Chances are, you have ancestors who were domestic servants, or who employed domestic servants. Have you taken the time to look at who their employers or servants were, and how the ‘other half’ lived?

Although it may seem that life upstairs and downstairs was very separate, many domestic servants lived and worked at close quarters with the family of the house. The status, lifestyle, and interests of an employer could have had a significant impact on servants, but servants also deserve recognition for their invisible role in wealthier ancestors’ history; their hard graft enabled their employers to enjoy a better quality of life and leave their much more visible legacy.

By including employers and employees, servants and masters/mistresses in your FAN club (Friends, Associates, Neighbours) you might uncover some rich and surprising stories. Here are two from my family tree …

Part 1: Polly Smith and the Gosselins

My great grandmother was named Mary Smith on every official record, but she was known to friends and family as Polly. Polly was born in 1878 in Stoke Mandeville, Bucks, the daughter of an Ag Lab and an ‘Ag Lab’s Wife’. However, changes in farming methods reduced the need for women and girls to work on the land, which presented a challenge to large families. In 1891, at the age of 13, Polly was enumerated in her parents’ home in Stoke Mandeville but was already working as a domestic servant. Her two older brothers, Edwin, 20, and William, 16, worked as wheelwrights. Her older sister, Annie, 19, was a domestic servant in Aylesbury for the family of a banker’s clerk. Only her two little sisters, seven-year old Emma and two-year-old Lizzie, weren’t contributing to the family’s income. (And two, or possibly three, more younger sisters had sadly died). The family of seven lived in four rooms.

Stoke Mandeville parish had a population of under 500, as well as an ebbing number of cholera patients who were treated in an isolation hospital on its border with Aylesbury. After WW2, Stoke Mandeville hospital became world-renowned for treatment of spinal injuries and as the birthplace of the paralympic movement. However, as the Victorian era came to an end this was still a very quiet, rural location. Although Polly had found work, and gained skills, her opportunities in Stoke Mandeville would have been very limited.

By 1901, Polly had left Buckinghamshire behind for Battersea, 40 miles away. In leaving the village of her birth, whether by choice or necessity, she was part of a local and national trend. Stoke Mandeville’s population more than doubled from 1801 to 1871, but since 1871 it had declined by one fifth. From 1891 to 1901, the population of England and Wales grew 12%, but Bucks only grew its population by 1.5% compared with London’s 7%.1 The numbers show plainly that people, including young women like Polly, were leaving the countryside for urban areas. In industrial towns, women found work in factories, but elsewhere, women’s work was dominated by domestic service. In 1891, 1.38 million people in Britain were employed as indoor domestic servants.2

What was it like in London at the turn of the 20th century? The air was full of soot and smoke, and 300,000 horses were creating 1000 tons of dung on the roads every day.3 Battersea, which only 60 years earlier had been much like Stoke Mandeville, still had some green spaces, but was now packed with industrial buildings, railway sheds, and in some areas, slums. Nevertheless, there were plenty of comfortable new homes there for middle class people who could afford the convenience and status of employing a general servant.

In 1901, Polly, aged 22, was employed as a housemaid by the Gosselin family in York Mansions, 132, Prince of Wales Road. The family consisted of Nicholas Gosselin, 63, a ‘Retired Major of Infantry Army Man’ born in Plymouth, his wife Catherine Rebecca ‘Kate’ Gosselin (née Haslett), 57, from Londonderry, Ireland, and their unmarried daughter Selena Frances, 33, also from what’s now Northern Ireland (County Cavan).

The National Archives; Kew, London, England; 1901 England Census; Class: RG13; Piece: 442; Folio: 99; Page: 9 (via Ancestry.co.uk).

York Mansions was constructed in 1897 and completed in 1901, so it was brand new when Polly moved in. The building consisted of 100 flats arranged around courtyards. Flats at the front overlooked Battersea Park. The apartments were purposely designed for a family with a live-in maid, and thanks to Wikipedia I have a detailed description of the layout, including the spaces that Polly would have lived and worked in:

Flats measured approximately 1,500 square feet (140 m2) for a 3-bedroom flat, and 1,800 square feet (170 m2) for a 4-bedroom flat, and included a drawing room, dining room, bathroom and rooms for a maid to live and work. A below-ground corridor ran the full length of the building, which provided internal access to the three separate courtyards and also acted as a servant’s corridor (servants did not use the main entrance to the building). In addition, the building was equipped with service lifts which led directly from the courtyards to the kitchens.

As had become standard, a small servant’s corridor was separated off within each flat and a separate servant’s lavatory (but no bathroom) was provided. Except at the ends of the building where it would have been considered too public and unseemly, the servants’ lavatory was outside, accessed from the balcony beside the kitchen door.

No separate scullery was provided and the original plans show the kitchen sink in the same room as the range and always in front of a window. At the time this was an unconventional arrangement, and was later termed ‘American style’. The flats at the rear corners of the building offered an unusual scenario where the maid, working at the sink, looked out at Battersea Park and had one of the best views in the whole flat.

