In this blog I’ll be sharing the experiences of a soldier whose WW1 service left him chronically unwell and unable to return to work.

When war broke out in August 1914, William Walter Talmer — an experienced member of the British Army Reserve (Territorial Force), was one of the first men to be mobilised. But two years later, William wrote desperately to the Middlesex Appeal Tribunal to request exemption from further service, which would “mean great hardship and loss”.

William — a cousin of my great grandfather Alfred Talmer — was born on 30 April 1886 in Amersham, Buckinghamshire. His mother Clara Jane Talmer was a single woman who raised William and his brother Sidney Ayers Talmer (b. 1893) alone, until she married James Keen in 1897. At the age of 14, in 1901, William was an apprentice blacksmith, but on 4 June 1903, claiming to be 18 years old (a year older than his real age), he enlisted at Oxford as a Private in the Oxford and Bucks Light Infantry. William’s extensive service records (which have been preserved within WW1 pension claims at The National Archives) state that he was a sawyer by trade (though he cannot have had much experience as a sawyer) and that he was 5 feet 6.5 inches tall, with light brown hair and hazel eyes. After two years in England, which included extra schooling, he spent more than six years with the Colours in India and Burma.

In the 1911 census, taken just two days after William returned from India, he was recorded as a 24-year-old Private staying in the home of his uncle in The Lee, Bucks. A month later, with eight years of military service under his belt, he transferred to the Army Reserve. William then began working at the Brentford Gas Works. The company had been founded in 1821, supplying 200 customers in its first year of operation, and by 1926 it provided gas for lighting and cooking for 124,000 customers. William’s job was to paint and repair gas stoves and cast iron work, skills he might have gained in his partial apprenticeship.

On 5 Feb 1912 William married Florence Margarette Nash at St Paul’s, Brentford. They welcomed a daughter, Emily Margarette, in 1913 and a son, Sydney Walter, in 1914. But family life was turned upside down on 4 August 1914, when Britain declared war on Germany. William, as an army reservist, was called up on 14 September, reported to his unit in Portsmouth and was deployed to France on 23 November as a Private with the Ox and Bucks 2nd battalion. This return to active service could hardly have come at a more difficult time for the family: Walter and Florence’s daughter had just had her first birthday, and their son was less than two months old. Even worse, Florence was chronically ill with Bright’s disease (an inflammatory disease of the kidneys now known as chronic nephritis).

William initially served in France for six months, although in December he spent time in a convalescent camp (reason unknown). Then, in May 1915, he sprained his ankle in action (possibly at the Battle of Festubert), and was transferred to hospital in England. Soon afterwards he fell ill with ‘gastritis’ and pain in his right side. He was at Emsworth hospital when the National Registration Act was passed on 15 August 1915. Despite still being unwell, he was drafted back to France in September, and served for another eight months. When he was discharged in June 1916, having served his full ‘period of engagement’, his military service was said to be ‘exemplary’ and he was described as ‘a thoroughly steady, sober and reliable man’.

William’s return to civilian life, and to his job at Brentford Gas Works, must have been a huge relief to his wife. However, William was not the man he was before the start of the War. A medical report reveals that after being discharged he was often unwell, was still having pain in his right side, and had to take days off work now and then. William might not have known it yet, but he had contracted tuberculosis. This highly contagious disease ‘thrived in the dirty and cramped conditions of trench life’1 and 55,000 British soldiers who served in the First World War returned home with the infection.2

In January 1916, the Military Service Act had introduced conscription in the UK, which meant that all healthy men between 18-41, except those in protected occupations of national importance, were considered part of the army reserve. Although William had already served his two years as a reservist with the regular army and had returned to his civilian job, he was potentially eligible to be called upon and sent overseas once again.

William’s efforts to support his family and to remain on the home front are revealed in a very moving 23-page file among the Minutes and Papers of the Middlesex Appeal Tribunal, 1916-1919 (within National Archives series MH 47). The tribunal was set up to consider appeals of men who put forward a case for exemption from military service. More details of the history and functions of the Central and Middlesex Tribunals are provided by the National Archives. William’s file shows that as well as suffering with an increasingly debilitating and potentially fatal infectious disease, he had to deal with the relentless bureaucracy of the war machine, and the continual push to do his patriotic duty.

