in the district. On Saturday night and Sunday morning, while the licensed victuallers’ houses and beer-houses were closed, spirits and malt liquors were sold there to the prostitutes and thieves of the district. The defendant, in reply to the charge, said she did not keep a lodging-house as charged in the summons, but that she kept a common brothel, in which two women of loose character were lodging, who frequently brought home strangers who paid her for temporary accommodation. She certainly cohabited with Scott, who was a thief, and she was one herself, but there were many others just as bad. She attributed this prosecution to vindictive motives on the part of Stimpson, because sbe refused to divide 10s. with him, which she received from the captain of a ship for the restoration of his papers. This charge was investigated, and found to be totally unfounded.

Mr. Paget said he had no doubt whatever of the vile character of the prisoner, and that her abominable den was the harbour of thieves and reputed thieves. He knew that frequent robberies and outrages had taken place in her house; that she and her paramour were thieves; and that her house was an abominable den of infamy and crime. The only thing he had been in doubt about was whether a brothel was a lodging-house. He reviewed the history of the defendant’s house and the purpose to which it was applied, and said that on reading the definition of a lodging-house in the Common Lodging-houses Act, he was satisfied that her dwelling came under the definition of a lodging-house. He convicted her in the full penalty, 10l., and in default of payment he sentenced her to be imprisoned and kept to hard labour for two months, and to find sureties in the sum of 20l. to keep the peace, and be of good behaviour for six months. The prisoner was committed.

I love the way that Ann brazenly said that she wasn’t running a lodging house; she was just running a brothel! However, it’s useful to have some historical context about the legality of sex work and brothel-keeping in this period. Prostitution was then, as now, not a crime, albeit viewed by many in society as immoral. However, in the 1860s, sex workers were targeted by several Contagious Diseases Acts, which empowered police to arrest and detain women suspected of having venereal diseases. These acts were still in force in 1870 (they were repealed in 1886). In 1870 it was also legal for Ann to run a brothel; her business would not be threatened until the Criminal Law Amendment Act of 1885, designed in part to suppress brothels.

So, Ann was not committing a crime by running a brothel. However, she also admitted, without qualms, that she was a thief, as was her partner, but argued that they were no worse than plenty of others! But it was Ann’s role as a lodging house keeper that was finally landed her in gaol. It was clear that she was enabling criminals to convene at her house. So, Ann was sent to prison as a habitual offender, but we know that this spell behind bars did nothing to make her change her ways.

Given that Ann was said to have been ‘convicted many times’, and even charged with murder, we would expect to find many more records and reports of her crimes and punishment. There may well be a treasure trove of evidence to be found in archives. The next time I visit the National Archives I’ll take a look at the Habitual Criminal Register (PCOM 2). However, another newspaper article from more than a decade earlier reveals one reason that Ann might have eluded records: she had at least one alias.

In the Morning Advertiser, 6 August 1859, a story titled ‘A FOOL AND HIS MONEY’ described a theft of banknotes and sovereigns committed by a group of five women. The victim, Mr Christopher Schnackenberg of Stepney, had been on his way to deposit the money in the bank, when he was induced to enter a pub, and ‘being a little the worse for liquor, treated a most infamous woman, named Gilligan, alias Hall, now under remand, with gin.’ Several women then led him to ‘one of the worst places in the district, Angel Court’, where he was hustled and robbed. Poor Mr Schnackenberg.

At the Thames Police Court, two of the women — Catherine Dwyer alias Devine, and Mary Ann Birkett — were brought before the judge. But a witness who knew the accused women gave evidence that Dwyer “was not in the robbery at all. It was her sister, Sir, Ann Gilligan alias Hall, was the principal in the robbery.” It seems that Ann was the ringleader of this female gang, unless, of course, her present incarceration made her an easy scapegoat.

