When you find a child missing from a census, the first assumption is probably that the child has died. Sadly, this was far too often the case. Sometimes though, they were living with other family members. You might even find them with a grandparent living right next door, where there was more space!

Of course, we all visit family now and again, and it’s possible that on the night of the census, a child was just visiting that day, or staying there for a short time. However, it was also quite common for children to be raised by other family members, even when their parents were still living.

This blog post is the first of two stories about women in my family who were each raised by an aunt and uncle. It’s also a reflection on the lives they had, compared with the lives they might have had.

The Mysterious Locket

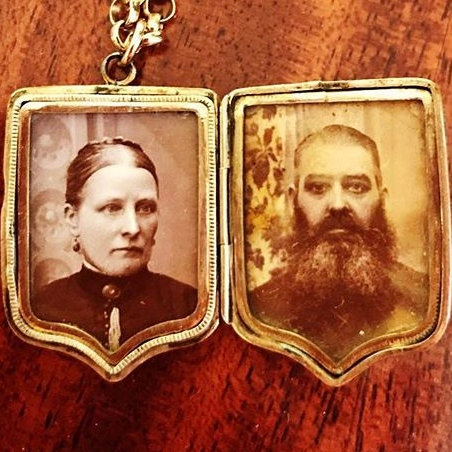

In 2018, my husband’s aunt showed me a locket that had belonged to her grandmother (my husband’s great grandmother), Ida Maud Martin née Gifford. The locket contained striking Victorian photos of a man and woman (which you might recognise from my homepage and social media accounts). She told me that her grandma had been brought up by the couple in the locket, but she had no idea of their names. It was a branch of the family I hadn’t looked into yet and I was thrilled to have a new mystery to solve!

Ida was the daughter of Mark Gifford and Phoebe Morse, who lived in the Forest of Dean. Like many men in the region, Mark Gifford was a coal miner, as was his father, also Mark Gifford. In 1851, when Mark Sr was 61 and Mark Jr was 13, they were both coal miner labourers living in the village of Bream. In 1856, there were 221 pits in the Forest of Dean, and almost every man and boy was a miner. In 1861, both Mark Giffords were still coal miners, even though the older Mark was by then 73. He did eventually leave coal mining … but rather than retiring, he worked as an agricultural labourer into his eighties! Mark Gifford’s brothers also worked as miners of coal and iron ore, except the youngest, who was deaf and dumb.

In 1866, the younger Mark Gifford was in the newspapers, after a woman (in one article called a prostitute) stole a sovereign from him at a ‘low beer-shop’ in Gloucester. Just a few weeks later he married Harriet Ann Jones. Mark and Harriet had two daughters and a son. However, Harriet died in 1874.

The following year, Mark remarried to Phoebe Morse, a miner’s daughter. Two of Phoebe’s brothers had died a few years earlier in mining accidents, which highlights how dangerous this work was. Mark and Phoebe also had two daughters and a son, the first being Ida Maud, born in Yorkley in 1877. In 1881, Mark, then an iron miner, lived with Phoebe and four of his children – the younger two children from his first marriage (the oldest daughter had left home to become a domestic servant) and the younger two from his second marriage. However, four-year old Ida was living 120 miles away with William & Harriet Jones, in Walton on the Hill, just outside Liverpool, where William was the warder of Liverpool Gaol. Ida was described as their niece. And there Ida stayed, until she got married.

Who were William & Harriet Jones? William Jones was born in Ireland in about 1834. Censuses show that he was working as a warder of Liverpool Gaol in 1871, 1881 and 1891. At first I assumed that William was a brother of Mark Gifford’s first wife Harriet Jones. However, the Jones name was a red herring. Censuses show that William’s wife Harriet was born in Yorkley in the Forest of Dean, like Ida. Harriet was in fact born Harriet Morse, and she was an older sister of Phoebe Morse — Ida’s mother. This did indeed make William & Harriet Jones Ida’s uncle and aunt. Unfortunately, I have not found a marriage certificate for William Jones and Harriet Morse or any sign of Harriet in the 1851 or 1861 censuses of England. It seems plausible that they lived in Ireland during this period, and married there before coming to Lancashire in the 1860s.

