You’ve heard the sassy song from Six, “Divorced, beheaded, died … divorced, beheaded, survived!” Well, this is my slightly less catchy version, with a military spin! In this blog I look at three men in my family tree who briefly served in the British army before leaving abruptly, probably without ever seeing action. Through a variety of records, I’ve learned about the causes … and repercussions … of their change of heart, I’ve discovered colourful physical descriptions of them as young men, and I’ve even found clues to their ancestral origins.

Case 1: Richard Maultby — Deserted

Richard, my 4x great grandfather, was born in Shrewsbury, Shropshire in 1814. His parents, Thomas and Anna, had a shop next to the Abbey Church. However, by 1828, and possibly as early as 1816, they opened a bakery in Leighton Buzzard, Bedfordshire, close to Thomas’s birthplace. Richard learned the family trade, but by the time he was a young man, something motivated him to exchange his white apron and baker’s hat for a green uniform and Baker rifle.

However, the lure of the army was short-lived. On 25 January 1832 Richard Maultby, aged 18, born at ‘St Chad’s, Salop’, appeared in a War Office list among dozens of military deserters in Hue and Cry (The Police Gazette). He had deserted from the Rifle Brigade in London, on 10 November 1831.

It’s always a delight to find any physical description of an ancestor, and thanks to Richard’s desertion, I know that at the age of 18 he was 5’9, stout, with square shoulders, a round head and oval face (not sure how that works!). His nose, neck, arms and hands, legs and feet, were deemed ‘prop(ortionate)’. He had light brown eyes, brown eyebrows, and a mole over his right eye. Most surprisingly, his hair was grey (or perhaps it was simply dusted with flour?)! When he had absconded he’d not been wearing regimental clothing — he was dressed in a brown coat and grey trousers.

It wasn’t uncommon to desert the army; Findmypast’s database of ‘Army Deserters 1828-1840‘ includes 34,000 records! Most of the men were young, and deserted within the first year, often the first weeks. I suspect this was the case for Richard. The punishment when a deserter was apprehended was typically flogging or branding, though I have no record of whether this was applied in Richard’s case. I do wonder where he went when he ran away. Did he go straight home? Many deserters returned to the army, and eventually got used to the regimented way of life, continual travel, and physical danger. But Richard returned to the family home, and to baking. And he proved to be an excellent baker.

Soon after his father’s death in 1838, he married Martha Hopkins, who joined the family business. His mother Anna was still head of the household and a baker in 1841, but after her death in 1847, Richard and Martha took over the Maultby bakery. In the 1851 census Richard was stated to be a ‘Master Baker’, implying that he had completed an apprenticeship. If he was formally apprenticed, it was probably with his father, though it seems likely he had not completed his training before joining the army. I hope to review Rifle Brigade musters and pay lists at The National Archives in the future, in case they offer more information about his enlistment and service.

Richard Maultby, one-time rifleman and long-time baker, died in 1866. But the Maultby baking dynasty continued for nearly 40 years after his death: Richard and Martha’s son William was a master baker in Leighton Buzzard, and their unmarried daughter Ann ran a bakery business in the same town until after 1901.

In 1914, another Richard Maultby enlisted in the army; Richard’s grandson and namesake Richard Maultby (b. 1871), served with the CEF in WW1. Richard, like his grandfather, found military service very challenging, and he faced severe discipline on multiple occasions. However, unlike his grandfather, he also faced brutal mechanised combat, and never came home again.

Case 2: Henry Saword — Defaulted

Henry Saword, my husband’s 2x great granduncle, was born in Hornsea, Middlesex in 1869, the third youngest of 18 children (12 surviving) of Edward William Turner Saword, a merchant. His mother was Edward’s second wife, Sarah Gibson. Within this huge family, Henry managed to carve his own path, showing an early talent for rifle shooting and interest in the military.