I wondered if I could find out anything about Ann’s early life and I discovered that she might have come to London as the daughter of an Irish Private in the British army. In 1841, an Ann Gilligan aged 10 was living in Deptford Barracks with her soldier father, Joseph, her mother Julia, and a younger sister Margaret. Ann and her parents were all born in Ireland, and Margaret, aged 3, in London, which suggests that the family had come to London in about 1837.(3) However, a brief search for her in the 1851 and 1861 censuses of England drew a blank.

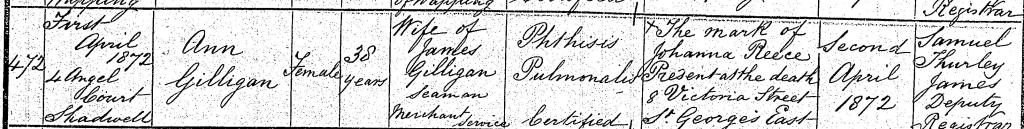

Ann’s criminal career did not carry on for long after Inspector Read’s ruse led to a conviction; her death was registered exactly a year after the 1871 census. She died on 1 April 1872 at number 4 Angel Court in the presence of Johanna Reece, who lived on neighbouring Victoria Street. The cause of death was ‘Phthisis Pulmonalis’ (TB), and she was still said to be 38. When Johanna registered the death, she claimed that Ann was the wife of James Gilligan, a merchant seaman. Was Ann really a married woman who ran a brothel while her husband was away at sea? Or had her neighbour chosen to give her a more socially acceptable identity?

After Ann’s death it seems likely that 2 Angel Court continued to be a ‘nursery of crime’, and a place law-abiding people avoided, as in the 1881 census, the entire street, except for number 1, was left blank.

The next ‘lady criminal’ I investigated was MARY JONES, a ‘masculine-looking’ smuggler who specialised in hiding contraband in her purpose-made petticoat. The following report was made in the Morning Post on 30 August 1879:

POLICE INTELLIGENCE

THAMES

Mary Jones, 50, a tall, masculine-looking woman, was charged with carrying and conveying 16lb. of compressed foreign manufactured tobacco, the same being liable to duty. Detective-sergeant Howard, of the Thames Division, stated that the previous afternoon he saw the prisoner in the Commercial-road. Knowing the character she bore, he followed her for some distance, watching her clothes, and at length, being satisfied by their appearance thas she had something about her, he stopped her in Three Colt-street, Limehouse, and asked if she had anything about her that was liable to duty. She professed to be very indignant, and said that she had not. Witness however, took her to the Arbour-square station, when the female searcher was fetched to her. Defendant then, in the presence of Chief-Inspector Steed, produced a quantity of cakes of compressed tobacco, amounting in all to 17lb. These cakes she bad slid into a number of slits in a heavy quilted petticoat she was wearing, and which had evidently been made for the purpose of conveying smuggled goods.

Detective Inspector Read, of the Thames Division, said that he knew the prisoner, who resides at Gainsford-street, Horselydown, as a regular old smuggler. She had been previously convicted, but he was not then prepared to prove the conviction. She was in the habit of collecting the goods from persons who managed to bring them from abroad, and then disposing of them here. It was through the inducements held out to them by such persons as the prisoner that sailors and others carried on smuggling to such an extent. The single value and duty of the tobacco found on defendant was £4 10s. 8d. Inspector Woodley said that prisoner had £17 in cash on her when she was charged.

Mr. Lushington fined defendant treble value and duty, viz., $13 12s., or in default one nonth.

Defendant said she would not pay it, and was then removed.

(As a slight aside, I found it fascinating that the police had a ‘female searcher’ to search Mary for contraband, and would love to know more about that woman as well. A book on this subject, The Mysterious Case of the Victorian Female Detective, was published by Dr Sara Lodge just last month!)

I was able to find another report on the same case, in the Southwark and Bermondsey Recorder, a week later (6 September). This one provided an exact address for Mary:

A ST. OLAVE’S FEMALE SMUGGLER

At the Thames Police Coart, on Friday, Mary Jones, living at 2, Tooley Street, was charged wilh smuggling a quantity of tobacco.