Lots of questions come to mind:

- How old was Ida when she left home?

- Why was she selected or sent away to be raised by her aunt and uncle? Were her parents struggling for money, or unable to cope with caring for all of their children?

- How did Phoebe feel about her own first child leaving home while she continued to raise two older step-children?

- Why were William & Harriet Jones willing to raise Ida?

- How did Ida feel about growing up without her parents and siblings, and did she ever see them or write to them?

- How did Ida’s life in the suburbs of Liverpool compare with life in the close-knit Forest of Dean mining community?

I don’t know the answers to any of these questions for certain. What I do know is that William and Harriet do not appear to have had any other children of their own. In 1871 they’d had another niece in their household, Harriet Ansley, aged 12. Young Harriet’s full name was Damaris Harriet Bailey Ansley and she was the daughter of Eliza Morse, another sister of Harriet and Phoebe. Eliza had left the Forest of Dean for Liverpool in the 1850s and married Henry Ansley, a porter, and later coachman, who hailed from Canterbury. In 1871 Eliza and Henry Ansley, living in Liverpool, were well-off enough to afford a servant. But given that Harriet was not said to be a visitor in the Jones’s home, it seems likely that her aunt and uncle were helping to raise her, for an unknown reason. By 1881 Harriet Ansley had become a schoolmistress, married a chemist, and moved in with her parents in Walton on the Hill. At the same time, William and Harriet Jones presumably had the desire as well as the means to offer another girl a home and an education.

As for why Mark and Phoebe gave up a child: Ida’s younger brother seems to have been poorly as an older child, so perhaps he was unwell as a baby too, and demanded extra funds and attention. It is hard to understand why Ida was selected to leave, rather than one of her older half-siblings, whose birth mother had died. However, it would not be long until her half-siblings, aged about 7 and 10, would be old enough to work and help to support the family.

I think Ida must have had a much more comfortable and secure childhood with her aunt and uncle than she would have had with her parents. As a prison warder, I assume her uncle would have been better educated and significantly better paid than her collier father, and that her adoptive family would have had higher social status and greater respect than the one she left behind. Additionally, she was the only child in William and Harriet’s household when they took her in, so had the benefit of her aunt and uncle’s undivided attention and resources.

Ida grew up in a community dominated by the prison (built 1855), with most neighbours also being prison warders and their families. A workhouse had also been built there in the 1860s. I wonder how much contact she had with inmates of the prison or the workhouse. In 1889, when she was about 12, Walton Gaol held a ‘celebrity’ prisoner — Mrs Florence Maybrick, an American woman who had been charged with the murder of her husband, a Liverpool cotton merchant. While awaiting trial she spent several days at Walton, where she was said to be ‘lying prostate’ from weakness, and was visited by her mother. Florence was sentenced to death, but was widely believed to have been wrongly convicted, and her sentence was eventually commuted to life imprisonment. After some years in Woking and then Aylesbury prisons, she was released and returned to the United States, where she wrote a memoir of her ‘fifteen lost years‘. In the first chapter she described her time in Walton Gaol, a ‘tall, gloomy building’, where she had been overseen by a female warder. Initially held in a cell with only a bed and chair, and with only bread and milk to eat, she had paid to upgrade her room to one with a washstand, and received her food from a hotel. Although William Jones probably had no direct contact with this female prisoner, I can imagine the family discussing her case over their supper.

In the 1891 census, Ida, still living with her aunt and uncle, was 14, and a dressmaker’s apprentice. The photograph below was taken at about that time, suggesting her aunt and uncle’s pride. Ida stayed home until she was in her twenties. Back in the Forest of Dean, Ida’s sister and half-sisters all left home as teenagers to go into domestic service, and her half-brother became a miner like his father and grandfather. At the age of 19 he was convicted of an attempted assault on a woman, but let off due to previous good behaviour and the ‘great temptation [he] was subjected to’! He continued to be in trouble with the law for violent behaviour; even at age 71, an old-age pensioner, he was charged with stabbing his neighbour with a fork! Her full brother seems to have been unwell as a child, and died at the age of 20.