When built the flats were modern, and had Queen Anne and Kate Greenaway style fire-surrounds, corrugated brass finger plates and plain ceilings. Ceiling roses were still being installed in many new houses but, by this date, were increasingly being viewed as somewhat “lower middle class”. The flats also had a chrome postal handle, some of the York Mansions’ flats still make use of the original fitting (the postal handle is a horizontal post flap with a fixed handle just below the opening, which is used to pull the flat door shut).

Although electricity appears to have been laid along Prince of Wales Drive, London at a very early stage, it was not extended into York Mansions until after the First World War. Lighting was by gas, utilising the new incandescent mantles, which concealed the naked flames and produced a softer, pleasanter light. Cooking was by solid fuel, using the rather square-rather-than-wide kitchen ranges. A coal-bin for each flat was provided in a cupboard outside the kitchen door in the servant’s corridor.4

From this description, I can tell that my great grandmother, though living in a family home, would (probably) have been kept as separate from her employers as possible. And unlike the family, she had no bathroom. Nevertheless, at least she could enjoy the view while she worked at the sink! Thankfully, Polly would not have been completely isolated, as she was not the only servant in the home. There was also a cook — 32-year-old Mary Stoat, from Ireland. Two servants for a family of three may sound very comfortable, but in 1891, the Gosselins had had three live-in servants — a cook, housemaid and parlour maid. Even if their previous home was larger, Polly was doing the work that had previously been done by two women.

A housemaid typically rose by 6 am and worked until late at night. Her responsibilities would have included cleaning and polishing, lighting fires, setting and clearing tables, bedmaking, and needlework.5 Without a parlour maid, she would probably also have answered the front door, attended to guests, and served meals. Although there isn’t room in this blog to go into more detail on domestic service, I can recommend a very evocative book, a day in the life of a Victorian Domestic Servant, by L. Davidoff & R. Hawthorn (George Allen & Unwin Ltd, 1976), which, although set a few decades earlier, really brings their world to life.

As a working-class woman, Polly would probably have known about Battersea’s reputation for political activism. Britain’s first socialist party was founded there by John Burns in the 1880s, and in 1892, Burns became one of the first Independent Labour Party members of Parliament.6

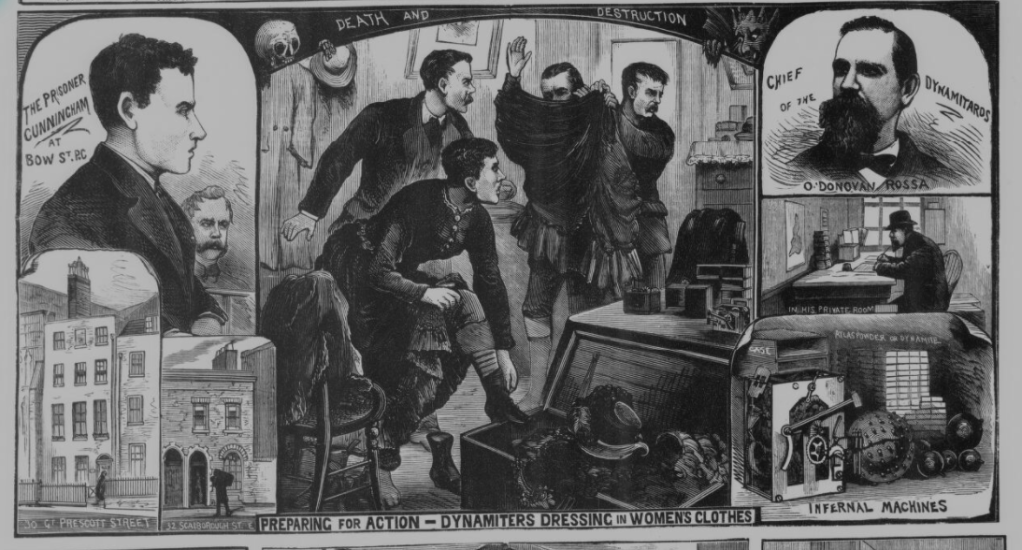

Ironically, Nicholas Gosselin, the head of Polly’s household, had made his career leading efforts to suppress the ‘radical’ political movement for Irish Home Rule. Gosselin, the son of an Irish Army Major, had joined the army at 16. He later served as an Irish magistrate before being head-hunted in 1883 by the Home Office, who put him in charge of the newly formed Special Irish Branch. Their mandate was to gather intelligence on Fenian organisations operating in Glasgow and northern England. The Fenians were a secret political umbrella organisation with members in Ireland and the United States, dedicated to Ireland’s autonomy. Seen as freedom fighters by some, and terrorists to others, between 1881 and 1885, the Fenians launched a series of dynamite attacks on England’s urban centres, terrifying the public. Over 80 people were injured and a young boy was killed.