James Howard, a Thames Police sergeant said that at nine o’clock on Friday morning he followed the defendant from Horselydown to Three Colt Street, Limehouse, where he stopped her and found 17lb. of foreign manufactured tobacco ingeniously concealed about her.

Inspector Read, Thames Police, said the defendant was a most notorious smuggler and she had a petticoat specially made to carry contraband goods. On the last occasion the police seized two cwt. of tobacco in her possession, and she was charged at the Southwark Police Court, but he was not prepared to prove the conviction.

Mr. Lushington fined the defendant £13 12s., or, in default of payment, one month’s imprisonment.

The second article gives Mary’s address as 2 Tooley Street, whereas the first states she lived on Gainsford Street. Both are close to the river.

Frustratingly, I was not able to locate 2 Tooley Street in the 1881 census. And in a search for the name Mary Jones on Tooley Street, only one came up, at number 150, and she was just five years old. There was noone called Mary Jones on Gainsford Street. However, there were dozens of adult Mary Jones’s living in the parish of St Olave. Our Mary Jones was well-known to the Thames river police, and the newspapers give us a striking image of her appearance, but unfortunately, with such a common name, it is very difficult to link our Mary to any other records.

Our final female offender is MARGUERITE SHMYTHE, a German tobacconist with a business on West India Dock Rd.

POLICE INTELLIGENCE

THAMES

CHARGE OF SMUGGLING AGAINST A POPLAR TOBACCONIST. — Miss Marguerite Schmythe, a tobacconist, carrying on business at 94, West India Dock-road, was summoned at the instance of Mr. Starkey, of H.M. Customs’ Office, for “harbouring” a quantity of foreign manufactured tobacco and cigars, the same being liable to duty.—Mr. Beverley appeared in support of the summons, and Mr. Charles V. Young defended.—It appeared from the evidence that on the 2nd inst. Detective-inspector Read, of the Thames division, visited the defendant’s premises, in company with Detective-sergeant Horlock. On examining the place Inspector Read discovered 24lbs. of shag and 4lbs of Cavendish tobacco, which he at once detected by its appearance as having been packed in small parcels in the way this foreign tobacco is brought to this country. He also found 4lbs. of foreign manufactured cigars. When questioned as to where she had got these, the defendant stated that she had taken them in payment of a debt of 11s. that some woman, who lived in Leman-street, owed her. The tobacco had been bought of a man who lived with the woman in question, and she had given 3s. 1d. per lb. for it. Inspector Read seized the whole of the tobacco and cigars, and told the defendant that she would probably hear more of the matter.—Mr. Beverley said that the single value and duty would be £9 13s. 4d, but the Board elected to sue for the full penalty, viz, £100.—Mr. Younger cross-examined Inspector Read at considerable length, especially with regard to the fact of the tobacoo being of foreign manufacture. —The inspector said he had no doubt at all aboat the matter. Tbe tobacco he seized had the “knotty” appearance which tobacco that had been compressed and packed in small parcels always had; besides, when he seized it, the tobacco was moist and warm. this evidently being due to the fact of its having been “steamed,” a process that tobacco of that class was generally subjected to, so as to loosen it after packing, before it was sold. The ordinary duty would be 4s. 4d. per lb.—Mr. Young made an earnest appeal on behalf of his client, who, he said, was a German, and probably unacquainted with the laws. He ventured to submit that she had not been guilty of “knowingly harbouring” the tobacco. If, however, his worship thought there was sufficient evidence to convict the defendant on, he begged that he would exercise his discretionary powers given him by the Act, and reduce the penalty to the minimum amount, viz., £25, as the defendant was a femme sole and merely in a small way of business.—Mr. Saunders said that after the evidence he was bound to come to the conclusion that the Customs authorities had made out their case. He was forced to convict the defendant, but would give effect to what had been urged by her advocate on her behalf, and merely fine her £25. [East London Observer, 17 May 1879]