In 1891, three children aged five to nine, with the surname ‘Day’, were visitors to the Jones household in Walton on the Hill. They were in fact the children of Harriet Ansley — William and Harriet’s niece (and Ida’s cousin) who’d lived with them in 1871. Harriet and her husband John Robert Day, a chemist, lived in Toxteth Park, and they also had a one-year-old. It’s impossible to know how long the children stayed with them. Their parents were fortunate to have live-in help with the baby, in the form of a 12-year-old ‘nurse girl’ (poor child!), but they also had an assistant chemist in the home as well a domestic servant. It might have been too tight a squeeze for all of the children as well.

The domestic servant was in fact Harriet’s cousin Elizabeth Gifford — Ida’s half-sister! Considering that Ida’s sister was working as a domestic servant for her cousin, while Ida was learning to be a dressmaker, in the home of her aunt and uncle, it does seem that Ida was the luckier one. (though another half-sister, Millicent, was employed by the charismatic musician D’Arcy de Ferrars in Cheltenham — which I suspect was quite an entertaining situation! You can read her story here).

The intimate connections between these relations over multiple generations show that William and Harriet Jones supported many extended family with roots in the Forest of Dean, that children in the family seem to have often spent time in the homes of aunts and uncles, and that Ida had many more family members in the Liverpool area than I had expected.

In 1899, Harriet Jones died, and in 1901, Ida, 24, still lived with her widowed retired uncle, working as a housekeeper (probably for him). For a while, she must have wondered why she had trained to be a dressmaker. However, William Jones died later that year, and after his death, Ida became Second Nanny to a wealthy family, the Stacpooles. According to my husband’s aunt, she fell in love with a footman, but his social status was so much higher than hers, that the match was impossible!

However, James Martin, a man who delivered vegetables to the house, did fit the bill. In 1905, Ida married James (here they are together) and they soon had three daughters. Did Ida’s parents, who still lived in the Forest of Dean more than 120 miles away, come to her wedding, I wonder? And did they ever meet their granddaughters?

Thankfully, there were relations closer at hand, and the wedding guests might have included Ida’s cousin and aunt, Harriet Day and Eliza Ansley. Sadly, Harriet had been widowed in 1900, leaving her to care for seven children and her widowed mother. In 1907, after her mother Eliza’s death, she emigrated to Canada.

Ironically, in 1911, Mark and Phoebe Gifford, now in their sixties and retired, had a 16-year old granddaughter living with them, who was a dressmaker’s apprentice. By then, perhaps they themselves were able to offer better opportunities to their granddaughter than she had at home. However, their support of their granddaughter would be short-lived, as Phoebe died in 1912 and Mark in 1913. Mark died intestate with his estate valued at just £25.

A beautiful picture of Phoebe has been handed down to us. Based on the dress style, circa 1860s, this would have been taken before she was married. It’s surprising to me that a miner’s daughter had such a full and fashionable gown, and that the family had the means to take her picture. However, Phoebe’s family were free miners (independent miners) and they seem to have been considerably better off than the Giffords.

Was the portrait a precious possession of Ida’s, which she took with her to her new home? Perhaps. Nevertheless, it is her aunt and uncle, Harriet & William Jones, whose pictures she kept in her locket. I’m so glad our family now knows their names.

Updated 13/9/20 and 8/3/24 with additional family relationships and the story of Mrs Maybrick.

Next: Raised by an Aunt & Uncle Part 2: A Transatlantic Record …

This is such an intriguing story and wonderful that you have the locket. You have raised some important questions concerning motivations and emotions that are not easy to answer. It would be fantastic if you can find out more about William Jones and his wife Harriet as this would at least confirm the connection between the families.

LikeLike

Thanks, Jude. My aunt has the locket but I am glad I was able to take a picture of it. I agree that the motivations will probably never be known, but it is so interesting to consider the possibilities. I’d love to find more out about them and place them firmly in the family tree, but I’m finding it difficult to locate them with confidence before 1871, and I can’t find a marriage. Let me know if you have any suggestions!

LikeLike

What a great story – so much to unravel. I’m also delighted to read about someone else’s ancestors in the Forest of Dean!

LikeLike