Gosselin, nicknamed ‘The Gosling’, coordinated covert intelligence agents across Britain and Ireland, and worked closely with Dublin’s Metropolitan Police. Gosselin’s correspondence with Balfour, Chief Secretary for Ireland (and later PM), shows that he had an agent working within the Irish Party, code named ‘L’, whose palm was ‘itching’ for bribes. His papers also reveal that he employed agents provocateurs, including an American ex-Fenian, to seed conspiracies about Fenian dynamite threats. He was also instrumental in bringing down Parnell, head of the Irish Nationalist Party, who, with the support of Liberal leader Gladstone, hoped to achieve Home Rule for Ireland. By exposing more details of Parnell’s long-term affair with his mistress, Gosselin helped stoke the scandal that ultimately stalled Home Rule, removing an option that could have avoided another century of bloodshed. Fenian bombing campaigns continued in England and Ireland until 1900, but in the 1890s Gosselin turned his attention to Irish republican organisations like Clan Na Gael. Athough Gosselin claimed to be simply a retired army man in the 1901 census, he continued to work for Irish Special Branch until his retirement in 1904/5.

I studied the ‘Irish Question’ in A Level History, but that was a long time ago, and this is an extremely complex subject, so I can’t claim to fully understand the role that Gosselin played. However, I’ve included some links to learn more about him below.

I wonder what Polly felt about Major Gosselin. Was he a hero? A man to be feared? Or simply an employer who paid her wages? Did she, in fact, have any contact with the ‘man of the household’, or only with the women of the family? After all, it was the lady or ladies of the house who typically oversaw its management. Unfortunately, I know much less about Kate and Selina Gosselin. Kate was the eldest daughter of William Haslett, a JP and the Mayor of Londonderry, so I imagine that she was a confident and educated woman who had always had servants at her beck and call.

After Nicholas Gosselin retired from special branch, he was knighted, and he and his wife moved to Kent. However, he continued to be politically active. In 1911, Deputy-Lieutenants and magistrates of Co. Monaghan met to discuss their approach to an imminent visit by the new King George V. Sir Gosselin expressed his wish to ‘pour oil on the troubled waters’; ‘they were assembled there to congratulate the king upon his succession to the Throne of this mighty Empire’ and ‘they should stick to that one subject.7 You can watch a newsreel of the royal visit to Ireland in 1911 here. In 1916, Gosselin’s was a prominent (and controversial) voice calling for conscription in Ireland.8 Lord Gosselin passed away in 1917, followed by Lady Gosselin in 1920. Selina never married, and passed away in 1955.

In 1906, Polly Smith married William Wyatt, my great grandfather. William was born two miles from Polly, but had lived and worked in London as an engine driver on the Metropolitan Line, which connected Bucks to central London. They settled in Willesden and raised a family before finally returning to Buckinghamshire. My dad, their grandson, had no idea his grandmother had worked as a domestic servant. Polly’s death certificate gave her occupation as ‘wife of William Wyatt a Retired Railway Engine Driver’.

I’m proud that Polly had the courage to go to London to find work as a young woman, and the strength to carry out such physically demanding work. I now know that Polly also played a role, albeit behind the scenes, in the complex history of Irish independence.

Learn more about Nicholas Gosselin and the Fenians:

- Nicholas Gosselin – Wikipedia

- The Fenian Dynamite Campaign and the Irish American Impetus for Dynamite Terror, 1881-1885

- History Ireland: Keeping the lid on an Irish revolution: the Gosselin–Balfour correspondence

- Papers reveal British government plots to scupper

Further Reading: Christy Campbell, FENIAN FIRE: The British Government Plot to Assassinate Queen Victoria (HarperCollins, 2011)

In Part 2, discover the story of Millicent Gifford and the D’Arcy Ferrars.

- https://www.visionofbritain.org.uk/census/EW1901GEN/4

- https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/magazine-19544309

- https://www.npr.org/2015/03/12/392332431/dirty-old-london-a-history-of-the-victorians-infamous-filth

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/York_Mansions

- http://www.avictorian.com/servants_maids.html

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battersea

- Belfast Telegraph – Wednesday 28 June 1911 (BNA)

- Freeman’s Journal – Tuesday 15 August 1916: Reviving the Conscription Cry (BNA)

I LOVE this story! What an amazing life Polly led – so different to the one she would have known back in Stoke Mandeville. You’ve really painted a picture here, I can almost smell the smoke in the city air!

Such a fascinating family she worked for too. I have so many questions – I wish Polly was here to answer them!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I also really wish I could have asked her questions. Sadly, she died before I was born.

LikeLike

I think this subject of servants and their employers is under-researched and your blog explains why. So many of my rural female ancestors worked in domestic service, some for the whole of their lives. They must have often got to know the families they worked for very well. I imagine that if they kept the same employer, there was a good relationship. Thanks for sharing Polly’s story. It was really interesting to learn about the flat where she worked in Battersea. You can just picture her at the kitchen sink, her hands covered in soap suds, as she admired the view.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I read your blog about courtships afterwards, and so many of the women were in domestic service. I think it must have been hard for servants to find the free time to socialise, but clearly, they managed!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Church must have been a great meeting place!

LikeLiked by 1 person