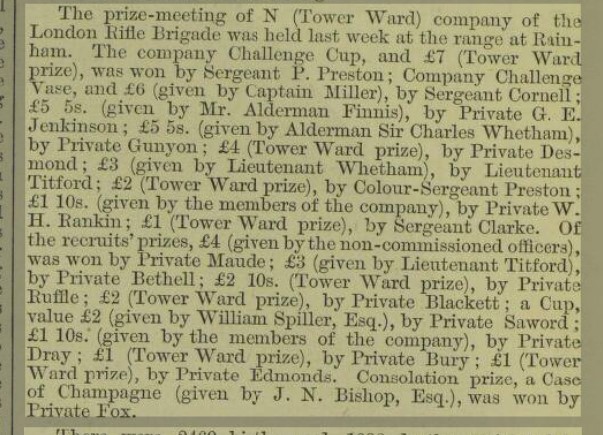

In 1877, as a new recruit in the volunteer London Rifle Brigade, Private Saword took part in a prize-meeting of the N (Tower Ward) company at the shooting range in Rainham (now a nature reserve), and was awarded a Cup, value £2. The Lord Mayor gave a speech at the prize presentation, and the Lady Mayoress distributed the prizes. According to the London Metropolitan Archives, who hold the brigade’s records, ‘The London Rifle Brigade was founded in 1859 and was the first City of London volunteer unit formed during that year. Its members were City clerks and City “men of good position”‘.

Image © Illustrated London News Group. Via britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk.

In the National Archives Discovery catalogue I found a reference to a document relating to Henry Saword, within a sub-series of ADM 157 (Royal Marines attestation forms), which included ‘attestations for ranks who were not allocated official numbers and served only for days or months’. Henry’s papers (ADM 157/647/400) were described as ‘Henry Saword, born Middlesex. Attestation papers to serve in the Royal Marines at Portsmouth 1880 (when aged 18). Discharged 1880 as Paid £10.’

Intrigued, I ordered the papers on a visit to TNA. Without expecting anything beyond an official form or two, I was pleasantly surprised to find a small set of letters and notes, which gave me a glimpse into an eventful few weeks in Henry’s youth, 140 years ago.

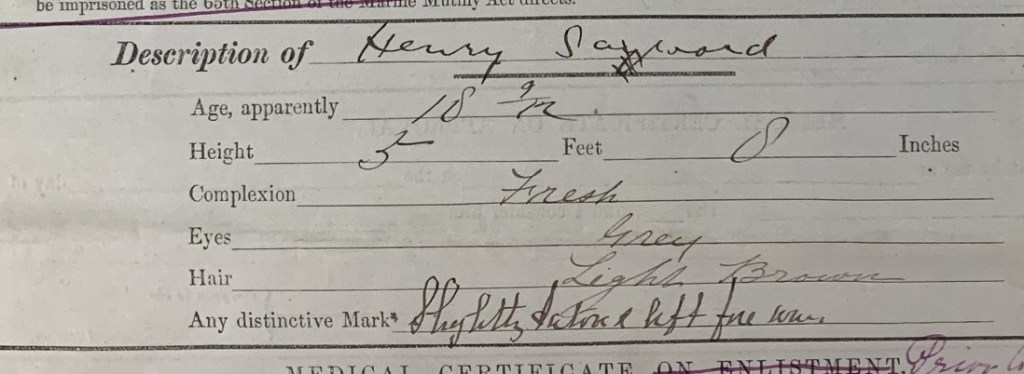

On 18 June 1880, age 18 and 9 months, Henry Saword, a clerk, enlisted with the Royal Marines. He was 5’8 with a fresh complexion, grey eyes and light brown hair, and — showing him to be a natural fit for the Navy — a ‘slightly tattooed left forearm’. (I wonder what the tattoo was?) His attestation oath was taken at the Westminster Police Court, and he agreed to serve for 12 years.

However, less than a fortnight later, on 30 June, a letter was sent to Henry’s superiors from his previous employer, C. F. (Charles Frederick) Kell, whose Lithographic Drawing & Printing Offices were at 8 Castle Street Holborn. Unfortunately for Henry, Mr Kell wasn’t writing to wish him well with his military career. He complained that Henry had ‘left my employ abruptly’ and that ‘I am anxious he should complete his work.’ Charles Kell continued, ‘as I know he is seeking his release would you kindly let me know how soon he will be free’.