On 7 December 1916, William applied to the tribunal for an exemption from service. He laid out four reasons, none of which mention his own health:

- “Having wife who suffers from Chronic Brights Disease“

Florence would have needed medical care, and William’s young family also depended on him not just financially, but for practical care. - “Eldest son of widowed mother with 3 children unable to work whom I generally give assistance“

William’s mother Clara had been widowed in 1913 leaving her with four children between the ages of two and twelve. The oldest was still just 16 in 1916.

- “Have served 13 years in H.M. Army 6 years 2 months in India & Burma 14 months in France. Have one brother in France one being called up in March.“

William makes the point that he has already given many years of service to his country, and that members of his family were also serving. It must have been William’s half-brother Sydney Ayers Talmer/Keen, aged 23, who was in France, possibly with the Honorary Artillery Company. His next oldest half-brother, Arthur James Keen, had recently turned 18, when he would have received his conscription draft. The absence of these young men, and their salaries, would have made their mother’s situation even harder.

- “Would mean great hardship & loss if called up again as I have lately purchased my house on installment system, and my home was broken up on mobilisation, my wife having to go home on account of illness, most of my furniture being spoilt.“

William had bought his house with a loan agreement. I’m not quite sure what that has to do with his home (i.e., his family life) having been ‘broken up’, or what exactly happened to their furniture after his wife went home (presumably to her parents), but it was clearly a very difficult time for the family.

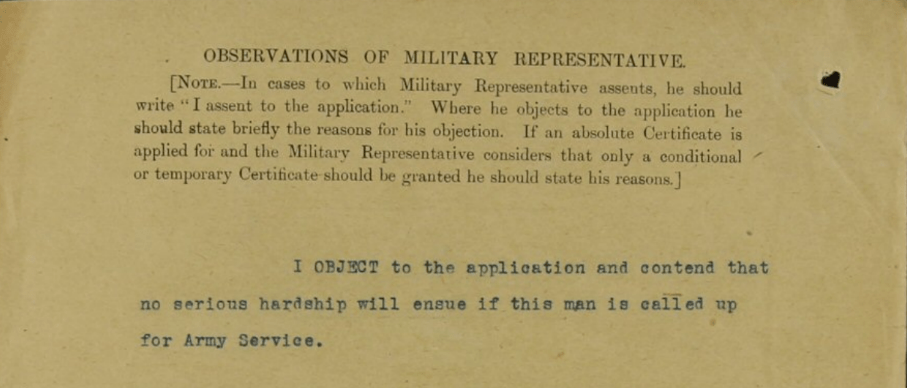

Five days later, a representative of the Military, having received a copy of William’s application, wrote to the tribunal to protest: “I OBJECT to the application and contend that no serious hardship will ensue if this man is called up for Army Service.”

Nevertheless, on 22 December the tribunal reached a verdict, and granted William an exemption until 22 April 1917, on the condition that he present himself at the Employment Exchange within 14 days to find work of ‘Essential national importance’. William had already returned to work at the gasworks, but this ruling would mean that he would have to leave his employment to find work that was considered essential to the war effort.

Once again, the Military contradicted the decision. A few days after Christmas, F J Chapman, a military representative from Drill Hall, Hounslow, wrote again to the Heston & Isleworth Tribunal to dispute the exemption. Chapman argued that William should be put to essential work immediately. “If he is exempted from Military Service I contend that his services should be immediately available for work of national importance.” This confusing communication suggests that during the four months of temporary exemption, William would have been able to continue to do non-essential work. However, Chapman pressed for him to do his bit for his country immediately. On 31 January William was called back before the Tribunal at the Guildhall, Westminster. His case would be heard at 2.30pm on Tuesday 6 February 1917.