Unlike Ann Gilligan and Mary Jones, Margueurite Schmythe was addressed as ‘Miss’, so seems to have been viewed as more respectable than the those two women, and no mention is made of any previous convictions. Assuming that my ancestor Detective-Inspector Read really knew his stuff (or should that be his snuff?), and that she had indeed taken in goods that had evaded import duties, it would have been very daring of Marguerite to sell it openly, since Customs House was on the same street! It is possible that she was genuinely unaware that she had something wrong, as her legal representative asserted. He claimed that since she was a German she was simply unfamiliar with local laws. However, it was her status as a single woman (a ‘feme sole‘), just running a small business to support herself, that ultimately brought her some leniency from the magistrate … though £25 was still a considerable fine — about £2600 today.

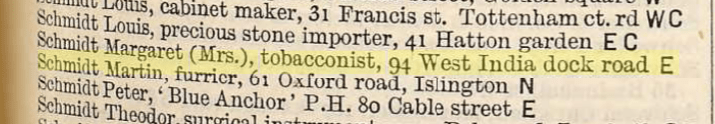

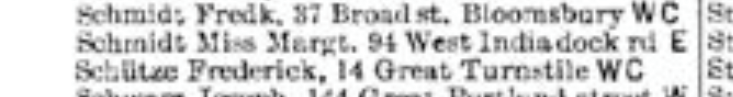

I was intrigued to find out whether Marguerite had been born in Germany, and when she had come to London. I suspected her surname would have been Schmidt, and this is indeed how it was spelled in the Post Office Directories of 1880 and 1882. I noted that in the earlier directory she was a ‘Mrs’ and later ‘Miss’. Her first name was given as Margaret.

Post Office London Directory, 1882 [Part 3: Trades & Professional Directory]; University of Leicester Special Collections

However, in the 1881 census, at the same address, she was recorded as ‘Magie Smith’, unmarried, and her birthplace wasn’t Germany … but Harrow.

Perhaps she had indeed been born in Harrow, but to German parents. I’ve found evidence for several women called Margaret Schmidt in London, including baptisms at Britain’s oldest Lutheran Church, St George’s in Whitechapel, that are just a little bit too early or late — but show that the name was being given by German immigrants to their London-born daughters. However, if Margaret had been born in England, it was a stretch to claim that she was not up to speed with the duties on foreign imports that she was selling in her shop. Perhaps she was not as innocent as she seemed.

Alternatively, could someone have misunderstood the place of birth she gave when the census was taken? In 1861, a 20-year-old woman called M Schmidt, born in Hesse-Darmstadt, was a domestic servant in Islington. Hesse does not sound very much like Harrow, but you never know!

A Margarethe Schmidt married hairdresser William Henry Hoflin in 1882; both Germans by birth, they settled in Hackney. And in 1884, Margaret Schmidt, daughter of Adolf but born in Marylebone, tied the knot at St Pancras. Did our Margaret Schmidt go from ‘femme sole’ [sic] to ‘femme mariée’?

Name spellings varied frequently in the 19th century and a foreign name was even more likely to be mispelled. Furthermore, many first- and second-generation immigrants adopt anglicised versions of their names, and often use both, choosing the one that best fit the circumstances. So, she could have been Margaret Schmidt in business, but Maggie Smith to her friends and neighbours. But it’s also possible that Margaret wasn’t German at all, and that she used the name Schmidt to conceal her true identity — a criminal alias, perhaps.

By 1891, the tobacconist shop at 94 West India Dock Road was in the hands of the Sutherland family. Had Margaret married? Returned to Germany? Or assumed another identity and carried on selling smuggled goods elsewhere? For now, Margaret Schmidt’s origins, and her whereabouts after 1881, remain a mystery.

- BOOTH/B/350; p207; https://booth.lse.ac.uk/notebooks

- Home Office. Prisons Correspondence and Papers, Series HO 20.

- Class: HO107; Piece: 488; Book: 5; Civil Parish: St Nicholas; County: Kent; Enumeration District: Deptford Barracks; Folio: 35; Page: 4