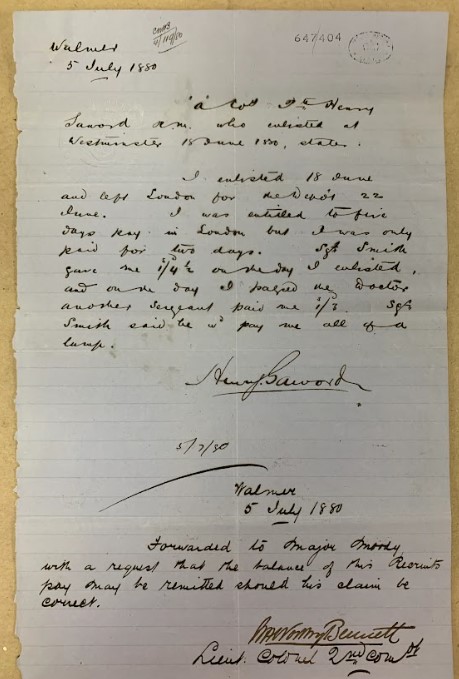

I don’t know if Henry was, as Kell asserted, seeking his release, but he was certainly making sure that he had received every penny owed to him. On 5 July, he wrote to A Company stating that he had only ben paid for two out of five days in London. This was investigated and found to be correct. On 16 July, Henry received the three days’ pay he was owed, and made out a receipt at the Swan & Horse shoe, Gardeners Lane, Westminster, a pub that was used as a recruiting base by the Royal Marines until it closed in 1899.

On 10 July, Henry purchased his discharge at the cost of £10. He had been in the armed forces for just 19 days. Had Henry fallen out with his employer and impulsively enlisted (possibly getting a bit of a tattoo as well), only to return to his employer just three weeks later?

Henry’s record closes with an entry in the ‘Company Defaulters’ Book’. I don’t know if he returned to Kell’s lithographic offices. In the 1881 census, Henry’s occupation was Commercial Traveller. However, in 1891, still living at home with his mother, Henry was a warehouseman — which I believe means he was a wholesaler. Unfortunately I don’t have any records for Henry after 1891. Perhaps he emigrated, or maybe, just maybe, he returned to the Marines, and was able to sharpen his shooting skills once more.

Case 3: Nicholas Ronksley — Discharged

Nicholas, my 5x great grandfather, married Elizabeth Thomas at St Leonard’s, Shoreditch in 1795. Over the next seven years they had five daughters, including my 4x great grandmother Elizabeth Ronksley, all baptised at St Olave’s, Southwark. The parish clerk, who had an elegant hand, consistently included the father’s occupation in the baptism register, showing that in 1796, new father Nicholas was a labourer, but from 1798 to 1806 he worked as a Porter, or more specifically, in 1798, a Wine Porter. Land tax records show that from 1807 until his death in 1816 he rented property at Great Maze Pond, from the governors of Guys Hospital.

Given the location, it’s very likely that he was a hospital porter. Wine was used medicinally in 18th-century hospitals (according to a commercial website, wine was the largest single expense of Leicester Hospital in 1773!). However, newspaper advertisements for hospital porters around this time typically called for a single man who could write well, whereas Nicholas was married, and probably couldn’t write, as he only made his mark in the marriage register (in contrast to Elizabeth, whose signature was neat and clear). Desired ages varied from ‘under 30’ to ‘about 40’ or ‘middle aged’, but more importantly, the job required someone strong and healthy. Whether Nicholas was a healthy young man, I can’t say, but he did not live a long life, dying when his youngest child was only 10. Nevertheless, the role of a hospital porter also required a ‘good character for honesty and sobriety’ and perhaps that is where Nicholas excelled.

Ronksley is an uncommon name, which in this period was confined almost entirely to an area just north of Sheffield. I found no evidence for any other Nicholas Ronksley in London, and the only potential baptism I could find in online databases was in Silkstone, Yorkshire, 1776 — the son of Francis Ronksley of Thurgoland. This potentially made Nicholas my first known Yorkshire ancestor and my first ‘gateway’ ancestor, with a family tree that goes back to Medieval nobility. But how could I prove that my ancestor in London was the same man?