Meanwhile, Brentford Gas Works contacted the Tribunal to make the case that William’s work was of National Importance: ‘‘He is engaged at these Works principally in carrying coke from the retort houses, and he is one of the few men left to us who is capable of such important work as coke-carrying, purifier changing, etc. Although Talmer was, on his discharge from the army last year, put to his old job in the stove-repairing and Cleaning Shops, he was some time back transferred to the Manufacturing side of the Works, where practically every man was badged by the Ministry of Munitions in 1915. We are toluol-washing and making shells on these works, and a large percentage of the gas and coke produced are consumed in Government and Munition Works in the 95 square miles of District supplied by us.”

In response to the Military’s demand for immediate patriotic work, and the Gas Works’ persuasive letter, the Tribunal amended the terms of William’s exemption: Firstly, he would have to continue in his current job (which they evidently agreed was of National Importance) or find another job of National Importance. A letter was sent to the Gas Works to advise them that if William ceased to work for them, it was their duty to report that to the tribunal promptly. Secondly, William would have to report every three months to the local military representative. However, since the Tribunal had determined ‘that it is expedient in the national interests’ for him to do work of national importance rather than be deployed again, he had won the right to remain on the Home Front.

Two days after the hearing, William saw a doctor at Hounslow Barracks, who found that William had not recovered from the effects of active service. He was categorised as C2, which meant that he was free from serious organic diseases, able to stand service in garrisons at home, could walk five miles and see and hear sufficiently3. However, a couple of weeks later, William was at work at the gasworks when he suddenly began coughing up blood, which lasted several days. After a few weeks in Hounslow and Hammersmith hospitals he was transferred to a sanatorium.

William’s gruelling job at the gasworks would have constantly exposed him to coal dust and chemicals, and the thought of him doing that work while suffering from a serious infectious disease in his lungs is very distressing. However, he had a young family to support.

On 26 June 1918, William wrote to the Tribunal from the Grosvenor Sanatorium in Kent. His letter reveals that he had been unable to appear in person (presumably at his three-month check-in with the Military Rep) due to being in an institution (i.e., TB hospital). As a result, the Tribunal was trying to remove his exemption. He assured them that he was willing to see the Medical Board (for an examination) providing he was fit to travel. I find it extremely sad that William was having to deal with such unfeeling red tape, while ill in hospital.

He wrote to the Tribunal again in about September to explain that he had been unable to do his job for six months due to pulmonary tuberculosis, and was no longer capable of doing the work he had done before the war. His doctors had advised him to find other employment. Ever polite and respectful, he asked the Tribunal to ‘vary his conditions’ again to allow him to do lighter work.

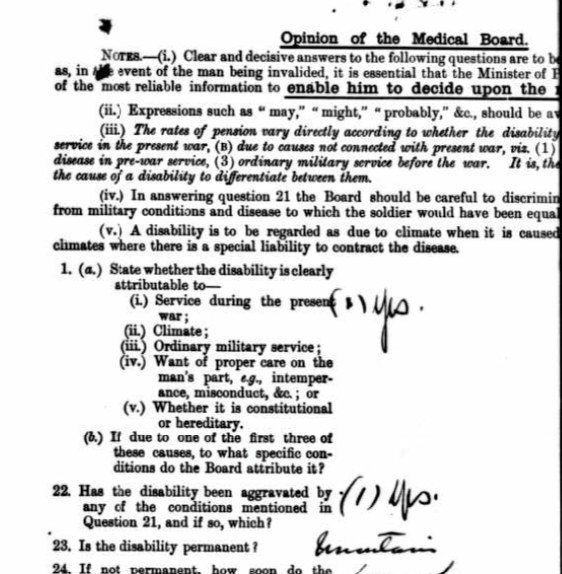

William underwent a thorough medical examination at Duke of York’s HQ in Chelsea on 22 October 1918. Although he was ‘a well developed man of good physique’, his degree of disablement was 30%. The medical officer in charge of his case wrote a detailed and very sympathetic account of William’s medical history since the start of his service in 1914, repeatedly stressing that he had carried out all his duties despite his illness. Critically, the opinion of the Medical Board was that this disability had been caused by service during this war.

In early October, the Tribunal consented to William finding lighter work of national importance. They instructed him that when he had found work, he had to submit to them for approval. Even with so many fit and healthy young men serving overseas, it can’t have been easy for William, who had limited civilian experience and education, to find a job that was considered vital and yet was not physically demanding. However, within just two weeks, William secured work at the Ministry of Munitions Aircraft Engine Instructional Works at Twickenham. He wrote again to the Tribunal for their approval. They approved — providing his employer could vouch for his hire and provide details of the work — noting on his letter, before filing it, that he was ‘tubercular’ and needed ‘lighter work than gasworks’. A copy of their decision was sent to the National Service Representative.

Exactly a fortnight later, Germany signed the armistice to end the war. William had made it through the ‘Great War’, and I hope he joined millions who celebrated in the streets across Britain and around the world. He certainly celebrated with his wife at home, because nine months later, William and Florence, despite their health problems, welcomed a third child, Vera Doreen Chester Talmer. At her christening, William gave his occupation as ‘Mechanic’.

William continued to have regular examinations with a medical officer. Although repeated laboratory tests found no TB in his sputum, in March 1919, William was granted a military pension for one year due to ‘tubercle of lung’. He still had a good colour and fresh complexion but was suffering from pain in his left side, shortness of breath, frequent coughing, poor sleep, and had experienced several bouts of haemoptysis (coughing up blood). His degree of disablement was now 50%.

Despite being seriously ill, he had been employed as a fitter’s mate on a tram car for three months. Perhaps the monthly allowance from the government meant that he could finally take some leave from work …

But I’m sorry to say that this story doesn’t have a happy ending.

William Walter Talmer died on 22 Jan 1920, aged 33, of ‘phthisis’ (TB), leaving behind his wife Florence and three children, the youngest still a newborn. His death was classified as a war death. Of the 55,000 British soldiers who came home with TB, 18,000 of them had died by 19224.

According to the Bucks Examiner, William was buried at Isleworth Cemetery ‘with full military honours’. He later received a war grave from the War Graves Commission (now CWGC).

Sadly, William and Florence’s oldest child, Edith, died later that year. She was only seven, and although I don’t have her death certificate I wonder if she had contracted TB from her father, making her another war casualty. William’s widow, Florence, moved to her parents’ home in St Albans with her two surviving children, and took on work at a silk mill. She only outlived William by seven years.

William is commemorated on Isleworth War Memorial, a large square stone clock tower topped with a wheel cross that was unveiled on 22 June 1922. Unfortunately his surname is mispelled as TALMERS W W. I was disappointed to find that he was not included on the memorial plaque for employees of Brentford Gas Works, perhaps because he had left the company for employment elsewhere before he died.

I am grateful to the Isleworth 390 Project, a community project to research the lives of 390 men and women remembered on the war memorial. A PDF about William Walter’s life shows his gravestone and his house at 25 Nottingham Road, Isleworth .

William’s brothers Sydney and Arthur survived the war, got married and lived long lives. However, two of William’s cousins, my great great uncles Harry and Charles ‘Charlie’ Talmer, were both killed in action in the summer of 1916. An ‘Honour Board’ at Lee Common School commemorates all ‘old boys from this school’ who served in the Army & Navy in WWI, including Harry, Charlie, and William Walter Talmer (mispelled ‘Talmar’).

The document images in this blog, unless otherwise stated, are from the following primary sources:

William Walter Talmer’s pension claim documents (including his service records): The National Archives, WO 364/4071; viewed digitally on pp4585-4606 of British Army WWI Pension Records 1914-1920, via ancestry.co.uk.

William Walter Talmer’s case papers (Middlesex Appeal Tribunal non-attested case papers): The National Archives, MH 47/54/51, Case Number: M2846 (digital download).

References:

- Philanthropy’s Fight Against Tuberculosis in World War I France, Rockerfeller Research Institute

- TB Hospital, Royal British Legion

- Recruitment to the British Army during World War I, Wikipedia

- TB Hospital, Royal British Legion

Edited Jan 2026 to include information about Florence after she was widowed (per 1921 census).

Thank-you for sharing this story and what a sad ending.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Fantastic, Clare.

You have found out so much about my Grampy’s cousin.

I knew he had died post war because of war related illnesses but nothing more.

It really is a very sad story and there must be many more of them, resulting from time serving in WW1.

LikeLiked by 1 person