Since he had an uncommon name, I searched for Nicholas in the National Archives Discovery catalogue, which found a very intriguing record: In books containing descriptions of men joining the Royal Horse Artillery (WO 69/1/3117) there was an entry for ‘Nicholas RONKSLEY. Born Throughland [sic], Yorkshire. Enlisted 1794 aged 17 years. Note: Claimed as apprentice 1798.’ I now knew that the Nicholas Ronksley from Thurgoland, b. 1776, had indeed come to London, and that he had joined the army. I also knew that he hadn’t stayed in the military. However, if this was my ancestor, how had he ended up working as a labourer and porter? And how could he have been an apprentice in 1798 when he was already married and employed?

At TNA I was able to examine the RHA record first-hand. Unfortunately, no further details were offered about Nicholas’s apprenticeship, only the words in the last column, ‘Remarks’, ‘Claim’d an Apprentice’ with a date, 16 January, a very faint year (not necessarily 1798) and other unreadable characters.

However, the description revealed that Nicholas’s previous Trade or Calling was ‘Farmer’, and that he had enlisted on 7 May 1794, at what looks like Kendal (though that’s 100 miles northeast of Thurgoland). He’d been mustered on 6 December 1794 in E company so was an early recruit to the RHA, which had been formed in February 1793 to provide mobile fire support to fast-moving cavalry units after Britain declared war on revolutionary France1. His troop had been created at Woolwich on 1 November2.

He was the only farmer on the page, out of 18 men; perhaps with that background, he had significant skills in working with horses. The horses used by the RHA had to be broken and trained to work in teams, harnessed together and pulling a ton and a half of artillery across rough country, under fire.3 He was also one of only two who could read, but not write; this mismatch of skills aroused my curiosity (leading to an interesting discussion on Twitter) but it was also a small piece of evidence that matched him to my ancestor (though admittedly, many labourers would have been unable to write their name).

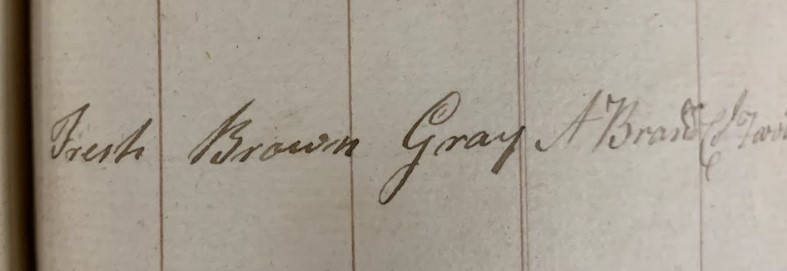

Although I knew that the book contained descriptions, I wasn’t sure how much physical detail would be recorded, so I was thrilled to find out that 17-year-old Nicholas was 5’6 with a fresh complexion, brown hair and grey eyes.

According to the National Army Museum, the RHA was formed in 1793 after Britain declared war on Revolutionary France: ‘Later that year, the Royal Regiment of Artillery created a mounted branch to provide mobile fire support to fast-moving cavalry units. Initially formed of two troops, this new unit was known as the Royal Horse Artillery (RHA).’2 Nicholas may have joined out of patriotism, a sense of adventure, economic reasons, or social expectations. Other researchers have found that he was among the younger of 14 children (I have not verified this). Some of Francis’s sons would have needed to find other trades or occupations, beyond the family farm. However, since the Militia Act of 1757 had created a professional army, it had also become a respectable, even desirable, occupation for a younger son who wouldn’t inherit land.

After examining this document I still could not be sure that Nicholas Ronksley, soldier and apprentice, and Nicholas Ronksley, porter, were one and the same. However, I found two key pieces of supporting evidence for the match elsewhere:

- I was drawn to the PCC wills of George Ronksley, victualler of Chesham, Buckinghamshire (d. 1817) and his wife Elizabeth Ronksley (d. 1822) — because these were other Ronksleys in the south of England, contemporary to mine. Moreover, they had married in London in 1796 … ~

Bingo! Elizabeth bequeathed money to Elizabeth, the widow of her late husband George’s brother, Nicholas Ronksley, and to Nicholas and Elizabeth’s five daughters (all named). So, George and Nicholas were brothers. I then, critically, found a baptism of George Ronksley to Francis, in Silkstone, Yorkshire, 1765. Interestingly, George, more than a decade older than Nicholas, could write his name. Perhaps the family’s budget for education had run out by the time Nicholas was born. - I also have a DNA match that connects me to Francis Ronksley: Francis would be my 6x great grandfather, and the handy Ancestry Thrulines tool only goes back to 5x great grandparents. However, I was able to look at my mum’s Thrulines, which takes me back one more generation, and found that she is a DNA match to a 6th cousin, a descendant of John Ronksley, who was baptised to Francis Ronksley in Silkstone in 1759.

With a high degree of confidence that Nicholas Ronksley from Throughland is indeed my 5x great grandfather, I wondered again about the circumstances of his leaving the RHA. It’s not clear whether he had seen any action overseas, and exactly when he was ‘claimed an apprentice’. That wording perhaps implies that he had absconded — escaping from an apprenticeship in Kendal by enlisting? If his master then caught up with him, showing his commanding officer their apprenticeship bond, he might have been forced to leave his military service. Nicholas might then have secured his freedom (but not his Freedom) before carrying on with his life on his own terms.

Alternatively, did his relationship with Elizabeth necessitate him leaving either the RHA or an apprenticeship? When they married, Nicholas was only about 19, a decade younger than his bride. The baptism entries for their daughters included birth dates, which reveal that their first child, Mary Ann, was born only eight months after the marriage. Did Elizabeth realise she was pregnant, and that she needed to marry her young beau as soon as possible? In these circumstances, he would have had to find work quickly. Since Elizabeth was from Shoreditch, she may have wished to stay close to home rather than go to Yorkshire. And since there was little need for a farmer in the Metropolis, and Nicholas was not fully literate, unskilled labour might have been his only option.

In failing to complete an apprenticeship, Nicholas wasn’t unusual; in 1814, a Parliamentary committee estimated that 70% of London parish apprentices didn’t complete their terms.4 Though Nicholas probably wasn’t a parish (pauper) apprentice, the overall apprenticeship drop-out rate in 17th-century London had been 50%, and these statistics point to it being extremely commonplace.

Despite leaving the RHA, and possibly abandoning an apprenticeship, by the time Nicholas reached full age he attained a respected appointment, which he retained for many years. But sadly, Nicholas Ronksley died before he reached the age of 40, and Elizabeth was left a widow with five young children. Her life can’t have been easy — she died 20 years after her husband, in St Olave’s workhouse.

Richard, Henry and Nicholas share many common threads, but they enlisted at very different times in British history, in different divisions, and thus would have had very different experiences. During Nicholas Ronksley’s service with the Royal Horse Artillery (approx 1794-1798), Britain was at war with France. Richard Maultby deserted the Rifle Brigade in 1831, when British troops were deployed to suppress uprisings of enslaved people in Jamaica, though the Rifle Brigade (95th Regiment) was not involved in that conflict. When Henry Saword joined the Royal Marines in 1880, the British empire had greatly expanded, and its army and navy were fighting in Afghanistan, Egypt and South Africa.

By examining some records of their premature exits from the military I have formed clearer impressions of these fresh-faced young men, all just 17-18 years of age. I hope to look at further sources to learn more about them as individuals as well as the historical context that would have shaped them. Although I will probably never know what drove their decisions to enlist or to leave, there are hints that all three were frustrated by their apprenticeships or jobs, and took a youthful leap at an opportunity to do something more exciting, perhaps even to travel the world. But after enlisting, the reality of military training and service didn’t live up to their expectations, and they were eager to return to the civilian life. I’m grateful that Nicholas and Richard left the army early and started a family, or I might not be here today!

References

- https://www.nam.ac.uk/explore/royal-horse-artillery

- https://www.napoleon-series.org/military-info/organization/Britain/Artillery/RHA.pdf

- https://www.britishempire.co.uk/forces/rha.htm

- My Ancestor was an Apprentice, Stuart A. Raymond (The Society of Genealogists Enterprises Ltd, 2010)